Introduction

Creativity is defined in this paper as the ability to “come up with new ideas and solutions” and the “willingness to question ideas” (Avvisati et al., 2013, p. 229), and creative thinking is defined in this paper as “purposeful, self-regulatory judgment which results in interpretation, analysis, evaluation, and inference” (Facione et al., 2011, p. 27). Both are considered key skills for 2030’s learners (OECD, 2019) and recognised by the forthcoming Programme for International Student Assessment (PISA, 2022) tests of young people’s creative thinking. These definitions encompass “components of metacognition, social and emotional skills (reflection and evaluation within a cultural context), attitudes and values (moral judgement and integration with one’s own goals and values), reflection and action” (OECD, 2019, p. 7). Therefore, creativity and critical thinking have vital international importance in education for European governments because they are central to finding solutions to complex problems.

However, whilst creativity is valued currently within global policy critiques raise concerns about a focus on entrepreneurial goals at the expense of creativity as a concept for democratic, ethical and relational goals (Sheridan-Rabideau, 2010). Creativity and wellbeing have recently been highlighted as key areas of 21st century learning (Celume et al., 2017; Cremin & Chappell, 2019; Stephenson, 2023). However, Wyse and Ferrari’s (2015) research investigating the place of creativity in the national curricula of the 27 member states of the EU (EU 27) and in the UK, found that creativity was a recurring element of curricula, but its incidence varied widely, suggesting that opportunities for creative learning are inequitable for learners across many European states.

As artist educators, we are involved in a three-year Erasmus+ funded project, “arted,” which aims to transfer the knowledge of artists working in education to school and home contexts in order to support equitable creative arts learning opportunities for young people. The project involves a wide range of artist educators practicing in six partner countries to co-produce interactive guides which will support teachers, pre-service teachers and parents or carers, to engage in creative arts learning with young people. Our project was particularly interested in the links between children’s proactive wellbeing and creative arts learning because learning through the expressive arts activates emotions, relationships and sensibilities (Holochwost et al., 2020). This paper critically explores our experiences as four artist-educator-researchers working across differing European countries, namely, England, Iceland, Germany, and Greece, in order to collectively frame our pedagogical guides for teachers within the project.

The relationship between policy, curriculum and pedagogy

Studies by the European Commission (2009) into teachers’ perceptions of creativity across 32 European countries found that an overwhelming majority of teachers believe that creativity can be applied to every domain of knowledge and to subject. However, barriers to successful teacher innovation and creative classroom learning practices across European schools fall into varying categories arising from political, policy, curriculum, and economic structures. These include functionalist summative testing, teacher or school target regimes, orthodox transmission methods of learning, analogue uses of digital technologies alongside philosophical or ideological mindsets (Banaji et al., 2013). Arguably, this can affect teacher confidence in the creative arts and therefore pupil learning opportunities. Additionally, national policy approaches differ in positioning creative arts subjects within their curricula.

There are different ontological positions from which policy in schools and teachers can be viewed (Ball et al., 2011). On the one hand, policies make up and make possible teacher subjects – as producers and consumers of policy, as readers and writers of policy (policy as text or steering documents). On the other hand, policies in schools are subject to complex processes of interpretation and translation. Within this paper we are interested in mapping the ways in which policy is lived, enacted and mediated by artist-educators as agents, and the possibility for action within policy (policy as discourse). We agree that both views are necessary to understand and problematise the work of policy and “policy work” in schools but that neither view is sufficient on its own (Ball et al., 2011). In the case of the creative arts, policy contradictions are highlighted from country to country on a macro level depending on the perceived status placed on creative learning within curriculum policy and on a meso and micro level, on how that policy is translated into classrooms.

Rhizomatics and the artist educator

For philosopher Guatarri (2013), creativity is a political desire to create new openings, flows and potentials within capitalist societies, referred to as schizophrenic thought. This definition of creativity is an interesting way to view the “policy work” of artist-educators (artists working in education). We apply Deleuzoguattarian theory (Deleuze & Guattari, 2004), to examine our collective pedagogical positions, in relation to differing European policy contexts through rhizo-textual analysis (Honan, 2004, 2007) and schizo-thinking (Guattari, 2013). The reading of policy is often linear and monological, favouring policy makers through structuralist understanding (Honan, 2007). Deleuzoguattarian theory, however, also posits the text as rhizomatic, or multi-directional offering potential movement away from a limiting position. A Deleuzoguattarian reading of the policy text would therefore focus on how policy works or functions, and what it produces.

Whilst many studies explore creative learning from the teachers’ perceptions, research lacks insights into the role of the artist in education, also evidenced through linear funding reports (Cremin & Chappell, 2019). In line with Honan’s use of textual-rhizomatic analysis (2015), we argue that reading our own pedagogical movements as “policy actors” (Ball et al., 2011) could offer new connections between differing education policy and practices across European contexts for educators. Our practices are seen as “lines of flight” or shifts away from the dominant force (Deleuze, 1995, p. 85), illuminating pedagogical movement within dominant policy texts. These readings aim to disrupt common assumptions about policy, which views the policy position of teachers as receivers (Ball et al., 2011). This exploration was utilised as a way to collectively frame our pedagogical guides for teachers, parents and pre-service teachers across the project, which aimed to create more equitable arts opportunities for young people within education.

Our rhizomatic thinking is layered through the following questions:

- How do educational policy texts effect the practice of each artist?

- How can rhizomatic thought be used to analyse the themes within our data?

- How can following our lines of flight provide new opportunities for policy discourse and connect our collective practices across policy texts?

Methodological choices

This paper focuses on the experiences of five artist educators involved in a project. Two colleagues in Iceland and one in the United Kingdom were initially primary school teachers, now arts researchers and lecturers in universities, with specialisms in drama. One colleague in Greece worked for a non-profit organisation inspiring future education through a range of creativity and social change projects, and one colleague in Berlin was an experienced artist educator working in between community and school settings. Collectively, all five artist educators’ work is concerned with drama, visual arts in both formal and non-formal education. As educators we are not solely school based offering an outward facing perspective.

During 18 months of the Erasmus+ project, we systematically explored and compared our experiences through online eleven discussion, presentations, and live practices. We each reflected on the following three methodological questions:

- What is the educational policy context in your country in relation to creative arts in education?

- What is the policy issue that you would like to address in relation to creative arts learning?

- How have you used your artistic practice to mediate/respond to policy?

Whilst the first question was concerned with recounting the policy context as the first layer of the story constellation, the second and third questions required us to draw from critical incidents in our practice, both pedagogical and artistic, in relation to policy. Our view was that layering our narrative in this way would illuminate our practice in relation to our differing contexts and policy texts.

“Story Constellation” as method

Rhizo-textual methods and analysis (Honan, 2015) often drawn from various and contradictory work, ideas and concepts in order to connect fragments of data and make new connections. The researchers acknowledge that whilst narrative inquiry and rhizomatics take differing ontological positions, they are used together in this analysis to illuminate new readings of policy documents and practices through narratives which would otherwise, not be visible. Our critical reflections are offered through “story constellations” (Craig, 2007), a form of narrative inquiry used to illuminate experiences of practice.

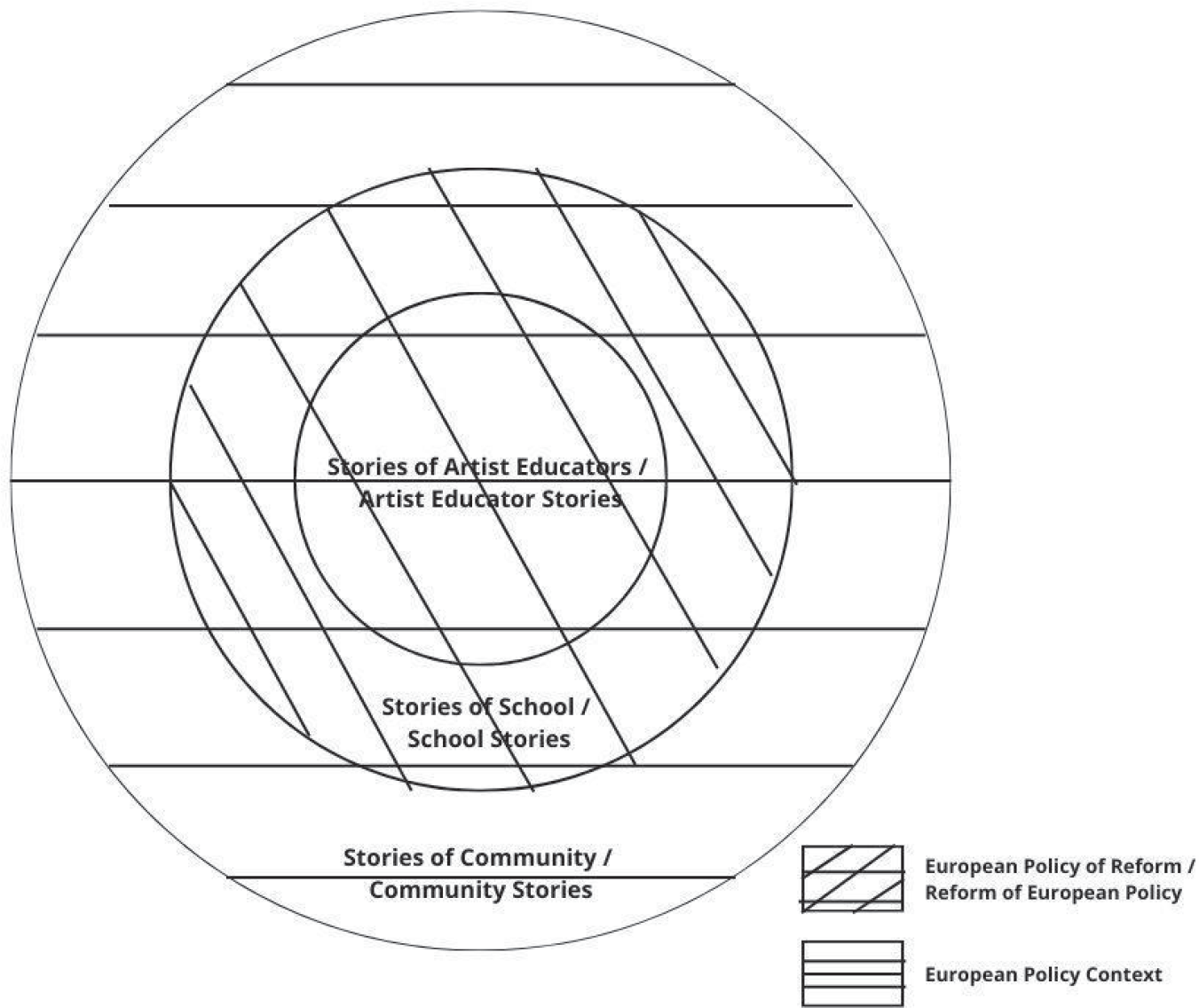

In line with Craig (2007), we view this form of storytelling as a rich source of professional information and knowledge exchange and “acting as a method of interpretation and re-interpretation of experience” (p. 175) which adds depth to our rhizo-textual reading of policy. Whilst this storytelling approach has been used to examine teachers’ experiences of policy reform in context it has not been applied to examining the artist educator’s position in relation to policy. We viewed this narrative approach as a helpful way of mapping the unfolding movement of our hybrid practices in relation to policy texts. Through analysis of our differing narrative patterns, story constellations are seen as a rhizo-textual method from which we illuminate our movement, within differing policy contexts. Whilst our constellations are not visual interpretations, we view them as rhizomatic cartographies which highlight the interplay between policy (macro level), the practice of schools and communities on a (meso level) and the artist educator pedagogy on a (micro level).

Rhizo-textual Analysis

We draw from the term “burrowing” (Connelly & Clandinin, 1990) which refers to the collaborative reflective approach taken to analysis, ensuring trustworthiness and transparency. Our stories were exchanged, and we critically reflected on each other’s stories in relation to our own, drawing out similarities and differences. In line with Deleuzian thought, we were interested in developing more heterogenous understanding of the relationship between our policy narratives and policy texts. Following the sharing of practices, we used descriptive and inferential thematic coding (Miles & Huberman, 1994) to map our collective pedagogical features within differing policy contexts in which we work. This cartography highlights our “lines of flight,” or spaces in which we made new connections and movements. These mappings were cross referenced across each of the four reflections.

Story Constellations

The following four cartographies are presented through story constellations from each country.

1. Story Constellation Berlin1

Policy context: Culture and education policy in Germany functions within federalist structures. According to Article 30 of the Basic Law, responsibility for culture and education lies with the federal states. Cultural education is a cross-sectional task that is regulated differently from state to state. The legal framework is divided between school, cultural and youth policy. This results in a complex system of structures and responsibilities. In Germany, the term “cultural education” has become established for the various artistic and creative activities inside and outside school. Artistic education in schools takes place in addition to the subjects of art, music and (sometimes theatre). In addition, cooperation with non-school partners such as museums, theatres, orchestras, and individual artists plays a significant role. Although in cultural policy, there is no legal definition of cultural education at the federal level. In the report of the Enquete Commission of the Bundestag “Culture in Germany” in recent years, impulses for the further development and establishment of cultural education in schools have been provided by nationwide funding programs and model projects such as “Kultur macht Schule” (2004–2007) and “Kultur macht stark” (2018–2022). The political goals of a German government are implemented at the state level and thus vary widely across Germany. In Berlin, cooperation between child and youth welfare institutions and schools in the arts is less pronounced.

The unstable structure of funding initiatives that hold space for social and cultural education keeps such practices of reflective, progressive education models in the margins. This attempt prevents established foundations and networks from sharing their experiences constantly within the school system. Every two years KontextSchule, a tandem/team further training program for 12 teachers and 12 artists in Berlin, awaits late notification from the Berlin Senate to hear if the projects may continue or not. With the recent change of leadership in Germany, some projects have been hit harder than others notably, queer education initiatives have been among those most affected. i-PÄD had their funding completely cut and Queer@school and Queer History Month had their budget severely cut (Jürgens, 2022), posing huge questions around longevity and young people’s arts opportunities (Akın & Schirmer, n.d.).

Artist response: An example of our federally funded arts education project is mitkolletiv, which was funded by Berlin Project Fund for Arts Education from July 2020 to July 2021. It is a group of artists and educators who work through an intersectional and antiracist lens to disrupt and intervene in traditional models of education. The collective perspectives are shaped by the affinities and experiences we hold in the group: Black and PoC, queer, non-binary, immigrant, and with varying class and gender identities. Mitkolletiv continues to offer project weeks in schools, after school clubs, teacher training, and workshops at universities, all offering creative methods and power critical methods of learning together.

The project set out to establish a network of arts educators and teachers that are working with the school systems of Berlin who put welfare, creativity, and marginalised perspectives at the centre of their work. Mitkolletiv developed toolkits for artist educators and teachers alike to share knowledge, strategies, and experience from working creatively in schools. Strengthening links between existing intersectional education practices and creative initiatives is a crucial element of the network and toolkits developed. Thus, enabling existing expertise and resources to be shared as well as co-creating new methods and material. Exchange is central to the collective process with multiple art forms and praxis alongside pedagogical frameworks, all feeding into collective knowledge. How the collective worked together was strongly prioritized with all decisions made at collective meetings. The pedagogy foregrounded critical intersectional pedagogies, knowledge exchange of ideas and shared learning in brave spaces (Palfrey, 2017). This included creating physical spaces for exchange, time to share ideas or strategies, working without the pressure of “outputs” and facilitating exchange and experiment.

Currently, i-PÄD is disputing their funding being pulled and the continuation of mitkolletiv, is left to the individual members to apply for the next funding, among many others, neither project is ensured to continue. Stable long-term funding is crucial for maintaining a sustained pedagogy as a practice of resistance.

2. Story Constellation United Kingdom

Policy context: Within the United Kingdom, the expressive arts (drama, art, music, film, design technology, poetry, and dance) are a compulsory part of centralised National Curriculum Policy from the Department of Education (DfE, 2014). There are also regional policy variations within the United Kingdom in relation to the value placed on the creative arts within the curriculum, creating a fragmented policy landscape. Wales, Scotland, England, and Northern Ireland all have different National Curriculum Policy. The Scottish, Irish and Welsh Curriculum have a much stronger focus on the creative arts than the English National Curriculum (2014), which by comparison is narrower and more prescriptive and with the focus on testing and accountability which has aggressively hijacked the creative arts discourse (Wyse, 2015).

This lack of focus on the arts and creativity in England is marked by a massive decline in arts teaching in secondary schools with a focus on core academic subjects. Drama and music have also been removed as a Baccalaureate subject in secondary school at GCSE examination. Furthermore, there has been a sharp decline in art examinations at GCSE and A-level examinations. Many schools do not have funding for after school clubs and curriculum varies from school to school. Drama has been moved into various places within the English Primary National Curriculum from creative arts to English. The English policy context places little value on the creative arts and the national curriculum provides minimal guidance compared to other subject areas. Where there is guidance, an overpacked curriculum and pressures of accountability and testing often limit curricula engagement. Consequently, there is a lack of creative arts expertise and teacher confidence in schools (Cremin et al., 2009) and pre-service teacher training programmes. In stark contrast, Wales has a new National Curriculum launched in September 2022, which has an explicit focus on embedding the expressive arts and creativity across all age’s phases by 2026. This curriculum is placing renewed emphasis on developing assessment competence and supporting schools to plan a creative arts rich curriculum.

Historically, education in the United Kingdom was regarded as notable for its creative pedagogy and curriculum approaches. Between 2002 and 2011, the government’s Creative Partnerships initiative in England was a much-needed commitment to creativity in response to teachers’ concern to an oversubscribed curriculum. Research during this initiative distinguished between creative teaching and teaching for creativity (Craft et al., 2006), the first being new, innovative ways of teaching, the second referring to pedagogies and activities aimed at enhancing the creative thinking and outputs of pupils. Despite this progress, funding for these initiatives was axed overnight by following governments in 2011 and has remained stagnant and narrow.

Currently, the lack of equitable arts and cultural education for young people in England has been described as a “social justice issue” (Paul Hamlyn Foundation and Cultural Learning Alliance, 2019) linking arts education to social mobility. This was backed by the Durham Commission on Creativity in Education (James et al., 2019), which has called for more research into creativity and recognition of creativity in education. The Arts Council England is a non-departmental public body or bridge organisation, responsible for distributing lottery funding to artists and cultural organisations. In, their recent consultation report Shaping the Next 10 Years 2020–30, the Arts Council England calls for opportunities for all, advocating the creation of cultural local communities and further recognition of the links between creative learning and well being.

Artist educator response: In 2017, we established Story Makers Company, a research-practice centre at a University in England with artist educators, researchers, and teachers, collectively focusing on empirical based research into creative pedagogies (Stephenson, 2023; Stephenson et al., 2022). For many children, the spaces for bringing their lived experiences and social imagination into the English curriculum are being squeezed by policy and economic circumstances. Pedagogically, the research and practice focus on creating brave spaces through story which empower young people to see themselves as changemakers. This feeds into teacher and artist professional development and pre-service teacher education, however it too is set against the restrictions of working within an institution such as lack of funding and time.

Tahirsylaj and Sundberg (2020) state that there is still unfinished business for educational researchers in critically engaging with framing and defining competences for the twenty-first century, their causes, impact and consequences for schooling and learning internationally. Cremin and Chappell (2019) also highlight methodological and empirical gaps in research which foregrounds learners’ perceptions of creative learning. Recent PhD research (Stephenson, 2022) explored children’s engagement within drama. The research revealed a set of 8 wellbeing and creativity dispositions and transferable competencies which articulated children’s perceptions of learning over time. Creativity and wellbeing were evidenced through increased socio-emotional literacy and collective action, offering a competency assessment tool for teachers to use recognise and evidence creative learning within the classroom (Stephenson, 2023).

3. Story Constellation Greece

Policy context: The last few years arts education in schools has been marginalized (with art classes and sociology excluded from Upper Secondary Education); together with humanities and social studies, they are viewed as low priority subjects in the Greek school curriculum (Choleva et al., 2021). This is explained by the fact that these subjects are not considered a way for students to enter the job market (Marouli & Duroy, 2019), unlike others. The long-lasting economic crisis in Greece and the pandemic had a negative effect on the educational system with literature supporting that the crisis had a severe impact on education structures, reporting teacher shortages for music subjects in Music Schools (Vergeti & Giouroglou, 2018). Also, despite the recent enrichment of the all-day school curriculum with art and drama classes (IEP, 2016), art teacher shortages are also being reported in all-day schools (IEP, 2018). Additionally, demonstrations took place in 2022, from students at Artistic Secondary Education Schools, due to the huge bureaucratic burden for art educators working in schools and delay of annual programming.

Every academic year the Institute of Educational Policy in Greece (2021–2022) publishes a curriculum guide on how subjects including arts, music and drama should be taught across educational levels. Regarding arts education, teachers are expected to select the teaching material depending on the time available, the characteristics of the student potential, and the overall and annual planning. Arts education is an open subject, not strictly tied to the curriculum and it is offered to primary and lower secondary school (ages 13–15). As for drama education, it is offered only at primary school level. The curriculum guide points out that emphasis should be placed on teamwork, as no one can experience drama individually. Learners should be encouraged to express themselves, act, and manifest with proposed activities like body and language release, theatre codes’ teaching, improvisation, mask making, marionettes and shadow theatre. Despite these specific instructions on how to address drama education in primary school, current literature underlines the urgent need to provide art educators with lifelong training which they lack compared to other educators in Greece (Pavlou et al., 2021). As far as music education is concerned, it is offered to learners from the kindergarten up to gymnasium and it includes instruction in the basic elements of music, types of music, the connection of music with other arts and sciences, and the study of music in life inside and outside school. The teaching methodologies to be implemented in music education are collaborative, interdisciplinary, and experiential learning linking to all subjects, pupil needs and interests (Kokkidou et al., 2021).

The latest socio-economic conditions in Greece have led to the emergence of new arts, music, and drama education initiatives, for example, in the framework of the refugee crisis in Greece, some new educational activities have emerged suggesting the implementation of arts curricula (Escaño et al., 2021). Also, there is a growing interest in the value of teachers using drama pedagogy to support the refugee crisis at a university level (Choleva et al., 2021).

Artist educator response: The challenge that we want to address is focused on addressing misconceptions of the importance of the artistic and creatives’ profession, as not enough time and effort is invested in this sector, especially within school contexts. When it is not considered a priority, it is implied that it is not considered as a career option nor as an economic, well being, value-generating factor, therefore not included in national school curricula. Through transnational projects with EU, we design inter-disciplinary educational material that corresponds directly to the heart of the problem in Greek schools: using art to reach competences’ goals, teaching other majors through art and redefining art’s impact on education and community. To achieve that, we are working constantly with creative professionals to enrich citizenship, environmental, entrepreneurial and changemakers’ education. Following impact assessment methodologies, we evaluate this process every step of the way and it is proven that students integrate knowledge and information better through creative processes. Indicative projects are the Creatives Academy project through which we introduce the culture and creative sector as a career option through encounters and project-based activities with creative professionals; the Green EduLARP project 2, using live action role playing for environmental education; SCIL project, where we cooperate with an international digital art festival to enhance citizenship education through digital art in schools.

4. Story Constellation Iceland

Policy Context: The education policy that appears in The Icelandic National Curriculum Guide is based on six fundamental pillars on which the curriculum guidelines are based. The six fundamental pillars of education and the emphases of the Compulsory School Act (The Ministry of Education, Science and Culture, 2014) are intended as guidelines for general education and work methods of compulsory school. The fundamental pillars are literacy in the widest sense, education towards sustainability, health and welfare, democracy and human rights, equality, and creativity. The fundamental pillars appear in the content of subjects and subject areas, the students’ competences, study assessment, school curriculum guide and the internal evaluation of schools. All the fundamental pillars are based on critical thinking, reflection, scientific attitudes, and democratic values. The fundamental pillars refer to social, cultural, environmental, and ecological literacy so that children and youth may develop mentally and physically, thrive in society, and cooperate with others. In evaluating school activities, the influence of the fundamental pillars on teaching, play as studies must be taken into consideration (The Ministry of Education, Science and Culture, 2014).

The Icelandic National Curriculum Guide (2014) for compulsory education (grades 1–10, children ages 6 to 16 years), highlights arts and crafts. They are divided on the one hand into performing arts (dance and drama), visual arts and music, and crafts, on the other, which includes home economics, design, and craft and textiles. Arts and crafts are so intertwined in our everyday lives that we are often unaware of their existence and influence. The yield from arts and crafts is not limited to artistic events, exhibitions, and workshops, for our whole environment and daily life are shaped by arts and crafts. The main objective of arts and crafts in compulsory schools is for every pupil to use a variety of work methods that involve artisanship, creativity, the integration of intellect and feelings and several different forms of expression. The timetable for arts and crafts should account for around 15% of the weekly classes. Every school decides if the subjects are taught separately or integrated in separate short-term courses that are allocated more hours in the timetable during certain periods or continuously throughout the school year (Österlind et al., 2016).

Artist educator response: We have focused on bringing drama into the classroom. Drama as a subject is brought to the site as a traveller from the arts, with a basis in theatre. To make the traveller an inhabitant of the educational space, the ecologies of practice need to adjust to a new balance in the educational system. According to the curriculum, drama education should train students in the methods of the art form, but no less in dramatic literacy in the widest sense of the term, that is, by enriching and facilitating the students’ understanding of themselves, human nature, and society (Thorkelsdóttir, 2016). In drama students are to have the opportunity to put themselves in the position of others and experiment with different expression forms, behaviour, and solutions in a secure school environment. Drama encourages students to express, form and present their ideas and feelings. In addition, drama constantly tests cooperation, relationships, creativity, language, expression, critical thinking, physical exertion, and voice projection. This is all done through play and creation (Ministry of Education, Science and Culture, 2014, p. 153). The competence criteria for drama in the Icelandic National Curriculum Guide also provide aims for drama as a teaching method, where the teaching methods are grounded on the art form itself. The competence criteria for drama in grade 4 are process-based, whereas for grade 7 and 10, lessons in drama are theatre-based, and drama aims towards the product field.

In considering ways to prepare initial teacher educators in drama, research from Thorkelsdottir (2016) found that drama teachers consider heavy workload and lack of time as the most difficult part of teaching. They also must teach drama as a whole class activity teaching up to 50 students at a time. Teachers also talk about the need for communication with other teachers, and this lack of community creates feelings of isolation. But what matters the most is not having a proper space for drama like a drama studio, or at least a room suitable for drama to teach in (Thorkelsdóttir, 2018). All the arts and craft subjects in Icelandic schools have their own space to teach in, except drama. Because drama instruction is a newcomer in the curriculum, in some schools’ drama teachers are faced with the additional problem of having no classroom to teach in. That problem is a political matter (Thorkelsdóttir, 2016). If the principal is in favour of drama, he or she will both make the space for drama and invest in the subject. The main reason for drama teachers leaving the profession is often poor working conditions, personal stress, anxiety, and lack of trust. But drama and theatre education are important in schools, giving all students the opportunity to take part in a “What if” world regardless of the social class they belong to. In a constantly changing world where technology is developing rapidly, drama has something to offer other subjects do not have, because it gives us the opportunity to imagine and enact futures and try out ideas (Thorkelsdóttir et al., 2022).

Emerging themes and discussions

Rather than a linear reading of policy texts, the rhizo-textual analysis from each artist reveals a social critique of the educational landscape through vibrant policy narratives. It is clear to see through each story constellation, the ways in which the artist educator’s practice adapted in response to the specific policy, socio-political and economic challenges in each country.

In Greece, a lack of focus on creative arts in educational policy is accompanied by a declining job market, teacher shortage and a lack of training and research in creative arts. In this story constellation, the work of the artist educator recounted addressing social justice issues such as the refugee crisis and climate change through creative education and practice. This involved creating spaces of inclusion and social action through the creative arts. Pedagogy is seen as responding to these problems in new and hybrid ways. In Germany, cultural education has also been hit by funding cuts, marginalising opportunities for creative arts education and opportunities. The practice shared in this story constellation is seen as disrupting traditional models of education, responding to lack of voice, particularly in relation to LGBTQ identity, making meaningful links to intersectionality through drama and creative arts pedagogy. This pedagogy involved creating new spaces of inclusion and social action through the arts. In England, narrow education policy was also seen to marginalize opportunities for the creative arts in schools and communities, this was set against an acute rise in young peoples’ mental health, funding cuts and issues with primary teachers’ knowledge and confidence regarding creative arts. The practice-based research shared in this story constellation spoke of creating hybrid curriculum spaces for creative arts which focused on amplifying pupil voice, equity, diversity and wellbeing through drama pedagogy. The policy landscape in Iceland was much more progressive than the comparative countries, actively valuing creative arts as a more focused aspect of standardised curriculum. The artist educators in this story constellation, however, still used their pedagogy and research, to seek out new spaces for drama in response to teacher engagement problems, stress, and poor working spaces.

Pedagogy as a brave resistance space

Through rhizo-textual reading in each of the stories, creative practice and pedagogy was collectively defined by hybridity and rhizomatic movement in order to create and hold spaces of resistance to unwanted policy change.

This process was underpinned by ethics of inclusion and equity. In line with Ali (2017), our practice created brave spaces for diverse learners to express themselves through collective action. As artist educators, we too needed to occupy brave spaces. Our practices produced change, by providing new opportunities for creative engagement. Change was related to agentic, professional action which resists policy restrictions. Our positioning of practice often highlighted contradictory policy discourses, in terms of equitable learning. Thus, the reading of policy texts was altered or challenged through the pedagogic responses of the artist educator. Collectively, our line of flight highlights rhizomatic movement which was always underpinned and foregrounded by ethical principles of practice. Put differently, our ethical principles drove our collective actions as professionals within differing policy texts.

Rhizomatic practices took different forms of activism and change making across all countries: In Germany, UK, and Greece the resistance spaces centred on amplifying marginalised perspectives, changing the resources available and access to the arts education in relation to policy. In Iceland and Germany, the practice focused on creating new networks and addressing poor working conditions through their practices. Collectively, our pedagogical movement within differing policy contexts demonstrated a commitment to strengthening the intersectional links between wellbeing, critical agency, creativity and education, even when these were marginalised within policy. We term these pedagogical movements as resistance spaces because we were responsive to the restrictive policy landscape in our own countries in differing ways by seeking out new equitable spaces and openings for creative learning.

Ideologies of creative practice

Returning to our research questions, it is clear from our story constellations as artist educators that rhizomatic thinking underpinned a sense of agentic movements against the dominant policy narrative seeking out new positions as policy actors. The thematic mapping of these actions through story constellations revealed ten collective characteristics underpinned by shared ethical principles and ideologies of creativity.

- Disrupting traditional models of education

- Responding to contemporary landscape and issues

- Changing practice/spaces/pedagogy/policy landscapes

- Supporting and connecting teachers, children, communities

- Amplifying youth agency and voice

- Addressing issues of social justice/social problems

- Moving to new places of possibility

- Foregrounding values based relational learning

- Activating collective creativity

- Co-creating new practices

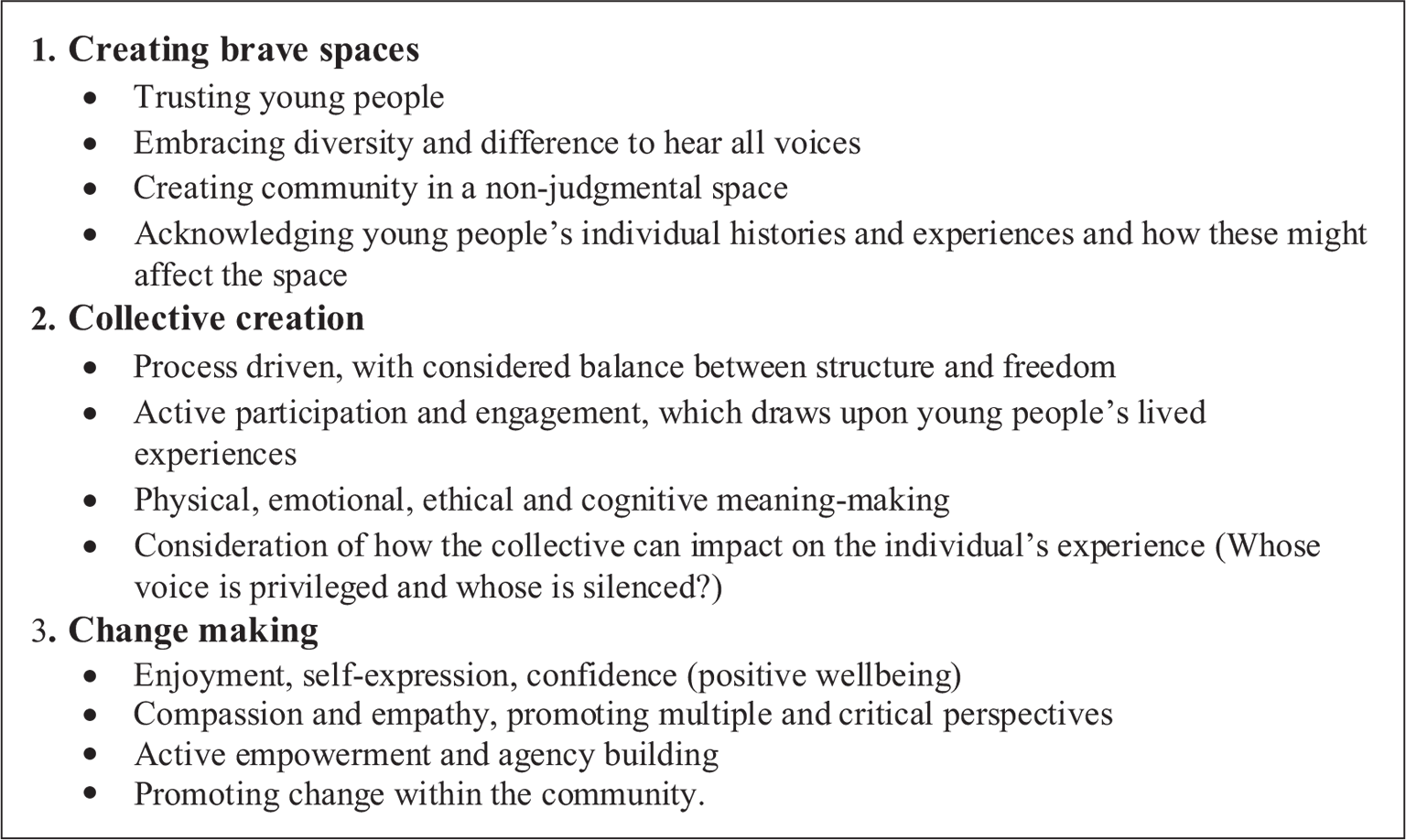

Through analysis of both our policy narratives and following practical workshops, we have created a further ethics of practice framework (Figure 2) In line with Deleuze and Guattari, (2004), our rhizomatic movement has produced something new, “an assemblage.” This co-creation will shape the co-created research and intellectual outputs, or pedagogical guides, which we will collectively create for teachers, teacher educators and parents within this project. These collective ethical principles place value on relational aspects of learning, such as space, affect and connection. This means that whilst each artist stimulus, created by differing artists across countries, may vary according to artist form (music, drama or creative writing etc.) and policy text, the pedagogy within the guides will maintain a shared ethics of practice connecting the work. Whilst we recognise that many artist educators may already enact these ethics, policy texts do not foreground these ethics of practice risking marginalisation of relational learning for children, parents and teachers in education. The aim is that these resources also hold “mediation” spaces for equitable practices and wellbeing to sit through creative arts pedagogy. In this sense our intellectual outputs also act as resistance spaces, bringing arts education back into policy texts.

Discussions: Creative pedagogy and criticality

Theoretically, this paper aims to promote wider discussions about the implications of using Deleuzoguattarian theory to read policy texts in education, offering a unique contribution about reading policy differently through artist-educators. Whilst policy writers assume policy compliance, our rhizo-textual analysis of artist educator’s practice has shown to challenge the perceived lack of professional agency afforded within educational policy texts. Through cartography, new pedagogical connections were illuminated and strengthened through activism. Creative pedagogies were seen to disrupt the relationship between policy on a macro level and the learner on a meso and micro level – providing a sense of professional agency, grounded within an ethics of practices. This suggests that creative pedagogy has the potential to become a critical tool for teachers and policy makers to perform their complex relationship with curriculum in new ways, through policy actions which foreground ethics and professional agency (Stephenson, 2023)

In thinking about the importance of creative arts pedagogy, often disregarded in education because it is difficult to measure, we argue that the ten characteristics of our pedagogy are also critical wellbeing competencies for young people and teachers in becoming adaptable and resilient in a changing world. This warrants further research. With this in mind, we raise questions about why arts education and cultural learning is not more of a priority, as seen through the Icelandic curriculum. As artist educators, we continue to seek out resistance spaces for creative pedagogies when many policies and political structures are defunding such projects and initiatives.

Acknowledgement

The project was funded by Erasmus plus.

References

- Akın, G. & Schirmer, C. (n.d.). i-PÄD (@ipaed.Berlin) Instagram photos and videos. https://www.instagram.com/p/CWITd92qAQ6/

- Ali, D. (2017). Safe spaces and brave spaces. NASPA Research and Policy Institute, 2, 1–13.

- Arday, J. (2019). The black curriculum: Black British history in the national curriculum report. The Black Curriculum.

- Arts Council England. (2019). Shaping the next 10 years. Draft strategy for consultation. https://www.artscouncil.org.uk/sites/default/files/download-file/Draft_Strategy_summer_consultation_2019.pdf

- Avvisati, F., Jacotin, G., & Vincent-Lancrin, S., (2013). Educating higher education students for innovative economies: What international data tell us. Tuning Journal for Higher Education, 1(1), 223–240. https://doi.org/10.18543/tjhe-1(1)-2013pp223-240

- Ball, S.J., Maguire, M., Braun, A., & Hoskins, K. (2011). Policy actors: Doing policy work in schools. Discourse: Studies in the Cultural Politics of Education, 32(4), 625–639. https://doi.org/10.1080/01596306.2011.601565

- Banaji, S., Cranmer, S., & Perrotta, C., (2013). What’s stopping us? Barriers to creativity and innovation in schooling across Europe. In K. Thomas & J. Chan (Eds.), Handbook of research on creativity (pp. 450–463). Edward Elgar Publishing.

- Bansel, P. (2015). A narrative approach to policy analysis. In K. N. Gulson, M. Clarke, & E. Bendix Petersen (Eds.), Education policy and contemporary theory: Implications for research (pp. 183–194). Routledge.

- Bath, N., Daubney, A., Mackrill, D., & Spruce, G. (2020). The declining place of music education in schools in England. Children & Society, 34(5), 443–457. https://doi.org/10.1111/chso.12386

- Cahill, H., Aitken, V., & Hatton, C., (2018). We need to talk about theory: Rethinking the theory/practice dichotomy in pursuit of rigour in drama research. In P. Duffy, C. Hatton, & R. Sallis (Eds.), Drama research methods: Provocations of practice (pp. 183–199). Brill.

- Carrillo, C., & Baguley, M., (2011). From schoolteacher to university lecturer: Illuminating the journey from the classroom to the university for two arts educators. Teaching and Teacher Education, 27(1), 62–72. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tate.2010.07.003

- Choleva, N., Lenakakis, A., & Pigkou-Repousi, M. (2021). Teaching human rights through educational drama: How difficult can it be? A quantitative research with in-service teachers in Greece. In Proceedings of the 2nd World Conference on Research in Social Sciences (pp. 75–89). Diamond Scientific Publishing. http://10.33422/2nd.socialsciencesconf.2021.03.25

- Clandinin, D. J. (2006). Narrative inquiry: A methodology for studying lived experience. Research Studies in Music Education, 27(1), 44–54.

- Connelly, F. M., & Clandinin, D. J. (1990). Stories of experience and narrative inquiry. Educational Researcher, 19(5), 2–14. https://doi.org/10.3102/0013189X019005002

- Connelly, F. M. & Clandinin, D. J. (2012). Narrative inquiry. In J. L. Green, G. Camilli, P. B. Elmore, A. Skukauskaiti, & E. Grace (Eds.), Handbook of complementary methods in education research (pp. 477–487). Routledge.

- Craft, A., Cremin, T., Burnard, P., & Chappell, K. (2006). Progression in creative learning. Arts Council England, Creative Partnerships.

- Cowburn, A., & Blow, M. (2017). Wise up: Prioritising wellbeing in schools (Report). Young Minds and National Children’s Bureau.

- Cremin, T., & Chappell, K., (2019). Creative pedagogies: A systematic review. Research Papers in Education, 36(3), 299–331. https://doi.org/10.1080/02671522.2019.1677757

- Cremin, T., Barnes, J., and Scoffham, S., (2009). Creative teaching for tomorrow: Fostering a creative state of mind deal. Future Creative.

- Cultural Alliance & Hamlyn, P. (2019). The arts for every child: Why arts education is a social justice issue? https://culturallearningalliance.org.uk/wp-content/uploads/2019/10/Arts-for-every-child-CLA-Social-justice-briefing.pdf

- Deleuze, G., & Guattari, F. (2004). EPZ thousand plateaus. A&C Black.

- Deleuze, G., & Guattari, F. (1987). A thousand plateaus. (B. Massumi, Trans.) University of Minnesota Press. (Original work published 1980)

- Department For Education. (2014). The National Curriculum Framework Document 2014. DfE.

- Dobson, T. and Stephenson, L. (2022). A trans-European perspective on how artists can support teachers, parents and carers to engage with young people in the creative arts. Children & Society, 36(6), pp. 1336–1350. https://doi.org/10.1111/chso.12580

- Escaño, C., Mesías-Lema, J. M., & Mañero, J. (2022). Empowerment of the refugee migrant community through a cooperation project on art education in Greece. Development in Practice, 32(7), 912–927. https://doi.org/10.1080/09614524.2021.1944986

- Facione, P. A. (2011). Critical thinking: What it is and why it counts. Insight Assessment, 1(1), 1–23.

- IEP. (2016). “Experts’ Reports”, report prepared by the IEP and academic experts for the OECD review team. IEP.

- Holochwost, S. J., Wolf, D. P., Fisher, K. R., O’Grady, K., & Gagnier, K. M. (2018). The arts and socioemotional development: Evaluating a new mandate for arts education. In R. S. Rajan, & I. C. O’Neal (Eds.), Arts evaluation and assessment: Measuring impact in schools and communities (pp. 147–180). Springer.

- Honan, E. (2007). Writing a rhizome: An (im)plausible methodology. International Journal of Qualitative Studies in Education, 20(5), 531–546.

- Honan, E., & Sellers, M. (2008). (E)merging methodologies: Putting rhizomes to work. In I. Semetsky (Ed.), Nomadic Education (pp. 111–128). Brill.

- Honan, E. (2015). Thinking rhizomatically: Using Deleuze in education policy contexts. In K. N. Gulson, M. Clarke, & E. B. Petersen (Eds.), Education policy and contemporary theory (pp. 208–218). Routledge.

- James, S. J., Houston, A., Newton, L., Daniels, S., Morgan, N., Coho, W., … & Lucas, B. (2019). Durham commission on creativity and education. https://www.dur.ac.uk/resources/creativitycommission/DurhamReport.pdf

- Jürgens, J. (2022, 30 March). Kürzungen im Berliner Haushalt: Kein Geld für queere Bildung. Die Tageszeitung. https://taz.de/!5844456/

- Kokkidou, M., Kondylidou, A., & Mygdanis, Y. (2021). Music curricula of Greece, Sweden, and Japan: Comparative study and reflections. Multilingual Academic Journal of Education and Social Sciences, 9(1), pp. 176–196. http://dx.doi.org/10.46886/MAJESS/v9-i1/7364

- Marouli, C., & Duroy, Q. (2019). Reflections on the transformative power of environmental education in contemporary societies: Experience from two college courses in Greece and the USA. Sustainability, 11(22), 6465. https://doi.org/10.3390/su11226465

- Miles, M. B., & Huberman, A. M. (1994). Qualitative data analysis: An expanded sourcebook. Sage.

- Ministry of Education, Science and Culture. (2014). The Icelandic National Curriculum Guide for compulsory schools – with subjects areas.

- Palfrey, J. (2017). Safe spaces, brave spaces: Diversity and free expression in education. mit Press.

- Pavlou, V., Anagnou, E., & Fragkoulis, I. (2021). Towards professional development: Training needs assessment of primary school theater teachers in Greece. Education Quarterly Reviews, 4(1).

- Sheridan-Rabideau, M. (2010). Creativity repositioned. Arts Education Policy Review, 111(2), 54–58. https://doi.org/10.1080/10632910903455876

- Stephenson, L. (2023). Collective creativity and wellbeing dispositions: Children’s perceptions of learning through drama. Thinking Skills and Creativity, 47, 101188. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tsc.2022.101188

- Stephenson, L., & Dobson, T., (2020). Releasing the socio-imagination: Children’s voices on creativity, capability, and mental well-being. Support for Learning, 35(4), 454–472. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-9604.12326

- Stephenson, L., Daniel, A., & Storey, V., (2022). Weaving critical hope: Story making with artists and children through troubled times. Literacy, 56(1), 73–85. https://doi.org/10.1111/lit.12272

- Stephenson, L. (2022). Rewilding the curriculum through drama: Creative–critical thinking in the primary classroom. Meta-affective stories of creativity–struggle–wellbeing–hope [Doctoral dissertation].

- Tamboukou, M. (2014). Charting cartographies of resistance: Lines of flight in women artists’ narratives. Gender and Education, 22(6), 679–696. https://doi.org/10.1080/09540253.2010.519604

- Thorkelsdóttir, R. (2016). Understanding drama teaching in compulsory education in Iceland: A micro-ethnographic study of the practices of two drama teachers [Doctoral dissertation, Norwegian University of Science and Technology]. NTNU Open. http://hdl.handle.net/11250/2411642

- Thorkelsdóttir, R. B. (2022). What are the enabling and what are the constraining aspects of the subject of drama in Icelandic compulsory education? In X. Du, & T. Chemi (Eds.), Arts-based methods in education around the world (pp. 231–246). River Publishers.

- Þorkelsdóttir, R. B., & Jónsdóttir, J. G. (2022). Performative inquiry: To enhance language learning. In L. Krogh, A. Scholkmann, & T. Chemi (Eds.), Performance and Performativity (8 ed., Vol. IV, pp. 43–63). (The Pedagogy of the Moment: Building Artistic Time-Spaces for Critical-Creative Learning in Higher Education; Vol. IV, No. 8). Aalborg University Press.

- Vergeti, M., & Giouroglou, C. (2018). CH, education and financial crisis: The case of Greece. Open Journal for Sociological Studies, 2(1), 1–12. https://doi.org/10.32591/coas.ojss.0201.01001v

- Wyse, D., & Ferrari, A. (2015). Creativity and education: Comparing the national curricula of the states of the European Union and the United Kingdom. British Educational Research Journal, 41(1), 30–47.

Footnotes

- 1 The Story Constellations refer to different contexts in 2022/21.