Figure 1. The three parts of the larger research project.

Peer-reviewed article

Katrine Heggstad*

Western Norway University of Applied Sciences

Abstract

This article investigates and discusses how a fictional framework can be used as a method for research within the field of drama, and how this approach makes researchers understand the situated moments that are researched. The fictional framework is part of a larger research project which focuses on drama with people living with dementia. The article combines artistic practice-based research with a sensory as well as an auto-ethnographic approach, as the practitioners’ family-relations (as mother and daughter) are explored and reflected upon as integral to the method. The article contributes to knowledge production regarding fictional frame in research and reflects on its significance for work with people experiencing dementia.

Keywords: Fictional frame in research; “not me…not not me”; dementia; next of kin; autobiography

Sammendrag

Denne artikkelen undersøker og diskuterer hvordan fiksjonsrammer kan anvendes som metode i forskning innen dramafeltet, og hvordan denne tilnærmingen bidrar til at forskerne forstår de situerte øyeblikkene som undersøkes. Fiksjonsrammeverket er del av et større forskningsprosjekt som fokuserer på drama med mennesker som lever med demens. Artikkelen kombinerer kunstnerisk, praksisbasert forskning med sanselig så vel som auto-etnografisk tilnærming, der dramapraktikernes familierelasjon (som mor og datter) utforskes og reflekteres over, som en integrert del av metoden. Denne artikkelen bidrar til kunnskapsproduksjon når det gjelder fiksjonsrammer i forskning og reflekterer rundt betydningen av slik forskning når en skal arbeide med mennesker som erfarer demens.

Nøkkelord: Fiksjonsrammer i forskning; «ikke meg; ikke ikke meg»; demens; pårørende; autobiografi

Received: May, 2017; Accepted: November 2017; Published: March, 2018.

*Korrespondanse: Katrine Heggstad, Senter for kunstfag, kultur og kommunikasjon (SEKKK), Fakultet for lærerutdanning, kultur og idrett, HVL, 5063 Bergen. Epost: katrine.heggstad@hvl.no

©2018 K. Heggstad. This is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), allowing third parties to copy and redistribute the material in any medium or format and to remix, transform, and build upon the material for any purpose, even commercially, provided the original work is properly cited and states its license.

Citation: K. Heggstad. ““Imagine if… stepping into someone’s shoes” as a research method”. Journal for Research in Arts and Sports Education, Special Issue: «Å forske med kunsten» Vol. 2, 2018, pp. 123–138. http://dx.doi.org/10.23865/jased.v2.968

“Your imagination, my dear reader, is worth more than you imagine.” Louis Aragon in Kershaw (2011, p. 124)

I am an artist in performance art and drama in education, with twenty years of experience in the field of applied theatre and drama. My practice has focused on process drama, children’s performance and theatre-in-education (TIE). Drama is an aesthetic practice, where form and content are of equal importance, and where emphasis on planning, leading, improvising, interacting, reflecting and performing are all part of developing skills and perspectives for reflective practitioners and educators.

In my research, I use the art form to investigate and gain insight into the field of dementia. In this article, two challenges are addressed: 1) I use ‘imagine if’ to understand how to identify with people living with dementia and to understand experiences of their next of kin; 2) as I collaborate with my colleague, who is also my mother, close family relations makes the fictional situations merge with a sense of real-life.

The article is structured as follows: I will first give a description of the project with impulses from the fields which inform ways of understanding dementia. Then follows a presentation and a discussion of ‘imagine if…’ as a research method in more detail. Finally, I reflect on the examples through an autoethnographic approach.

Rather than analysing medical approaches to dementia, this research seeks to get closer to the emotional feel of dementia through dramatic explorations. In this article, I will explore the method of ‘imagine if’ in order to get a personal and insider’s perspective on this issue.

The aim is to better understand what is at stake in the life situation of people experiencing dementia.

In this article people with dementia are not present with a voice, since I here address an early stage of my research project. The dramatic explorations of the method are being developed together with Kari Mjaaland Heggstad, a colleague and a trained drama practitioner. Heggstad is also my mother. Oscar Tranvåg (2015) states that close family relations are essential for people who live with dementia to feel a sense of dignity, and this research addresses that issue. My decision to work with my mother, was informed by Tranvåg’s emphasis on the emotional element of dementia. This family relationship as mother and daughter gives the research an emotional resonance, as we use drama to explore and reflect upon imagined existential life situations of people experiencing dementia through the roles of a mother and a daughter. Thus, Heggstad has a central role in this research project as a co-practitioner, co-artist and co-researcher. However, she is not a co-author of this article.

Her voice will still be present at times and my reflections are inspired by our collaborative work and our conversations.

I will use the pronoun ‘we’ when I speak about the collaborative work we have explored and ‘I’ when I speak as a researcher. Drama is about exploring through imagination what it means to be human. “Imagine if…” is about exploring how life situations can be felt from the inside, by stepping into the shoes of someone else.

According to the Norwegian national centre Aldring og helse (Aging and health) there is currently no valid estimate of how many people live with dementia, in Norway. Estimates vary from 70 000 to 105 000.1 The number of people developing dementia is said to be increasing in society in line with increased life expectancy. I believe that drama can add something of value in the everyday life of people living with dementia, and the larger research project tests that idea.

My project is in dialogue with theories from the healthcare field, the drama and theatre field, from social science and philosophy and pedagogy. From the healthcare field, important research has been conducted by Tranvåg (2015) and Kjersti Wogn-Henriksen (2012). From the drama/theatre field the impulses are drawn from other arts projects with people living with dementia, and drama and theatre research and theories; as from Helen Nicholson (2005, 2012, 2016) and Richard Schechner (1985). While Baz Kershaw (2011) informs the practiced-based2/artistic research methodology. Norman Denzin (2014) and Sarah Pink (2015) inform the biographical, autobiographical and ethnographic approaches as tools for analysing and reflecting on two examples.

Methodologically, Kershaw suggests that practice-based artistic research should consider research starting with a ‘hunch’ or an intuitive feeling as an alternative to starting with a research question (Kershaw, 2011, p. 113). In practice-based research knowledge is developed in practice and it is through the practice the research question becomes clear. The purpose of this article is to clarify what I am asking. In practice-based research, theory is often not chosen beforehand, but emerges in response to the process. In this article, theoretical perspectives will be presented along the way, as partners in the dialogue that is needed to explore the practice.

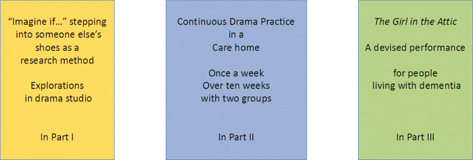

The larger research project will consist of three parts, each of which has artistic practice-based research as a central element. The three parts are shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1. The three parts of the larger research project.

Part I is the focus of this article. I produce data from the exploratory work by writing reflexive logs and then scripting the imagined situations. This can be described as biographical data, as it both contains a description of what has been explored, as well as personal reflections. I also take pictures, make use of props and collect sketches of the practical explorations.

When exploring through practice in part I, I sought to create a space in which emotional responses to dementia can be explored outside the care home, in a drama studio. With my colleague and mother, we created fictional narratives to explore family relations and possible struggles when a relative develops dementia. The aim was to achieve a connection, a direct communication with people living with dementia when moving to part II. The drama studio/rehearsal space became our research laboratory. On the floor, we entered real-life situations and the relationships and narratives that were created and explored in the drama were felt in the present moment. I “imagine if…”, I am a daughter of a person who develops dementia and my colleague a woman who develops dementia.

“Imagine if…” stepping into someone else’s shoes is not based on the observation of the people we work with in care homes, but on a narrative description of how drama practitioner-researchers explored the fictional roles of a person developing dementia and their next of kin. These roles were based on theories and descriptions of dementia from the health and social science fields, like Tranvåg’s focus on dignity in dementia care. Through interviewing 11 persons living with dementia on how they experience the mild to moderate stages of dementia in their daily lives and what they see as important to still feel as equal citizens, Tranvåg finds that close family relations, with husband/wife, children, grandchildren are one of the core elements (Tranvåg, 2015). Wogn-Henriksen’s research gives voice to people developing Alzheimer. How can the communication with health care staff improve? One valuable finding in her research that relates to this project, is the importance of taking the time to slow down the tempo (Wogn-Henriksen, 2012). Audun Myskja’s research examines the potential for learning new things, like new lyrics and songs and finding ways to unlock the musical archive in a person living with dementia (Myskja, 2009). This parallels Ruth Barlett and Deborah O’Connor’s (2010) research. Together they stimulate people with dementia to raise their voice, to act and be part of the discussion. People with dementia are first-hand experts and can share their knowledge and influence the direction in which society develops.

Nicholson offers perspectives on applying drama as a way of co-creating meaning through rituals together with a person living with dementia (Nicholson, 2016). She also offers perspectives on theatre practitioners as archivists, the responsibility of the practitioner when collecting fragmented stories and transforming moments into theatre and storing it in the body as an archive (Nicholson, 2012). Nicola Hatton’s research is an arts-based research practice in a care home with people living with dementia, where she addresses the arts practice as a cultural response to dementia. She develops a theatre practice with a group of people living with dementia and drama students in the project Theatre 20:26 (Hatton, 2014, 2016). Ansley Moorhouse works with theatre and soundscapes with a group in a care home over six months which ends in a performance. She blogs during the process so the people involved can follow the process closely. Another art-project is based on her father’s journey – how he experiences and deals with developing dementia, which she reflects upon in The sound of forgetting (Moorhouse, 2012). Another important researcher and practitioner in the field is Anne Basting. She has developed a storytelling programme project, which is a course for health personnel to help them explore and facilitate imaginative stories with people living with dementia called Time Slips (Basting, 2009). One of her latest arts-projects The Penelope Project, is a long-term theatre and dance project based on Homer’s Odyssey, involving people living in a care home, artists and care workers (Basting, Towey and Rose, 2016). These projects and more are part of our mapping of the field, see Heggstad & Heggstad, 2017.

Our insight into dementia and how it is to live with dementia also comes from other art forms expressing lives of people with dementia in diaries, non-fiction novels, documentary films and screen plays. Two books that have given new insight into the preparatory phase are A demented person’s diary (Wyller, 2013; my translation from Norwegian) and Mother’s gifts (Enger, 2014; my translation from Norwegian). These two books provide important perspectives, one from the person living with dementia and the other from the viewpoint of a next of kin.

Denzin offers methods to write and reflect through the researcher’s self-reflection by writing narratives in his Interpretive Autoethnography (Denzin, 2014)3. I am using the term autoethnographic approach as a blurred genre, a combination of autobiographic and ethnographic study. “[I]t is setting a scene, telling a story, weaving intricate connections between life and art… making a text present …/…/ believing that words matter /…/ (Jones in Denzin, 2014, p.20).

Pink adds another perspective, in emphasising awareness of the senses as an important part of experiencing place and space. Participatory observations can involve a focus on sound, smell, taste, touch… Doing Sensory Ethnography (Pink, 2015).

A research article by Dennis Greenwood (2015) inspired the development of using “Imagine if …” as research method in this project. Greenwood has an interest in drama and theatre, and describes how he has made use of professional actors in his teaching of students/health care staff. The actors act out scenes that show situations where care staff and residents are involved, and where the care staff is either overworked, under a tight time schedule, exhausted or for some reason does not pick up on the needs of the resident (Greenwood, 2015, pp. 225-236). Greenwood uses this method for the students and staff to learn to see, notice and feel the complexity of their meetings with residents. How could this method be transformed in to a research method seeking to prepare for meeting people with dementia? In our first meeting in a care home, we ended up losing our three participants before we had even arrived in the care home (one had moved back home, one had moved to another institution and the third had not returned from his weekend with the family). We initiated conversations and sensuous communication with other residents, hoping to connect and maybe get future participants to the research project. It felt challenging, and exciting to connect. However, the conversation and the communication came to an end when we handed them an invitation letter to this research project.

As we turned back in to the drama studio, we hoped to bodily and emotionally get a deeper understanding of how everyday life situations could be like for people living with dementia and next of kin. Also, we imagined this might help us to stand a better chance of showing respect for the life situation of the people with dementia. Together we created a scenario consisting of a space (room) and a situation – but without a plot. The main prop was a chair. We decided where the entrance to the room was. Situations were then being explored several times through improvisation and enactment. It has furthered developed into scenes: Alone at home, Phone calls, She (Ella) cannot live alone, Let’s visit a nice place, Living in a care home and Role reversal.

Imagine… a pair of deep red woollen slippers with black rubber shoe line is placed on the floor in front of you. When you are ready to take on a role, you slip your feet into the shoes or slippers of a person called Ella. You are now to walk in the shoes of Ella.

Imagine you are around 80 years old and live alone in your apartment. You have started forgetting more than you used to. It annoys you and it worries you. Sit down in your armchair and pick up your hand bag from the floor. You look in the bag. You don’t know what you are looking for. You take out your knitting. You like to knit, but when you are about to start knitting you don’t know how to. It is as if your hands don’t know how to knit anymore. On a set table, next to your armchair there is a notebook and a pen and a telephone. You pick up the book. In this book, you write things down to help you remember. You feel alone. It is as if nobody comes to see you anymore. You can’t remember the last time you had someone visiting. You have written down the telephone number of your daughter. You pick up the phone and dial her number…

My colleague enters the role of Ella, while I enter the role of Ella’s daughter who gets phone-calls, at work, at the grocery shop, at parent-teacher meetings at school, at home. When writing the narrative above I imagine slipping into the slippers of Ella. To imagine walking in her shoes for a moment, stimulated my imagination. I walk into the kitchen – and notice the light coming through the kitchen window. I see the bedroom. The bed is nicely made with two small crocheted pillows. The bathroom. The old toilet doll on the shelf…

Earlier, when my colleague and I have explored this situation, I have not been able to imagine the whole flat. What has been important then, is how my colleague explores the role and situation. When allowing myself to enter in the role of Ella, I see her home from the inside. And when reflecting through writing I am aware of bringing in images from my own home, my grandmother’s home and my colleague’s development of Ella. The imagined shoes/slippers could be an actor’s starting point. The actor must allow herself to try different approaches to the role and the situation. Physically it could be testing out different shoes/slippers, to see what could be useful and fit the character. How does this fictional person take on the shoes? How does she walk in these shoes? How does she sit down? How does she talk?

The actor in the theatre, as here the drama researchers, may investigate the field of how elderly people who have developed a mild stage of dementia act and react. Props and costumes are useful tangible items that might help the actor work from the outside in. Later the chosen props and costumes will be subject to another reading when an audience sees and makes meaning of the way characters, props and story give resonance to the world. The theatre director Constantin (Stanislavski 1993, pp. 46-71) used “the magic if” when describing the possibilities of imagination for the actor.

She has become more strongly affected by dementia. She is now residing in a care home. She talks less. She has a blurred kind of gaze, as if she doesn’t recognise where she is or who is there with her. I knock on the door and enter her room. I stand by the door and look at her. She sits in her big armchair. It looks like she is asleep. I walk over, bend down, and give her a hug.

| I: | Hi mom. She turns her head slightly towards me, and looks at me. She smiles carefully. |

| I: | Were you taking a nap? She lifts her shoulders slightly and smiles a little. She looks out with no clear focus. |

| I: | Look at what I brought today. I bend down and put my left hand into the bag I am holding in my right hand. From the bag, I pull out a quilted, bluish flowered nylon bag. I place it in her lap. She looks down into her lap, and starts stroking over the bag with her right arm. Then she brings it up to her face. She smells it and close her eyes. |

| SHE: | Lovely! She opens the nylon bag and pulls out a morning gown of the same material, only not quilted. She holds it up and looks at it. |

| SHE: | I bought it at Møller. I paid 34 kroners for it! We were going to …. a wedding in Copenhagen. She hesitates a little. |

| I: | Nils Gustav? She looks at me, and gives a slight head shake. |

| SHE: | I don’t remember. |

| I: | Try it on! She struggles to get up, while I help her. She is standing on the floor, waiting. Then she gets the morning gown on. She is confused. |

| SHE: | Where is the belt? There was a belt. |

| I: | I don’t know. I’ll have a look, and see if I find it. |

| SHE: | Look! (laughs) It was long! She bends over and points all the way down to her ankle. She carefully sits down and finds her right position in the chair. |

| SHE: | And then it became very modern with short… I cut it off… and… sewed it up. Hahaha… Look! She laughs and points at a bumpy seem. |

| SHE: | I sewed it up, on my old Singer. Hahaha. Look! I can spot some of the bygone, energy and sparkle that she used to have so much of. It is beautiful and, also delivers a pang of sorrow. I laugh a little together with her. |

The text above is a scripted scene as a thick description. Clifford Geertz described the concept of thick descriptions from an anthropological perspective in 1973. Here, it is based on original notes from the log I wrote down after having explored the scene. I wrote it as a script. It was quite stripped down, in one sense, containing only details of the ‘I’s lines and actions, while the lines and actions of SHE was more limited. My colleague was then e-mailed the draft and was asked to see if her lines and actions ran true with her, and if she could add what was missing and rewrite what needed editing. The text became richer. However, the thickness of this description is not yet full. The question is whether it is possible to transfer the concept to an interpretation of situations, where I am taking part myself – or not. It can also be read as a double ontology of the moment – a hovering between ‘me’ and ‘not me’ and ‘not not me’ in Schechner’s terms. He writes:

During workshop-rehearsals performers play with words, things, and actions, some of which are “me” and some of which are “not me”. By the end of the process “the dance goes into the body”. So, Oliver is not Hamlet, but he is also not not Hamlet. The reverse is also true: in this production of the play, Hamlet is not Oliver but he is also not not Oliver. Within this field or frame of double negativity choice and virtuality remain activated. (Schechner, 1985, p. 110)

The choice of “I” as the role of the daughter/next of kin is the writer (I) retelling the improvised scene. It can also be analysed as an example of how ‘I as a daughter’ and ‘I as the role of the daughter’ in this situation has merged, while I have given my colleague a third person pronoun. I did not call her Ella, since we did not focus on the names of the roles here, it was more about exploring a stage of dementia which was severe. Denzin writes:

This is what autobiographies and biographies are all about: writers make biographical claims about their ability to make biographical and autobiographical statements about themselves and others. In this way, the personal pronouns take on semantic and not just syntactic and semiological meanings. (Denzin, 2014, p. 11 referring to Ricoeur, 1975, p. 256)

The semantic meaning of the use of I and SHE in the scripted text creates a gap between the actors and the script. When my colleague plays the I’s mother, she could have been called MOTHER. Instead I have written SHE. In this way, I create a distance. SHE is not merged with my own mother, still it is based on my mother’s action in role as a mother with a severe stage of dementia. The distance might have been created for my own sake; my real mother does not have dementia. SHE is acting, and it feels real and distant at the same time. SHE is in role, and SHE is the role or with Schechner’s words; my mother is SHE, she is not SHE but she is also not not SHE. The closeness in the imagined situation when it is explored becomes too close for me. It is real. As a reflective researcher, I here take a step back; I distance myself in the description of my mother playing a woman living with dementia. The estrangement of the situation for me as next of kin is close to how next of kin can describe the loss of their loved ones as a stage of sorrow and mourning. I feel the sorrow and I feel the need to observe and analyse her signs of responses and take one step at a time. Slowly.

The self and its signifiers thus take on a double existence in the biographical text. First, they point inward to the text itself, where they are arranged within a system of autobiographical narrative. Second, they point outward to this life that has been led by this writer or this subject. In performativity action turns back on itself and the actor sees double. (Denzin, 2014, p. 11)

The double existence which Denzin describes can be transformed to the double existence in the performance when acting the situation both as the daughter of a person who has developed dementia and being the daughter of the woman who acts the person living with dementia. On another level, I feel the responsibility to represent the felt dilemmas of a next of kin. It is also as if I fear a ghost of the future.

The auto-ethnographic approach is useful as a method in the way it opens up the material, and gives way to describe and explore situations again through a rewriting or rescripting of explored situations. As a researcher, I see something new in the material. I become aware of how the near relationship to my mother-artist and -researcher also gives an extra personal dimension, a deeper understanding of the field/the community we are approaching. I feel more related to the existential life situations, and still humble. By exploring through “Imagine if…” the uncertainty when entering the care home is not so frightening.

The scripted narrative reflects a structured, improvised situation in research through and with drama. The text can be an example of an auto-ethnographic text that is merged with a drama praxis. When I write the situation down I try to stay as close as I can to what I can recall from what happened, but when I share it with my co-researcher, there are elements that are not in the texts, especially the details of her actions. For example, in my first draft, after “Hi mom”, I have written She smiles. By thickening the description, the situation becomes richer: She lifts her shoulders slightly and smiles a little. She looks out with no clear focus. As I revisit the first draft it seems rushed, while the edited thickened description contains a feel of the slow tempo of the situation. I remember trying to keep the biographical text quite stripped. For instance, there are no detailed description before the script starts. It only says: New situation. She has become more demented. The narrative description or stage direction is now much more descriptive. When my colleague and I send the script between us it becomes what could be called a duo-ethnographic script. As my colleague adds some details, I start to remember more details. The collaboration enriches the scripted narrative. In my first writing, I am too focused on my actions and reactions. I miss out on some of her lines and reactions and can only see myself clearly, and I am quite certain of my actions. Still some of it is probably forgotten. Denzin describes an unclear distinction between the fictional and real in autobiographical and biographical texts in this way:

The dividing line between fact and fiction thus becomes blurred in the autobiographical and biographical text, for if an author can make up facts about his or her life, who is to know what is true and what is false? The point is, however, as Sartre notes, that if an author thinks something existed and believes in its existence, its effects are real. Since all writing is fictional, made up out of things that could have happened or did happen, it is necessary to do away with the distinction between fact and fiction. (Denzin, 2014, p. 31)

I experienced “Living in a care home” more emotionally than earlier explorations (as in example 1) where the woman was having a milder form of dementia and had not arrived at a care home. At that stage, the situation was more fictionally framed. The situation was still experienced emotionally, but more in the sense that we both got a deeper understanding of how it can be like for the ones who experience these everyday situations where the cognitive decline affects the families. We explore in roles, but the relation is the same, and in a way, it is not only a way of preparing for the actual work in a care home with people who live with dementia, it is also a preparation for potential future experiences and it is somewhat sorrowful for me. As Nicholson (2005, p. 67) writes “…in non-therapeutic settings sometimes the narrative is taken in unexpected directions by the participants, and this may touch or invoke particular feelings for individual members…”. There isn’t a clear distance. The fictional situation feels real. This knowledge becomes clear to me through practice.

For my colleague, it was different. When in role, she started remembering real-life situations that came back to her. She used a mix of stories from her mother, from relatives and friends who have had dementia, and from her youth. An important element that was prepared before exploring this scene was for the daughter-role to bring a piece of clothing that might be recognisable for the person with dementia-role. The chosen prop was a surprise for my colleague to give the exploration a realness. David Davis (2014) writes: “Enactment needs to resonate the chosen concerns of the play, not the individual actors” (p. 147). Even if this is not a play the concern here is to explore to understand the feel of this kind of life-situation, bringing in things, belongings that can recall memories, stimulate the imagination and maybe also give some security (Pearce, 1998 in Hochey, Penhale and Sibley, 2007).

The object had a smell that reminded my mother of my grandmother. The smell had reference to a different time. It had a mix of smells of the house where she used to live, the scents of make-up powder and a touch of her eau de cologne. These smells in combination with the feel of the texture, the shape of object, its pattern and colours of the material also brought back memories from a different time while exploring being given the morning gown as a surprise in the improvised moment. In Doing sensory ethnography Pink (2015, p. 101) writes: “…[F]or the sensory ethnographer it is important to attend to the meanings of tastes, smells and textures and the significance of their presence.” When relating to the senses the object becomes more than an object. It represents both smells of my mother’s mother and the house they lived in, it also represents the smells I recall of my memories of my grandmother and her house – also through the sensuous description my memory brings pictures of her, that are a mix of photographs and remembered situations. The meaning of this object was both related to here and now in the fictional moment, and to one’s own and other’s memories. The description of the smell is how I remember her description, but when writing the described smells merge with my memories of my grandmother’s smells.

The nearness and awareness of each other, the playfulness, becomes more seriously valuable, as we are in a real mother-daughter relation while at the same time exploring a fictive mother-daughter relation. By playing out an imagined life-situation where the roles are shifted due to what is at stake, this takes us close to real-life situations. Family and close relations are crucial for people who develop dementia (Tranvåg, 2015). In this perspective, our mother-daughter relation gives an extra dynamic to the project. It is not the first time we have worked together – but it is the only time the relation itself is reflected upon. Also, knowing each other so well, makes the estrangement when the illness creeps in, so unreal in real-life, but still as if it happens for real. Everything is to happen at a much slower pace – to be able to find the next step. This mirrors the need for a slow pace in the community of a care home. One cannot rush situations, because the “psycho-motoric pace is weakened with dementia” (Wogn-Henriksen, 2012, p. 86; my translation from Norwegian). To connect with the person living with dementia Kjersti Wogn-Henriksen suggests that we slow down and adjust to the person you are going to connect with, both in the actions and in the pace of conversation. In her research, Wogn-Henriksen has interviewed 7 people developing and living with Alzheimer over a three and a half year-period. She finds that people living with dementia are much like people in general. They seek meaning in life, they are fully individuals who adjust differently. She also addresses humour, and living well with dementia. Challenges on autonomy derives especially when the illness develops to a more constant need of help in daily routines (Wogn-Henriksen, 2012, p. 7).

The mother-daughter relationship is a way to enter the emotional spectre of the life situation of a person who develops dementia and her/his next of kin: It is a dramatic exploration that offers an opportunity to take on roles as somebody else to see something new.

As a researcher from drama and applied theatre the exploration through stepping into the shoes of someone else is also a preparation to enter a community. In part 1 of this research project, we have explored through imagination the emotional spectra of these situations. The scenes have also further developed into a performance lecture/paper which has been presented for colleagues, next of kin and researchers in the drama field. The performance lecture/paper contains some chosen scenes. After each scene, the actors share their reflections on the explored scene. The dramaturgy has a flexible form, to facilitate the needs and responses of that particular audience.

A mother and daughter playing a mother and daughter facing some challenging situations and sharing our emotional reflections seem to open a space for sharing personal stories and together discuss what to do in the specific situation of the scene and, other challenging situations in the next of kin encounter.

When entering a community where memory loss is part of the participant’s everyday situation, the researcher and the practitioner can benefit from exploring the participants’ life situation by entering a role; by stepping into their shoes. It is not a way to empathise with them, but more about identifying with the feelings from the inside of the situation. People living with dementia are not all about memory loss. They also remember. They also have abilities that can be discovered or rediscovered through memory triggers. There is a need for focusing more on how development and growth can occur. “[C]ognition only defines one aspect of the person’s experience” (Barlett and O’Connor, 2010, p. 75).

If the researcher participates and experiences from the inside, as my approach in this article, to what extent is the researcher able to observe? In my attempt to make a script from a log of an explored scene, I become aware of my restricted lenses. I turn the lenses inwards and miss details of the actions and reactions of SHE. But through adding and editing, together with my colleague, the description is somewhat thickened, and taking turns on this one-and-a-half-page script, makes it possible to replay the situation and comment on the details as they appear.

The scripting of the scene, the thickening of the descriptions and the new reflections that come through writing offers deeper reflections and yet another way of thinking about developing the scenes further into a performance-presentation for next of kin and for researchers in the field. What started as a way into understanding some perspectives of how it can feel to have dementia and to be next of kin seems to have a potential to open a space for discussion and sharing. As we share the scenes and our reflections and some meta reflections the audience become part of the story, and develops it further. It develops into a spontaneous sharing of personal stories. This is similar to what Denzin writes:

[S]torytelling is a performative self-act carried out before a group of listeners. The self and personal-experience story is a story for – a group. It is a group story.

But more is involved. As Bill speaks, he throws his story out to the audience who hears it. This audience becomes part of the story that is told… A group self is formed, a self-lodged and located in the performative occasion of the open meeting. (Denzin, 2014, p. 55)

The intention was to share scenes and some reflections and facilitate some form of interaction. Unexpectedly, there was a need for sharing among quite a lot of people: many people wanted to share their stories. So, what was scheduled to be a sharing of four scenes/situations had to be reduced to two scenes, due to lack of time. We slowed down, allowed questions to linger: What happens next? What does the character in role as next of kin do if she cannot make a visit to her mother when the mother needs her to? How do you cope when your parent cannot live alone and there are no available places in care homes in the area where she lives?

Our sharing of stories differs from Denzin’s example. His group develops what he calls a group story. A critical side to the sharing of this project, is that we as artists tell the story of imagining being in the situation while some of the participants are actually living in this kind of life-situation. Imagine if … as a research method demands high ethics regarding the fact that the situations played out are not imaginative for next of kin. They are real.

When collaborating closely with my colleague, focusing on the personal element in this research process I am crossing a line. Is it ethically acceptable? Is this acceptable for the research field? Another question that needs to be asked is whether it is ethically acceptable to write this article in my name only. I can confirm I have done so, but the artistic work – that this article builds on in dialogue with practice-based research – makes this a critical point of the research. Sometimes I am uncertain if the reflections are my own, or if I have adopted it from my colleague and others. Research is a relational practice. It builds on, interacts with, discusses with and challenges other thinkers in the field. Still, writing this article in my name only, clearly positions the responsibility as researcher on me.

From employing an artistic practice-based research methodology of “imagine if…” I have arrived at this research question: How can the development of fictional frame work as a research method in combination with an auto-ethnographic approach, help drama practitioner-researchers in preparing for working with people with dementia? Through the practice-based research together with the writing of this article, I have both arrived at this research question at the same time as I have sought to answer it.

As I started out this work my pre-understanding was that there is a need for a more personal and inside/in-situation perspective in drama research, when working with people who live with dementia. I have worked based on this pre-understanding through developing and exploring the practice-based method “Imagine if… stepping into someone’s shoes”, and in this article I have described and in writing investigated two examples of in-fiction narratives, before reflecting on the examples and analysing them in dialogue with relevant literature. This has been possible through using auto-biographical (Denzin, 2014) and sensory ethnographic (Pink, 2015) approaches. These methods have to some extent a distancing effect – it gives me as researcher an opportunity to step back or to the side for a minute – to discover a new language – a more personal one, to describe and understand the discoveries made in practice. “Imagine if… stepping into the shoes of… as a research method” is a contribution to the discussion of different research methods in practice-based research – and here, in drama and applied theatre research, more specifically. Fictional frame as a research method also opens a door to what drama and applied theatre can contribute with to a larger research field. I attempt to research one essence of drama – fictionalization – from an inside perspective: to take on a role, to step into someone’s shoes for a moment or more precisely to be in the situation, in the moment. Fiction, reality and in this case, auto-ethnography becomes blurred, where the researcher’s experiences and reflections from within become personal and emotional. This touches the borderlines of drama – the distinction between imagined situations and roles has merged.

What is to be learnt from this research project? It is not about legitimizing the effects of the work, but rather to describe and share reflections that can open for new questions. Bjørn Rasmussen (2010) suggests drama researchers build a research design based on the way the artist and the drama pedagogue work in the field; to explore through form and drama conventions to create meaning. This research project lends itself to this suggestion.

What has become clear through the explorations of “imagine if” is that first it gives practitioner-researchers an opportunity to explore, examine, and discuss the emotions of what can be challenging life situations. This gives a sensory way into the care home. In the care home, we explore other imagined situations that stimulate the imagination of the here and now, and sometimes it can trigger memory of younger years.

This research approach still leaves some gaps. My reflections are sometimes blurred with my colleagues’ reflections. Therefore, I will not claim that all ideas and reflections are solemnly mine, but rather that the article builds on the practice we have explored together. She is my mother. She is my colleague. How can our explorations have relevance for other researchers and practitioners in the field? The personal and inside-perspective has been challenging on the emotional level. What started as a “fun” idea, mother and daughter acting mother and daughter became valuable on several levels. First, it gave an insight to the existential life situations, which was a valuable way of tuning in on the social and cultural arena of a care home, which is Part II of the research project: the practice of continuous drama in a care home.

Second, when using a combination of dramatic exploration, biographical and auto-ethnographic approaches gave another way of reflecting and revisiting the explored situations. It also added new meaning. Third, the thickened description helped develop the performance lecture further, which again opened a room for sharing and discussing situations of people with dementia and next of kin. Maybe this method can be meaningful to other researchers who are entering new arenas, and also have relevance to practitioners and students in health care education.

Katrine Heggstad is a PhD candidate at Western Norway University of Applied Sciences, enrolled in the PhD programme Bildung and didactical practices since April 2016 with the project: Drama, Dementia & Dignity: Questioning borderlines in drama didactics. She is also a practitioner and a lecturer in drama and theatre at Western Norway University of Applied Sciences. Over the years she has had a special interest in developing workshops and workshop materials to open up texts, stories to access meaning as young audience, through the approach developing from- text-to-theatre workshops, often in collaboration with Heggstad and Eriksson and Den Nationale Scene. She has held lectures and workshops internationally. Katrine.Heggstad@hvl.no

Kari Mjaaland Heggstad is Professor Emerita at Western Norway University of Applied Sciences. She is an experienced researcher and practitioner in educational drama and applied theatre and has published and presented research and practice, nationally and internationally. Kari.Heggstad@hvl.no

Barlett, R. & O’Connor, D. (2010). Broadening the Dementia Debate. Towards social citizenship. Bristol: The Policy Press.

Basting, A. D. (2009). Forget memory: Creating Better Lives for People with Dementia. Baltimore: John Hopkins University Press.

Basting, A. D., Towey M. & Rose, E. (2016). (Eds.) The Penelope project. An Arts-Based Project to Change Elder Care. Iowa city: University of Iowa Press.

Davis, D. (2014). Imagining the real. Towards a new theory of drama in education. London: Institute of Education Press, University of London.

Denzin, N. K. (2014). Interpretive Autoethnography. (2nd ed.). Los Angeles: SAGE publications Inc.

Enger, C. (2014). Mors gaver. [Mother’s gifts]. Oslo: Gyldendal.

Geertz, C. (1973). The interpretations of cultures. Selected Essays. New York: Basic books.

Greenwood, D. (2015). Using a drama-based education programme to develop a ‘relational’ approach to care for those working with people living with dementia. RiDE: The Journal of Applied Theatre and Performance, Vol. 20. (No. 2), 235-236.

Hatton, N. (2014). Re-imagining the care home: A spatially responsive approach to arts practice with older people in residence care. RiDE: The Journal of Applied Theatre and Performance, Vol.19 (No.4), 355-365.

Hatton, N. (2016). A Cultural response to dementia: Participatory arts in care homes. (Doctoral thesis). Egham: University of London

Heggstad, K. & Heggstad, K. M. (2017). Tilstede – om demens, reminisens og langsomme dramaprosesser. In K. M. Heggstad, B. Rasmussen & R. G. Gjærum (Eds.), Drama, teater og demokrati. Antologi II. I kultur og samfunn (pp. 167-182). Bergen: Fagbokforlaget.

Hockey, J. Penhale, B. and Sibley, D. (2005). Environments of memory. Home space, later life and grief. In J. Davidson, L. Bondi and M. Smith (Eds), Emotional Geographies (pp. 135-146). Aldershot: Ashgate.

Kershaw, B. (2011). Practice as research through performance. In H. Smith & R. T. Dean (Eds), Practice-led Research, Research-led Practice in the Creative Arts (pp.104-125). Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press.

Moorhouse, A. (2012). An Artist’s Statement, The Sounds of Forgetting: An Aural Exploration of Memory and Perception. Occasion: Interdisciplinary Studies in the Humanities, Vol 4, 1-5. http://occasion.stanford.edu/node/101 (accessed 10.02.2018)

Myskja, A. (2009). Musikk som terapi i demensomsorg og psykisk helsearbeid med eldre. Tidsskrift for psykisk helsearbeid, Vol.6. (No 2), 149-158.

Nicholson, H. (2005). Applied drama – the gift of theatre. Hampshire/New York: Palgrave Macmillan.

Nicholson, H. (2012). The performance of Memory: Drama, Reminiscence and Autobiography. NJ: Drama Australia Journal, Vol. 36 (No. 1), 62-74.

Nicholson, H. (2016). A good day out. Applied theatre, relationality and participation. In J. Hughes & H. Nicholson (Eds.), Critical Perspectives on Applied Theatre (pp. 248-268). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Pink, S. (2015). Doing sensory ethnography (2nd ed.). London: SAGE Publications.

Rasmussen, B. (2010). The art of knowing: building a house in no man’s land. In A.L. Østern, M. Björkgren & B. Snickars-von Wright (Eds.), Drama in three movements. A Ulyssean encounter (pp. 75-79). Vasa: Åbo Akademi University.

Schechner, R. (1985). Between theater and anthropology. Philadelphia: The Pennsylvania University Press.

Stanislavski, C. (1993). An Actor prepares. New York: Methuen.

Tranvåg, O. (2015). Dignity-preserving care for persons living with dementia (Doctoral thesis). Bergen: University of Bergen.

Wogn-Henriksen, K. (2012). “Du må… skape deg et liv”. En kvalitativ studie om å oppleve og leve med demens basert på intervjuer med en gruppe personer med tidlig debuterende Alzheimers sykdom (Doktoravhandling). Trondheim: NTNU Norwegian University of Science and Technology.

Wyller, T. (2013). En dements dagbok [A demented person’s diary]. Oslo: Vidarforlag.

1Therefore, there is an ongoing statistical investigation in Trøndelag county in Norway, with 120 000 participants. This might give a more valid estimate. The report will be completed in 2020. https://www.aldringoghelse.no/alle-artikler/vet-ikke-hvor-mange-som-har-demens-i-norge/ (accessed 21.11.2017).

2I have chosen to use the term practice-based, because the practice is where ways of understanding are being explored through fictional frames, reflections are shared and written as logs. Then the data is transformed into scripted texts and narratives to be further analysed through autobiographical and auto-ethnographical approaches.

3The book is a new edition of Denzin Interpretative Biography from 1989.