Introduction

Newly graduated teachers are expected to perform just as professionally as their more experienced colleagues (Caspersen & Raaen, 2014; Cochran-Smith, 2005; Ibrahim, 2012; Tait, 2008); however, many physical education (PE) teachers do not perceive themselves to be fully qualified for all of the tasks they are required to perform (Ibrahim, 2012; Ní Chróinín et al., 2018). PE plays a central role in schooling in many countries, and it is generally valued by students (Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development [OECD], 2019a). Nevertheless, concerns have been raised about the lack of qualified PE teachers and the fact that PE teachers tend to leave the profession after just a few years (Mäkelä et al., 2014; Moen, 2011; OECD, 2019b). Organisational socialisation and professional qualification entail an ongoing learning process that develops both through education and throughout a teacher’s professional career (Lawson, 1983; Schempp & Graver, 1992). In addition, it takes time to adjust from being a student PE teacher to being an experienced PE teacher as well as to develop one’s professionalism and professional practice throughout one’s professional life (Templin et al., 2017, p. 12).

In recent years, concern has also been raised that the lack of PE teachers leaves schools unable to carry out planned teaching activities (OECD, 2019a). To address this concern, various policy initiatives have focused on the design and implementation of induction and mentoring programmes for newly qualified PE teachers. For instance, in the Norwegian context, a recent white paper proposes a guided introduction year for all teachers (NOU 2022: 13). The purpose of these policy initiatives and programmes is to ensure the provision of guidance concerning the transition from teacher education to professional practice, thereby raising awareness of the value of recent graduates’ competence, motivation and desire to remain in the teaching profession.

A characteristic feature of policymaking regarding the teaching profession is the fact that established and new demands exist side by side (Thue, 2017). In this regard, the policy demands facing teachers and the standards required for learning have both changed from teaching students fundamental skills to preparing them for higher-order thinking and performance-based skills (Darling-Hammond, 2006; OECD, 2018). Moreover, teachers have to deal with a diverse and complex clientele, and they must do so in an environment characterised by increasing moral uncertainty, where many methods of approach are possible and where a growing number of social groups exert an influence and have a say (Hargreaves, 2000).

Research on teachers’ induction phase—that is, the transition from teacher education to professional practice—suggests that professional qualification entails an ongoing learning process that unfolds both through education and throughout a teacher’s professional career (Darling-Hammond, 2017; Day & Sachs, 2004; Feiman-Nemser, 2001a, 2001b; Ibrahim, 2012; Ingersoll & Collins, 2018; McDiarmid & Clevenger-Bright, 2008; Smeby & Mausethagen, 2017). However, it appears that the policy demands facing teachers and the standards now required for learning might drive teachers to leave the profession within the first five years of their professional practice (Ingersoll, 2003a; Mäkelä et al., 2014).

In light of the above, the aim of this scoping review is examine previously published research on newly graduated PE teachers in an effort to describe the scope and types of the empirical studies, perspectives and understandings concerning their experiences of and readiness for the performative and organisational aspects of professional practice during the induction phase. In so doing, this review will identify any knowledge gaps in the current literature.

Theory: Performative and organisational aspects of teachers’ work

The theoretical framework for this study is the theory of professions. More specifically, as this actually represents a family of theories within the social sciences, we use theoretical frameworks related to the professional lives of educators derived from the work of Hargreaves (1994, 2000) and Datnow (2011). We argue that this theoretical framework is relevant for research concerning newly graduated teachers in general as well as for the field of PE teacher education (PETE) research in particular. However, the relationship between professional qualification and practical training with regard to teacher education and the qualifications required later in a teacher’s working life has been described as weak (Hammerness, 2013). For instance, studies argue that PETE has little impact on student teachers’ beliefs and practices when they actually start working in schools (Dowling, 2011; Moen, 2011). A dilemma facing teachers in all disciplines concerns the tension between their work as a professional practitioner in the classroom and their dependence on the organisational structure of their school and state governance (Andreassen, 2017; Molander & Terum, 2008; Wermke & Höstfält, 2014). Still, despite these known challenges, there is currently little research on qualifications and work-related experiences among PE teachers in particular (Løndal et al., 2021).

The literature concerning the teaching profession uses different terms to refer to different aspects of teachers’ qualifications. For example, Hargreaves (2000) uses the terms “professionalism” (i.e. improving quality and standards of practice) and “professionalisation” (i.e. improving status and standing). Moreover, building on the work of Hargreaves (1994, 2000), Datnow (2011) posits that performative work is directed towards a teacher’s individual accountability in terms of teaching and, further, that collaboration within a school as a specific type of organisation is both directed towards solving problems together and related to the school culture. In line with Datnow’s (2011) argument for operationalising and separating the two aspects of teachers’ professional work, we differentiate teachers’ professional work into the performative and organisational aspects of their practices. In addition, we base our operationalisation of the performative and organisational aspects on the work of Hermansen et al. (2018) in mapping of the characteristics of research on the teaching role in the Norwegian context. Here, the performative aspect refers to the individual teacher’s practice in the classroom, whereas the organisational aspect refers to collective issues, such as autonomy, status and social position, as well as forms of internal and external control over professional practice (Hermansen et al., 2018). A teacher’s professional knowledge and didactics when working with children in the classroom are central to the performative aspect (Hermansen et al., 2018). When the organisation of teachers’ work depends on institutional frameworks, both their collective position and their control and accountability regarding their own tasks are governed by the organisational aspect of professional teaching practice. Many tasks that teachers perform during the course of their professional work involve both a performative and an organisational aspect, with the two aspects being understood as having a mutually constitutive relationship. These operationalisations of the terms “performative” and “organisational” serve as analytical tools in this scoping review of newly graduated teachers’ professional experiences and readiness for professional practice.

Aim of the scoping review

To identify published research concerning how newly graduated PE teachers experience their readiness for professional practice, a scoping review was performed. This type of review provides a broad overview of a particular topic and offers a clear indication of the volume of literature available on it (Arksey & O’Malley, 2005; Daza et al., 2021; Forsström & Munthe, 2023; Grant & Booth, 2009; Keles et al., 2022; Munn et al., 2018). While scoping reviews can be conducted to achieve various objectives, such reviews cannot be regarded as final outputs (Cambell et al., 2023; Tricco et al., 2016). Still, a synthesis of research material such as a scoping review may contribute to a greater conceptual understanding of a given phenomenon (Newman & Gough, 2020), which in this review is the phenomenon of newly graduated PE teachers and their readiness for professional practice. While different disciplines have different epistemological foundations, the present scoping review is situated within the field of educational research. In this field, scoping reviews contribute to the ecology of knowledge summarisation that aims to determine what is currently known about a certain topic (Munthe et al., 2022, p. 133). The work of Arksey and O’Malley (2005) serves as a common reference for several review studies within different fields of research, including educational research. More specifically, a scoping review is a review that does not follow a fully systematic process, and it is used to describe the nature of a research field rather than to synthesise findings (e.g. Daza et al., 2021; Keles et al., 2022; Newman & Gough, 2020; Tricco et al., 2016). Inspired by Arksey and O’Malley (2005), the present review involved five main methodological stages: 1) formulating the research questions; 2) identifying relevant studies; 3) selecting the studies; 4) charting the data; and 5) collating, summarising, and reporting the results.

Research questions

In light of the consistently high policy demands facing the teaching profession, this scoping review seek to address the following research questions:

1) How is research conducted on the topic of newly graduated PE teachers?

2) What characteristics or factors relate to the experiences reported in such research?

3) What are the performative and organisational aspects described in such research?

Moreover, this scoping review summarises the results in order to provide a broad overview of the volume of available research, identify any knowledge gaps and determine any additional research required in the field.

Method

Identification of relevant studies

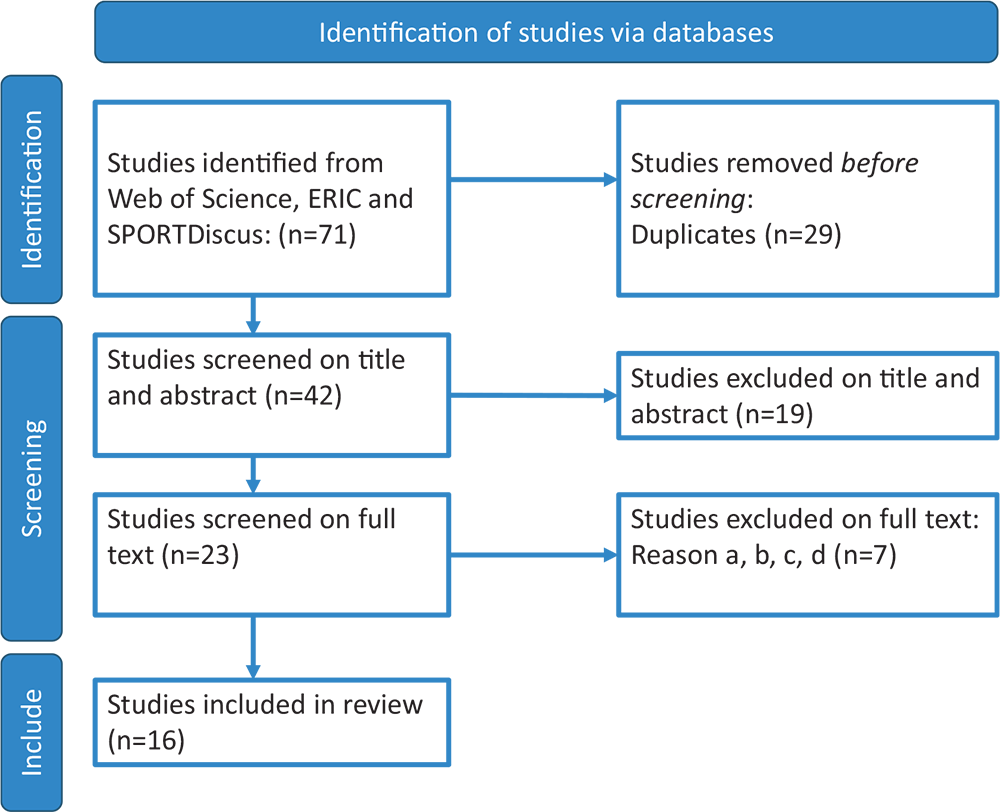

To identify relevant studies, the Web of Science, Education Resources Information Center (ERIC) and SPORTDiscus databases were searched using the following keywords: “physical education teachers” and “PE teachers” in combination with “novice”, “new(ly)” and “begin(ning/ner)” (“New* physical education teach*” or “novice physical education teach*” or “begin* physical education teach*” or “new PE teach*” or “novice PE teach*” or “begin* PE teach*”). To limit its scope, the search included only full-text peer-reviewed literature and excluded non-English literature. The initial search identified 71 studies. After any duplicates were removed, the number of studies was reduced to 42.

Study selection

The 42 studies identified during the database search were then screened based on information from the title and abstract of each, which further narrowed the number of studies down to 23. The predefined inclusion criteria were an examination of PE teachers, focusing on personal experiences during the first five years of teaching in a primary, secondary or high-school context. Next, the full text of each of the 23 articles was read. This stage of the screening process excluded seven articles that focused on (a) students attending a PE programme, (b) the investigation or implementation of mentoring programmes or learning communities, or (c) employment criteria for PE teachers, in addition to articles that (d) lacked methodological information. Based on the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) guidelines (Page et al., 2021),1 Figure 1 outlines the results of the search strategy and selection processes, which led to 16 articles being selected for the final review.

Figure 1. PRISMA flow diagram of the study selection and screening processes

Next, this scoping review performed a qualitative content analysis (Fauskanger & Mosvold, 2014; Patton, 2002) of the 16 selected studies, which entailed three steps for identifying important features of the data related to the research questions set out above. The digital software MAXQDA was used as an organisational support during the analysis for coding and categorisation of the data material and means that information is divided, systematized and elaborated to validate the development of themes from the data (Gibbs, 2014; Maxwell & Chmiel, 2014). The process was iterative rather than linear, meaning that we moved flexibly through the steps and repeated any steps necessary to ensure that the reviewed literature was converted in a comprehensive way (Arksey & O’Malley, 2005).

We began with an individual qualitative reading of each study to identify themes that provided an accurate reflection of the study’s content (Fauskanger & Mosvold, 2014). Moreover, to analyse the amount, nature and occurrence of content related to the study context (author(s), year of publication, methodological approach, sample size and years of teaching), we also performed a summative content analysis (Fauskanger & Mosvold, 2014). Next, we conducted a conventional content analysis of each study (i.e. research results), searching for textual content involving expressions linked to PE teachers’ experiences of and readiness for professional practice. The identified themes were developed by means of inductive open coding (Fauskanger & Mosvold, 2014; Patton, 2002) via an exploratory technique that involved marking, cutting and sorting the text (Ryan & Bernard, 2003) to arrange the data into main themes and subthemes, related to the professional framework (Hermansen et al., 2018). We first identified the following main themes related to the abstracts and keywords: subject content knowledge, classroom management, interaction and communication, school culture, role and position, professional development over several years and support. These themes were then further categorised into subthemes within the studies. Finally, we performed a directed content analysis (Fauskanger & Mosvold, 2014) to clarify how newly graduated PE teachers’ experiences of their professional readiness, as detailed in the 16 selected studies, in different aspects of their professional work. In this regard, the studies were deductively categorised based on concepts associated with the performative and organisational aspects, where the performative aspect refers to teachers’ practice in the classroom, while the organisational aspect refers to more collective issues, such as autonomy, status and social position, and to forms of internal and external control over professional practice (Hermansen et al., 2018).

Results

The methodological procedure described above resulted in the identification of 16 studies that met the inclusion criteria and were published between 1989 and 2018 (see Table 1).

Research on the topic of newly graduated PE teachers

The vast majority of the 16 identified studies concerning newly graduated PE teachers used qualitative methods (n = 15), while only one study obtained its findings quantitatively by analysing statistical data. The most commonly used qualitative method was the interview method, which was applied in 11 studies, including seven studies in which interviews were conducted in conjunction with other research methods. Observation was used in six studies, while written teacher reports (log [n = 1], diary [n = 1], report [n = 2] and journal [n = 2]) were used in six studies, including four that used written reports alongside other qualitative methods. Two studies analysed documents (e.g. lesson plans, calendars, curriculum plans, assessment notes, e-mail communications between participants and researchers) in combination with other qualitative methods.

The sample sizes of the identified studies varied. Nine studies involved one, two, three, five, or 12 participants, while six studies had larger sample sizes ranging from 21 to 62. One study was a literature review. The only quantitative study included in this review involved 104 participants, while the study that used written reports (teacher logs) as the research design involved 230 participants. Moreover, seven studies investigated newly graduated PE teachers during their first year of professional practice, five studies examined their first and second years of teaching, and two assessed their first five induction years. Two studies did not specifically mention the teaching years investigated but used the descriptive terms “induction years” and “beginning PE teachers.” An overview of the characteristics of the 16 studies included in this scoping review is provided in Table 1.

| Author(s), year | Country | Method | Sample size | Year(s) of teaching |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| O’Sullivan, 1989 | USA | Interviews, observations, written reports | 2 | First |

| Capel, 1993 | England | Survey | 104 | First and second |

| Macdonald, 1995 | Australia | Interviews | 22 | First and second |

| Napper-Owen and Phillips, 1995 | USA | Interviews, observations, field notes | 2 | First |

| Hebert and Worthy, 2001 | USA | Interviews | 1 | First |

| Blankenship and Coleman, 2009 | USA | Interviews, videotaped lessons, field notes, documents | 2 | First and second |

| Shoval et al., 2010 | Israel | Interviews | 62 | NR1 |

| Eldar et al., 2011 | Israel and USA | Written reports | 230 | First |

| Banville, 2015 | USA | Interviews, observations | 21 | First and second |

| Zach et al., 2015 | Israel | Written reports, focus groups | 45 | First |

| Gordon, 2016 | USA | Interviews, observations, field notes, teacher documents | 2 | First and second |

| MacPhail and Hartley, 2016 | Ireland | Interviews, written reports | 12 | First |

| Ensign and Woods, 2017 | USA | Literature review | NA2 | NA2 |

| Romar and Frisk, 2017 | Finland and Sweden | Interviews, observations | 3 | First |

| Costa Filho and Iaochite, 2018 | Brazil | Interviews | 5 | First five |

| González-Calvo and Fernández-Balboa, 2018 | Spain | Written reports | 1 | First five |

1Not recorded; 2Not applicable.

The review revealed that all 16 selected studies sought to identify, describe and analyse newly graduated PE teachers’ working lives, focusing on experiences from their perspective under different conditions (e.g. subject content knowledge, school culture, the teacher’s role and position, interaction and communication) and in the context of their professional work. These experiences will be discussed more comprehensively in the following sections.

Characteristics or factors related to experiences reported in the studies

A number of themes and subthemes reflecting newly graduated PE teachers’ reported experiences was generated from the textual content of the 16 selected studies. The subthemes were coded as positive (+) and/or negative (–) experiences based on how they were discussed in the studies. Table 2 presents the reported positive (+) and/or negative (–) experiences of newly graduated PE teachers, which are often written as (+/-) or (-/+) to clarify whether the weight of a particular experience was positive or negative. As many of the included studies addressed several topics, the total number of subthemes is higher than the number of studies related to a given theme.

| Experience | Subject content knowledge | 5 |

|---|---|---|

| +/– | Planning | 1 |

| +/– | Teaching | 5 |

| +/– | Student assessment | 3 |

| Classroom management | 7 | |

| – | Individualisation | 6 |

| –/+ | Autonomy | 2 |

| Interaction and communication | 15 | |

| +/– | Students | 10 |

| +/– | PE colleagues | 4 |

| –/+ | Other subject colleagues | 7 |

| – | Administration | 2 |

| + | Principal | 2 |

| –/+ | Parents | 5 |

| School culture | 10 | |

| – | Marginalisation | 9 |

| –/+ | Isolation | 6 |

| + | Autonomy | 1 |

| +/– | Familiarity with school culture | 3 |

| – | Overwhelmed by workload | 4 |

| Role and position | 8 | |

| +/– | Self-awareness | 7 |

| – | Role conflict | 3 |

| Professional development over several years | 4 | |

| –/+ | Second year | 2 |

| –/+ | Third year | 2 |

| Support | 11 | |

| –/+ | Formal support | 4 |

| +/– | Informal support | 6 |

| – | Lack of support | 5 |

The conventional content analysis identified the newly graduated PE teachers’ experiences of subject content knowledge as either positive or negative in accordance with their level of self-confidence regarding different subject content areas. Classroom management involved negative experiences concerning individualisation and revealed PE teachers to have trouble making independent decisions, although they were pleased to have autonomy in the form of independence. While interaction and communication with students were reported as positive, students who exhibited behavioural issues (e.g. passive behaviour, lack of motivation, verbal and physical violence) inhibited PE teachers’ ability to teach and so were coded as negative. Furthermore, relationships with PE colleagues and other subject colleagues were generally experienced as positive, although they could be negative if a lack of collaboration, differences in curriculum perspectives and/or a lack of respect were experienced. Interaction and communication with parents were experienced as challenging. While principals were found to be supportive, school administration staff were reported to provide little support.

Feelings of isolation and marginalisation were identified as negative and related to when the school culture (i.e. students, parents, colleagues, administration and principal) placed less emphasis on student learning in relation to PE. Newly graduated PE teachers felt overwhelmed by their workload due to being responsible for many tasks other than teaching. Positive experiences were reported by teachers who were familiar with the school culture and/or experienced autonomy among the teaching staff. The role and position were associated with negative experiences for PE teachers due to the need to fulfil and balance various roles. They reported positive experiences related to self-awareness of their position, which helped them to become an appreciated member of the school culture. At the end of the third year, professional development was recognised in PE teachers’ beliefs and actions, with them beginning to think and act in a more balanced way. The research data identified both positive and negative experiences regarding formal (i.e. mentoring and in-service courses online or in person) and informal support (i.e. supportive or nurturing school environment). Here, informal support was experienced more favourably than formal support, while some teachers experienced not receiving the support they required.

Performative and organisational aspects reported

By means of the directed content analysis, seven themes of experiences reported in the 16 selected studies were categorised into different aspects of professional teaching practice: performative and/or organisational aspects. Some studies combined the two aspects; therefore, the number of results was higher than the total number of studies (see Table 3).

| Experiences of the performative aspect (n = 13) | |

| Subject content knowledge | 5 |

| Classroom management | 7 |

| Interaction and communication (students) | 10 |

| Experiences of the organisational aspect (n = 15) | |

| Interaction and communication (PE colleagues, other subject colleagues, principal, administration and parents) | 13 |

| School culture | 10 |

| Experiences of performative and organisational aspects (n = 14) | |

| Role and position | 8 |

| Professional development over several years | 4 |

| Support | 11 |

The performative aspect of professional teaching work covered experiences related to subject content knowledge, classroom management, and interaction and communication with students. Moreover, experiences related to interaction and communication with PE colleagues, other subject colleagues, the principal, the administration and parents, as well as those related to the school culture, comprised the organisational aspect. The themes of role and position, professional development over several years and support were applicable to the combination of the performative and organisational aspects.

Discussion

This scoping review mapped the published research concerning newly graduated PE teachers’ experiences, as categorised into the performative and/or organisational aspects of their professional practice. In this part we elaborate on how the results align with the theory of professions framework (Hermansen et al., 2018) and previous research presented in the introduction. The discussion is organised in accordance with the research questions and the conclusion summarises the results in order to provide a broad overview of the available research, identify potential knowledge gaps and additional research required in the field.

From self-focused to student-oriented

When entering the teaching profession, newly graduated PE teachers tend to be preoccupied with the performative aspect of teaching PE (Banville, 2015; Gordon, 2016; Macdonald, 1995). They later become accustomed to managing other duties outside the classroom but within the school context (i.e. organisational work) (Banville, 2015). The workload associated with all of these tasks appears to overwhelm PE teachers (Shoval et al., 2010), causing tension between their work as a professional practitioner in the classroom and their dependence on the organisational structure of their school and state governance, which has previously been identified as a dilemma facing all those in the teaching profession (Andreassen, 2017; Molander & Terum, 2008; Wermke & Höstfält, 2014). Moreover, newly graduated PE teachers are recognised by the studies included in this scoping review to be concerned with their own development during their first induction year, which results in them concentrating on what and how to teach (i.e. subject content knowledge and classroom management). The studies that include teachers in their second year report a shift in this regard, with the teachers’ focus becoming more student-oriented, which indicates the progression of learning and the proper implementation of subject content knowledge (Banville, 2015; Gordon, 2016). Thus, it appears that newly graduated PE teachers must become familiar with the school context if they are to be able to practice their work professionally (Eldar et al., 2011).

The way newly graduated PE teachers manage the performative work of planning, teaching and assessing (e.g. selecting the criteria for assigning a grade, providing specific feedback) relates to their level of self-confidence regarding different subject content areas (Romar & Frisk, 2017). When considering PE teachers’ experiences of leading students’ learning processes (individualisation), the assessed studies report that new graduates exhibit inadequate knowledge of the differentiated activities, instruction techniques and learning strategies appropriate for addressing individual student differences, for students in general (Napper-Owen & Phillips, 1995) and for students with special needs in particular (Eldar et al., 2011; Ensign & Woods, 2017). The feeling of having insufficient knowledge is understandable given that newly graduated PE teachers are more self-focused than outward looking when they start their professional practice (Banville, 2015; Gordon, 2016). The examined studies reveal ambivalence among the PE teachers’ experiences of autonomy: they experience difficulties in having to make independent decisions straight away, although they are satisfied with having autonomy in the form of independence (Macdonald, 1995; Zach et al., 2015).

Interaction and communication are included within the scope of 15 out of 16 assessed studies, and they are categorised here as both a performative aspect (with students) and an organisational aspect (with PE colleagues, other subject colleagues, the principal, the administration and parents). While interaction and communication with students are reported as positive experienced in several studies (Hebert & Worthy, 2001), students who exhibit behavioural issues (e.g. passive behaviour, lack of motivation, verbal and physical violence) hinder PE teachers’ ability to teach (Eldar et al., 2011). Relationships with PE colleagues (Napper-Owen & Phillips, 1995) and other subject colleagues (Capel, 1993) are generally reported as positive, although they are experienced as challenging when there is a lack of collaboration with PE colleagues who do not view them as equals due to their inexperience (MacPhail & Hartley, 2016) and when there is a lack of collegiality, differences in curriculum perspectives and/or a lack of respect from other subject teachers (O’Sullivan, 1989). Here, we again find ambivalence in that the relationships are experienced as both positive and challenging at the same time. This ambivalence reflects a trend in the research data: work related to both interaction and communication seems to become more challenging when newly graduated PE teachers elaborate on their experiences of the various relationships.

Collaborative relationships in school

In terms of relationships with colleagues at the school as an organisational aspect, the studies use unambiguous statements and language to relate newly graduated PE teachers’ feelings of both isolation (Ensign & Woods, 2017) and marginalisation (Macdonald, 1995). These studies report that the school culture (i.e. students, parents, colleagues, administration and principal) places less emphasis on PE and has lower expectations of students’ learning in relation PE due to considering it a non-academic subject. As the PE teaching environment tends to be located away from other classrooms, PE teachers are vulnerable to becoming withdrawn and feeling separate from the usual collegial culture within the school environment (Ensign & Woods, 2017), especially if the school has only one PE teacher (MacPhail & Hartley, 2016) or if there are tensions within the PE department as a whole (Banville, 2015). By contrast, some newly graduated PE teachers may not experience isolation due to the teaching staff having autonomy to value ideas and make decisions as well as due to there being openness to the introduction of system-wide initiatives and less familiar sports (Zach et al., 2015).

Linked to the theme of support, four studies consider PE teachers’ interaction and communication with the school administration and the principal. The administration staff are reported to provide little support, with the related communication (about students) being described as inaccurate or even non-existent (Eldar et al., 2011; Macdonald, 1995). Conversely, interaction and communication with the principal are experienced as indicative of a supportive relationship that assigns newly graduated PE teachers’ responsibility, treats them as equal members of staff and displays a caring attitude, particularly through providing support when dealing with parents (Blankenship & Coleman, 2009; O’Sullivan, 1989).

Teachers’ organisational work when interacting and communicating with parents is experienced as challenging (Romar & Frisk, 2017). Indeed, when parents do not understand and/or value PE as a subject, PE teachers experience difficulties persuading parents to encourage and facilitate student learning (O’Sullivan, 1989). Some newly graduated PE teachers actually come to dislike direct conversations with parents (González-Calvo & Fernández-Balboa, 2018) due to experiences with parents who behave in an obnoxious manner (O’Sullivan, 1989) or threaten them (González-Calvo & Fernández-Balboa, 2018). In the reviewed studies, conflict with parents is reported to stem from the lack of a tradition of collaboration with families within the school. Another reason for conflict is reported to be the fact that newly graduated PE teachers often only have part-time or temporary jobs, which makes it difficult for them to build relationships (González-Calvo & Fernández-Balboa, 2018). Given the difficulty of identifying a collaborative relationship between teachers, students and parents in the reviewed studies, we suggest this to be a valuable topic for future research.

Balance the roles

The studies identify role conflict challenges when newly graduated PE teachers are expected to balance the roles of mentor, friend, leader, authority figure, coach, and counsellor. Initially, one role must suffer for another to succeed (Ensign & Woods, 2017; Macdonald, 1995; MacPhail & Hartley, 2016). This is a part of PE teachers’ professional work where the performative and organisational aspects cannot be separated due to the role conflict that can occur both inside and outside the classroom (Hermansen et al., 2018). Another experience reported in the studies that combines the performative and organisational aspects concerns PE teachers’ experiences of their position as new graduates. They have self-awareness of entering the teaching profession with new strengths, individual ambitions (Shoval et al., 2010), innovative knowledge (Eldar et al., 2011) and an active role (Blankenship & Coleman, 2009), which helps them to become an appreciated member of the school culture (Zach et al., 2015). Both the nature of PE as a subject (i.e. active social involvement) and newly graduated teachers’ relative youth are reported as advantages when it comes to their relationships with students (Hebert & Worthy, 2001). Most novice teachers are aware that they still have much to learn (Banville, 2015); therefore, they invest much time and energy in their job (Shoval et al., 2010). Hebert and Worthy (2001) note that such investment is easier for teachers who do not have family responsibilities.

Yet, while newly graduated PE teachers are generally aware of still having much to learn, the work of Macdonald (1995) and González-Calvo and Fernández-Balboa (2018) highlights how some teachers do not have sufficient skills to critically assess their own performance during the first three years of their professional practice. However, by the end of the third year, a radical shift is observed in PE teachers’ beliefs and actions, as they begin to think and act in a more balanced way because they recognise the importance of collaborating with parents for the good of students (González-Calvo & Fernández-Balboa, 2018).

The examples of support in the selected studies show that newly graduated PE teachers experience their induction to the profession as challenging. Few PE teachers receive sufficient support (MacPhail & Hartley, 2016; Shoval et al., 2010), while those who do receive such support feel strongly that it should be maintained throughout their second year (Banville, 2015; Napper-Owen & Phillips, 1995). In this regard, Napper-Owen and Phillips (1995) stress that support is more crucial for PE teachers in smaller school districts due to there being fewer peers in their subject area. Still, the reviewed studies indicate that support intended to help newly graduated PE teachers with their professional practice is being demanded by PE teachers themselves (Shoval et al., 2010). This desire and need for support on the part of PE teachers as they enter the teaching profession emphasises how professional qualification is an ongoing learning process that develops through education and throughout a professional career (Darling-Hammond, 2017; Ingersoll & Collins, 2018). Both the formal (i.e. mentoring within the school environment or in-service training courses) (e.g. Costa Filho & Iaochite, 2018) and informal support (i.e. school with supportive and nurturing colleagues and/or principal) (Blankenship & Coleman, 2009) reported in the studies are experienced by PE teachers as useful (MacPhail & Hartley, 2016), although whether or not such support is considered adequate by new graduates depends on who provides it (Napper-Owen & Phillips, 1995). Given that informal support is more favourably experienced than formal support (Ensign & Woods, 2017), an important goal for future studies is to determine what constitutes appropriate support for newly graduated PE teachers.

Concluding remarks

The research data presented in this scoping review reflect a problem-oriented trend (in both the performative and organisational aspects) whereby positive experiences become negative when newly graduated PE teachers are asked to elaborate on those experiences. Although newly graduated PE teachers are qualified in the field of PE, their professional practice depends on other people’s participation and cooperation as well as on their own experienced autonomy. Thus, there are many aspects of professional practice that PE teachers experience as difficult during their first five years in the profession.

While still limited, research on newly graduated PE teachers’ experiences is developing, with prior studies emphasising the need for further investigation in the field. As the teaching profession’s qualifications include various aspects of professional teaching work, there exists a need for extended research in this regard. It may be the case that research on newly graduated PE teachers has traditionally adopted a problem-oriented approach; however, scoping reviews cannot generally be regarded as a final output in their own right (Grant & Booth, 2009; Tricco et al., 2016). Through this scoping review, we have identified the main themes and subthemes concerning positive and negative experiences related to many different tasks that PE teachers must cope with and that newly graduated PE teachers must perform for the first time during their induction period. In this review, we have also identified a number of knowledge gaps within the research on newly graduated PE teachers, such as communication and collaboration with parents and colleagues, in addition to what constitutes appropriate support for newly graduated PE teachers. We suggest these to be valuable topics for future research. In general, there is a need for more research on the many small and larger tasks of PE teachers when viewed in light of the performative and organisational aspects of teaching practice. Such efforts may highlight what newly graduated PE teachers are successful at and what professional knowledge they bring with them from their teacher training. Moreover, it must be noted that a continued research focus on negative experiences may hinder the development of new questions concerning the valuable resource that newly graduated PE teachers represent.

References

- Amdal, I. I., & Ulvik, M. (2019). Nye læreres erfaringer med skolen som organisasjon [New teachers’ experiences with the school as an organisation]. Nordisk Tidsskrift for Utdanning og Praksis, 13(1), 5–24. https://doi.org/10.23865/up.v13.1834

- Andreassen, T. A. (2017). Profesjonsutøvelse i en organisatorisk kontekst [Professional practice in an organisational context]. In S. Mausethagen & J.-C. Smeby (Eds.), Kvalifisering til profesjonell yrkesutøvelse [Qualification for professional practice] (pp. 140–152). Universitetsforlaget.

- Arksey, H., & O’Malley, L. (2005). Scoping studies: Towards a methodological framework. International Journal of Social Research Methodology, 8(1), 19–32. https://doi.org/10.1080/1364557032000119616

- Banks, S. (2003). From oaths to rulebooks: A critical examination of codes of ethics for the social professions. European Journal of Social Work, 6(2), 133–144. https://doi.org/10.1080/1369145032000144403

- Banville, D. (2015). Novice physical education teachers learning to teach. Journal of Teaching in Physical Education, 34(2), 259–277. https://doi.org/10.1123/jtpe.2013-0129

- Blankenship, B. T., & Coleman, M. M. (2009). An examination of “wash-out” and workplace conditions of beginning physical education teachers. Physical Educator, 66(2), 97–111.

- Braun, V., & Clarke, V. (2006). Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qualitative Research in Psychology, 3(2), 77–101. https://doi.org/10.1191/1478088706qp063oa

- Campbell, F., Tricco, A. C., Munn, Z., Pollock, D., Saran, A., Sutton, A., White, H., & Khalil, H. (2023). Mapping reviews, scoping reviews, and evidence and gap maps (EGMs): The same but different—The “Big Picture” review family. Systematic Reviews, 12(45). https://doi.org/10.1186/s13643-023-02178-5

- Capel, S. A. (1993). Anxieties of beginning physical education teachers. Educational Research, 35(3), 281–289. https://doi.org/10.1080/0013188930350308

- Caspersen, J., & Raaen, F. D. (2014). Novice teachers and how they cope. Teachers and Teaching, 20(2), 189–211. https://doi.org/10.1080/13540602.2013.848570

- Christophersen, K. A., Elstad, E., Solhaug, T., & Turmo, A. (2016). Antecedents of student teachers’ affective commitment to the teaching profession and turnover intention. European Journal of Teacher Education, 39(3), 270–286. https://doi.org/10.1080/02619768.2016.1170803

- Cochran-Smith, M. (2005). Studying teacher education: What we know and need to know. Journal of Teacher Education, 56(4), 301–306.

- Costa Filho, R. A., & Iaochite, R. T. (2018). Constitution of self-efficacy in the early career of physical education teachers. Journal of Physical Education and Sport, 18(4), 2410–2416. https://doi.org/10.7752/jpes.2018.04363

- Darling-Hammond, L. (2006). Constructing 21st-century teacher education. Journal of Teacher Education, 57(3), 300–314. https://doi.org/10.1177/0022487105285962

- Darling-Hammond, L. (2017). Teacher education around the world: What can we learn from international practice? European Journal of Teacher Education, 40(3), 291–309. https://doi.org/10.1080/02619768.2017.1315399

- Datnow, A. (2011). Collaboration and contrived collegiality: Revisiting Hargreaves in the age of accountability. Journal of Educational Change, 12(2), 147–158. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10833-011-9154-1

- Day, C., & Sachs, J. (2004). Professionalism, performativity and empowerment: Discourses in the politics, policies and purposes of continuing professional development. In C. Day & J. Sachs (Eds.), International handbook on the continuing professional development of teachers (pp. 3–32). Open University Press.

- Dowling, F. (2011). “Are PE teacher identities fit for postmodern schools or are they clinging to modernist notions of professionalism?” A case study of Norwegian PE teacher students’ emerging professional identities. Sport, Education and Society, 16(2), 201–222. https://doi.org/10.1080/13573322.2011.540425

- Eldar, E., Ayvazo, S., Talmor, R., & Harari, I. (2011). Difficulties and successes during induction of physical education teachers. International Journal of Physical Education, 48(1), 33–42.

- Ensign, J., & Woods, A. M. (2017). Navigating the realities of the induction years: Exploring approaches for supporting beginning physical education teachers. Quest, 69(1), 80–94. https://doi.org/10.1080/00336297.2016.1152983

- Fauskanger, J., & Mosvold, R. (2014). Innholdsanalysens muligheter i utdanningsforskning [The possibilities of content analysis in educational research]. Norsk Pedagogisk Tidsskrift, 98(2), 127–139.

- Feiman-Nemser, S. (2001a). From preparation to practice: Designing a continuum to strengthen and sustain teaching. Teachers College Record, 103(6), 1013–1055.

- Feiman-Nemser, S. (2001b). Helping novices learn to teach: Lessons from an exemplary support teacher. Journal of Teacher Education, 52(1), 17–30. https://doi.org/10.1177/0022487101052001003

- Fernández-Balboa, J. M. (1997). Knowledge base in physical education teacher education: A proposal for a new era. Quest, 49(2), 161–181. https://doi.org/10.1080/00336297.1997.10484231

- Forsström, S. E., & Munthe, E. (2023). What characterizes Nordic research on initial teacher education: A systematic scoping review. Nordic Studies in Education, 43(3), 241–259. https://doi.org/10.23865/nse.v43.5588

- Frankel, M. S. (1989). Professional codes: Why, how, and with what impact? Journal of Business Ethics, 8(2–3), 109–115. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF00382575

- Gibbs, G. R. (2014). Using software in qualitative analysis. In U. Flick, K. Metzler, & W. Scott (Eds.), The Sage handbook of qualitative data analysis (pp. 277–294). Sage.

- González-Calvo, G., & Fernández-Balboa, J. M. (2018). A qualitative analysis of the factors determining the quality of relations between a novice physical education teacher and his students’ families: Implications for the development of professional identity. Sport, Education and Society, 23(5), 491–504. https://doi.org/10.1080/13573322.2016.1208164

- Gordon, E. J. (2016). Concerns of the novice physical education teacher. The Physical Educator, 73(4), 652–670. https://doi.org/10.18666/TPE-2016-V73-I4-7069

- Grant, M. J., & Booth, A. (2009). A typology of reviews: An analysis of 14 review types and associated methodologies. Health Information & Libraries Journal, 26(2), 91–108. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1471-1842.2009.00848.x

- Hammerness, K. (2013). Examining features of teacher education in Norway. Scandinavian Journal of Educational Research, 57(4), 400–419. https://doi.org/10.1080/00313831.2012.656285

- Hargreaves, A. (1994). Changing teachers, changing times: Teachers’ work and culture in the postmodern age. Cassell.

- Hargreaves, A. (2000). Four ages of professionalism and professional learning. Teachers and Teaching, 6(2), 151–182. https://doi.org/10.1080/713698714

- Hebert, E., & Worthy, T. (2001). Does the first year of teaching have to be a bad one? A case study of success. Teaching and Teacher Education, 17(8), 897–911. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0742-051X(01)00039-7

- Hermansen, H., Lorentzen, M., Mausethagen, S., & Zlatanovic, T. (2018). Hva kjennetegner forskning på lærerrollen under Kunnskapsløftet? En forskningskartlegging av studier av norske lærere, lærerstudenter og lærerutdannere [What characterises research on teacher roles during knowledge promotion? A systematic review of studies of Norwegian teachers, student teachers and teacher educators]. Acta Didactica Norge, 12(1), 1–36. http://dx.doi.org/10.5617/adno.4351

- Ibrahim, A. S. (2012). The learning needs of beginning teachers in the United Arab Emirates. Journal of Education for Teaching, 38(5), 539–549. https://doi.org/10.1080/02607476.2013.739791

- Ingersoll, R. M. (2003, September). Is there really a teacher shortage? A research report. Center for the Study of Teaching and Policy. https://www.gse.upenn.edu/pdf/rmi/Shortage-RMI-09-2003.pdf

- Ingersoll, R. M., & Collins, G. J. (2018). The status of teaching as a profession. In J. H. Ballantine, J. Z. Spade, & J. M. Stuber (Eds.), Schools and society: A sociological approach to education (6th ed., pp. 199–213). Sage Publications.

- Keles, S., ten Braak, D., & Munthe, E. (2022). Inclusion of students with special education needs in Nordic countries: A systematic scoping review. Scandinavian Journal of Educational Research. https://doi.org/10.1080/00313831.2022.2148277

- Kunnskapsdepartementet. (2020, June 5). Forskrift om rammeplan for lærerutdanning i praktiske og estetiske fag for trinn 1–13 [Regulations on a framework plan for teacher education in practical and aesthetic subjects for stages 1–13] (LOV-2005-04-01-15-§3-2). Lovdata. https://lovdata.no/dokument/LTI/forskrift/2020-06-04-1134

- Lawson, H. A. (1983). Toward a model of teacher socialization in physical education: Entry into schools, teachers’ role orientations, and longevity in teaching (part 2). Journal of Teaching in Physical Education, 3(1), 3–15.

- Løndal, K., Borgen, J. S., Hallås, B. O., Moen, K. M., & Gjølme, E. G. (2021). Forskning for fremtiden? En oversiktsstudie av empirisk forskning på det norske skolefaget kroppsøving i perioden 2010–2019 [Research for the future? An overview study of empirical research on the Norwegian school subject physical education in the period 2010–2019]. Journal for Research in Arts and Sports Education, 5(3). https://doi.org/10.23865/jased.v5.3100

- Macdonald, D. (1995). The role of proletarianization in physical education teacher attrition. Research Quarterly for Exercise and Sport, 66(2), 129–141. https://doi.org/10.1080/02701367.1995.10762220

- MacPhail, A., & Hartley, T. (2016). Linking teacher socialization research with a PETE program: Insights from beginning and experienced teachers. Journal of Teaching in Physical Education, 35(2), 169–180. https://doi.org/10.1123/jtpe.2014-0179

- Mäkelä, K., Hirvensalo, M., & Whipp, P. R. (2014). Should I stay or should I go? Physical education teachers’ career intentions. Research Quarterly for Exercise and Sport, 85(2), 234–244. https://doi.org/10.1080/02701367.2014.893052

- Maxwell, J. A., & Chmiel, M. (2014). Notes toward a theory of qualitative data analysis. In U. Flick, K. Metzler, & W. Scott (Eds.), The Sage handbook of qualitative data analysis (pp. 21–34). Sage.

- McDiarmid, G. W., & Clevenger-Bright, M. (2008). Rethinking teacher capacity. In M. Cochran-Smith, S. Feiman-Nemser, D. J. McIntyre, & K. E. Demers (Eds.), Handbook of research on teacher education: Enduring questions and changing contexts (3rd ed., pp. 134–156). Routledge.

- Moen, K. M. (2011). “Shaking or stirring?” A case study of physical education teacher education in Norway [Unpublished doctoral dissertation]. Norwegian School of Sport Sciences.

- Molander, A., & Terum, L. I. (2008). Profesjonsstudier – en introduksjon [Professional studies – An introduction]. In A. Molander & L. I. Terum (Eds.), Profesjonsstudier (pp. 13–27). Universitetsforlaget.

- Munn, Z., Peters, M. D., Stern, C., Tufanaru, C., McArthur, A., & Aromataris, E. (2018). Systematic review or scoping review? Guidance for authors when choosing between a systematic or scoping review approach. BMC Medical Research Methodology, 18(1), 143. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12874-018-0611-x

- Napper-Owen, G. E., & Phillips, D. A. (1995). A qualitative analysis of the impact of induction assistance on first-year physical educators. Journal of Teaching in Physical Education, 14(3), 305–327. https://doi.org/10.1123/jtpe.14.3.305

- Newman, M., & Gough, D. (2020). Systematic reviews in educational research: Methodology, perspectives and application. In O. Zawacki-Richter, M. Kerres, S. Bedenlier, M. Bond, & K. Buntins (Eds.), Systematic reviews in educational research methodology, perspectives and application (pp. 3–22). Springer VSOpen Access.

- Ní Chróinín, D., Fletcher, T., & O’Sullivan, M. (2018). Pedagogical principles of learning to teach meaningful physical education. Physical Education and Sport Pedagogy, 23(2), 117–133. https://doi.org/10.1080/17408989.2017.1342789

- NOU 2022: 13 (2022). Med videre betydning. Et helhetlig system for kompetanse- og karriereutvikling i barnehage og skole [With further meaning. A comprehensive system for competence and career development in kindergarten and school]. Kunnskapsdepartementet. https://www.regjeringen.no/no/dokumenter/nou-2022-13/id2929000/

- Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development. (2018, April 5). The future of education and skills. Education 2030. OECD. http://www.oecd.org/education/2030-project/contact/E2030_Position_Paper_(05.04.2018).pdf

- Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development. (2019a). OECD future of education 2030. Making physical education dynamic and inclusive for 2030. International curriculum analysis. OECD. https://www.oecd.org/education/2030-project/contact/OECD_FUTURE_OF_EDUCATION_2030_MAKING_PHYSICAL_DYNAMIC_AND_INCLUSIVE_FOR_2030.pdf

- Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development. (2019b, May 21). TALIS 2018 results: Teachers and school leaders as lifelong learners. OECD. https://read.oecd-ilibrary.org/education/talis-2018-results-volume-i_1d0bc92a-en#page1

- O’Sullivan, M. (1989). Failing gym is like failing lunch or recess: Two beginning teachers’ struggle for legitimacy. Journal of Teaching in Physical Education, 8(3), 227–242.

- Page, M. J., McKenzie, J. E., Bossuyt, P. M., Boutron, I., Hoffmann, T. C., Mulrow, C. D., Shamseer, L., Tetzlaff, J. M., Akl, E. A., Brennan, S. E., Chou, R., Glanville, J., Grimshaw, J. M., Hrobjartsson, A., Lalu, M. M., Li, T., Loder, E. W., Mayo-Wilson, E., McDonald, S., McGuinness, L. A., Stewart, L. A., Thomas, J., … Moher, D. (2021). The PRISMA 2020 statement: An updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ, 372(71). https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.n71

- Patton, M. Q. (2002). Qualitative analysis and interpretation. In M. Q. Patton (Ed.), Qualitative research & evaluation methods (3rd ed., pp. 431–515). Sage.

- Rasmussen, J., & Holm, C. (2012). In pursuit of good teacher education: How can research inform policy? Reflecting Education, 8(2), 62–71.

- Romar, J. E., & Frisk, A. (2017). The influence of occupational socialization on novice teachers’ practical knowledge, confidence and teaching in physical education. Qualitative Research in Education, 6(1), 86–116.

- Ryan, G. W., & Bernard, H. R. (2003). Techniques to identify themes. Field Methods, 15(1), 85–109. https://doi.org/10.1177%2F1525822X02239569

- Sachs, J. (2016). Teacher professionalism: Why are we still talking about it? Teachers and Teaching, 22(4), 413–425. https://doi.org/10.1080/13540602.2015.1082732

- Schempp, P. G., & Graber, K. (1992). Teacher socialization from a dialectical perspective: Pretraining through induction. Journal of Teaching in Physical Education, 11, 329–348.

- Shoval, E., Erlich, I., & Fejgin, N. (2010). Mapping and interpreting novice physical education teachers’ self-perceptions of strengths and difficulties. Physical Education and Sport Pedagogy, 15(1), 85–101. https://doi.org/10.1080/17408980902731350

- Smeby, J.-C., & Mausethagen, S. (2017). Profesjonskvalifisering [Professional qualification]. In J.-C. Smeby & S. Mausethagen (Eds.), Kvalifisering til profesjonell yrkesutøvelse (pp. 11–20). Universitetsforlaget.

- Tait, M. (2008). Resilience as a contributor to novice teacher success, commitment, and retention. Teacher Education Quarterly, 35(4), 57–75.

- Templin, T. J., Padaruth, S., Sparkes, A. C., & Schempp, P. G. (2017). In K. L. Gaudreault & K. A. R. Richards (Eds.), Teacher socialization in physical education: New perspectives (pp. 11–29). Routledge

- Thue, F. W. (2017). Lærerrollen lag på lag – et historisk perspektiv [The teacher role layer by layer – A historical perspective]. Norsk Pedagogisk Tidsskrift, 101(01), 92–116.

- Tricco, A. C., Lillie, E., Zarin, W., O’Brien, K., Colquhoun, H., Kastner, M., Levac, D., Ng, C., Sharpe, J. P., & Wilson, K. (2016). A scoping review on the conduct and reporting of scoping reviews. BMC Medical Research Methodology, 16(1), 1–10. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12874-016-0116-4.

- Tricco, A. C., Lillie, E., Zarin, W., O’Brien, K. K., Colquhoun, H., Levac, D., Moher, D., Peters, M. D. J., Horsley, T., Weeks, L., Hempel, S., Akl, E. A., Chang, C., McGowan, J., Stewart, L., Hartling, L., Aldcroft, A., Wilson, M. G., Garritty, C., Lewin, S., … Straus, S. E. (2018). PRISMA Extension for Scoping Reviews (PRISMA-ScR): Checklist and Explanation. Annals of internal medicine, 169(7), 467–473. https://doi.org/10.7326/M18-0850

- Wermke, W., & Höstfält, G. (2014). Contextualizing teacher autonomy in time and space: A model for comparing various forms of governing the teaching profession. Journal of Curriculum Studies, 46(1), 58–80. https://doi.org/10.1080/00220272.2013.812681

- Zach, S., Stein, H., Sivan, T., Harari, I., & Nabel-Heller, N. (2015). Success as a springboard for novice physical education teachers in their efforts to develop a professional career. Journal of Teaching in Physical Education, 34(2), 278–296. https://doi.org/10.1123/jtpe.2014-0007