Introduction: An ethical itch as the productive agent of a diffractive inquiry

In this article, I am inquiring into an ethical itch that emerged as I was creating a video article about a dance educational research project in a Norwegian public school. Ethical doubts had emerged concerning my own desire to use the video material from dance workshops in the project started to form. The idea of exposing both the pupils and teachers in the project through sometimes vulnerable and intimate moments in an open video article on the internet performed me like an itch. Inspired by the method of performative inquiry (Fels, 2010, 2015), I experienced this itch as a stop-moment, a bodily experience that “interrupted, disrupted, troubled, astonished” (Fels, 2015, p. 511) me. My doubts, my itching, was the body telling me that something of importance was at stake, a disruption that needed inquiring into.

When I talk about performativity, I refer to Austin’s (1975) notion of the concept, further developed by von Hantelmann (2014). To von Hantelmann, performativity separates from a representational “performance-like” (Østern et al., 2021, p. 5) understanding of the notion. In a performative inquiry, I am rather concerned with, for example, what is created as the itching performs my ethical considerations of using the video material from the dance workshops.

Instead of carrying on with the video article, I decided to attend to the itching doubts engaging with a theoretical apparatus that sits within a post-humanist (Braidotti, 2013), performative (Haseman, 2006; Østern et al., 2021), and agential realist approach (Barad, 2007). Through the agential realist approach, Barad (2007) draws attention towards how matter, both human and non-human, entangle with obligation to each other. The ethical doubt is an example of how the video material from the dance project performed me in ways that I could not ignore. Here, I am intra-acting with the research, or touching and being touched (Barad, 2012), rather than observing from a distance.

To Barad (2007), ethics, ontology, and epistemology entangle, or become-with each other, as ethico-onto-epistemology. This coincides with how I perceive the entanglement between choreography, researching, and teaching, and the ethico-onto-epistemological entanglements that emerge from attending to the itch in such an a/r/tographic practice (Le Blanc & Irwin, 2019). Kuby and Zhao (2022), as well as Chappell (2022), stress that what we are doing, our actions are ethical matters of importance. I recognize this, for example, through how my pedagogical values, and the aesthetic values that I am cultivating through my dance practice, are of significance for the ethico-onto-epistemological entanglements that I create in this inquiry. Critically reflecting on these entanglements also informs my in-class pedagogical and artistic choices (Risner & Schupp, 2019). These considerations have led to the two analytical questions giving direction and speed to the inquiry:

What choreographic-pedagogical insights are created through diffracting with an ethical itch emerging from a dance project in elementary school? How can diffractive inquiry perform sense-making in research, choreography, and education?

A dance project about birds and the video camera as a research participant

I have a background as a dance teacher, choreographer, and dance artist and have over the last decade been engaged in community dance projects. I experience that my practice in these projects lies in between education, choreography, research, and dance, as an a/r/tographic practice (Le Blanc & Irwin, 2019). This means that I am constantly attending to these different aspects and how they relate (Bickel et al., 2011; Irwin, 2004; Irwin et al., 2006; Østern, 2018b) in my practice.

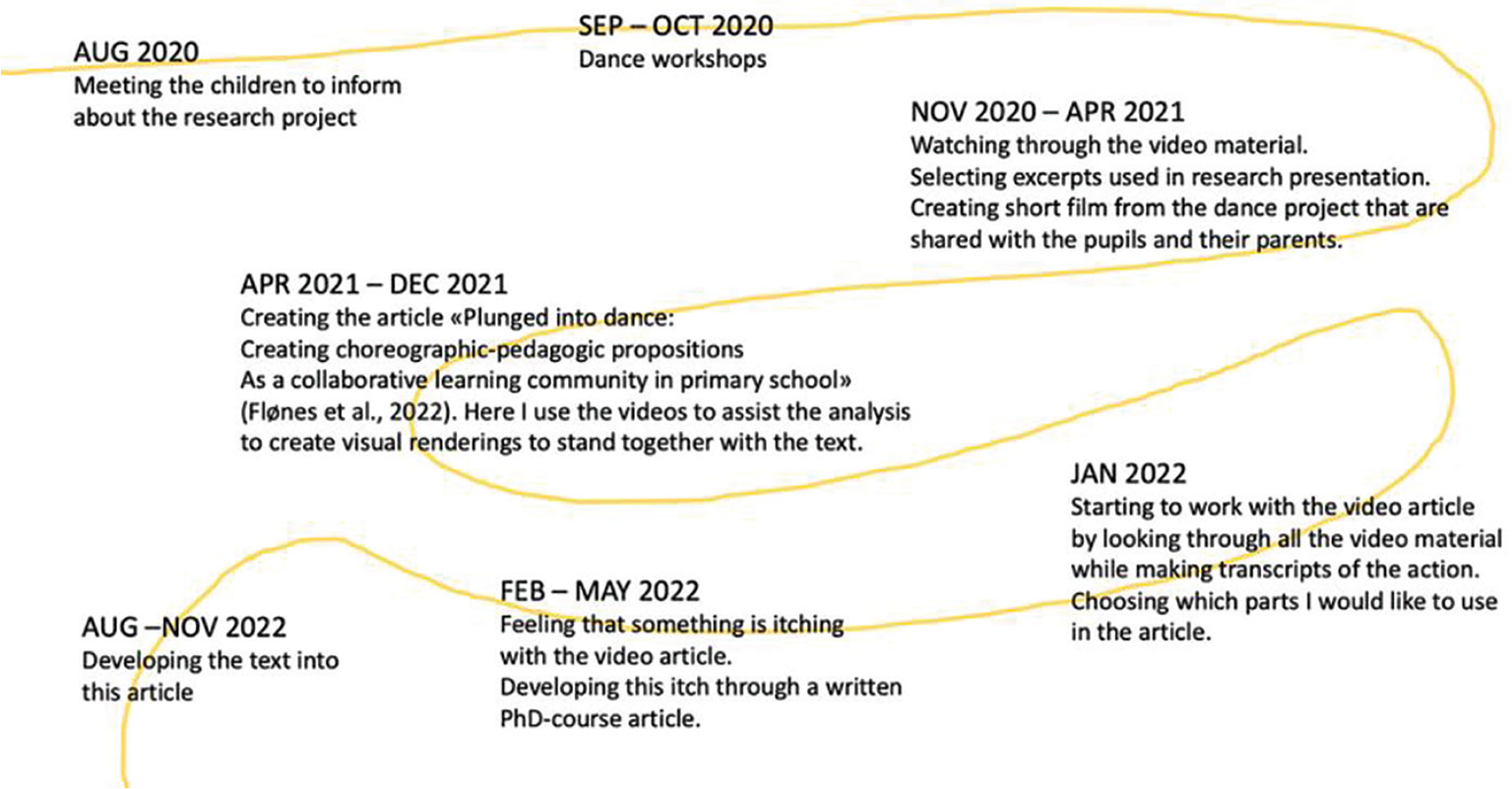

As a part of my PhD project, in the autumn of 2020, I carried out a dance project (Figure 1) as a choreographer-researcher-teacher in an urban school in Norway, together with third graders and their teachers (Flønes et al., 2022). The cooperating school invited me to be one of several visiting artists in the interdisciplinary Bird project. The project aimed to create relations between different teaching subjects such as languages or mathematics and art expressions through the theme of birds.

There were three classes divided into approximately 15 pupils in each class, aged eight years old. A few of the pupils took dance classes after school, but most of them did not have any experience with dance.

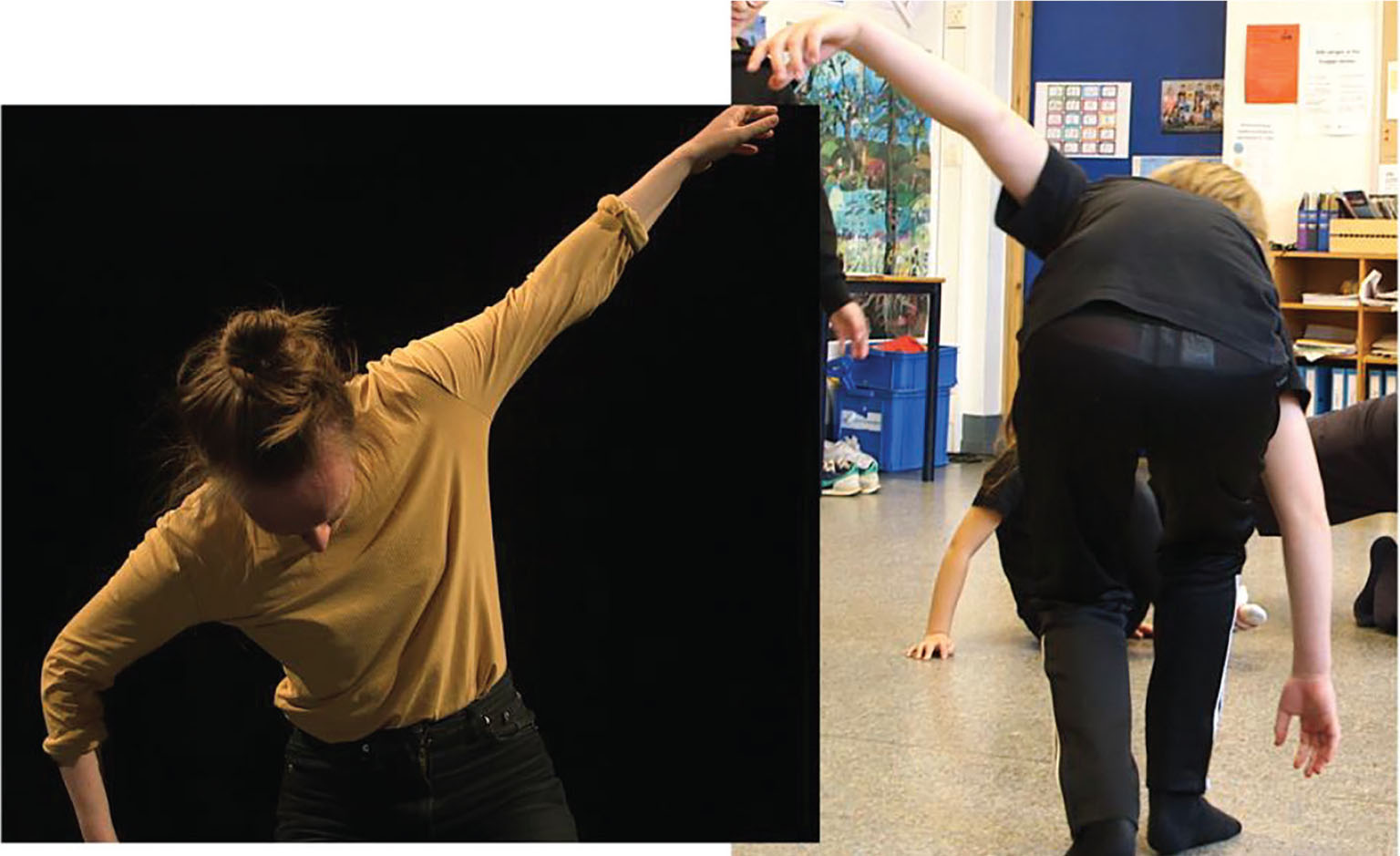

In the dance project, I carried out workshops in creative dance (Gilbert, 2015), working on the theme of birds (see Flønes et al., 2022). In these workshops, my focus was on cultivating the children’s possibility of creating their own dance, or dances, through supporting their process (e.g., Anttila et al., 2019; Anttila & Sansom, 2012; Stinson, 2016; Østern, 2010). With me in the dance workshops was Elisabeth, the video photographer, who documented the research process. She interweaved with the dance project and the three classes, through moving around in the classrooms with her camera. The children, the teachers, and I, allowed her to go sometimes very close to the situations happening, without interrupting what we were doing (Figure 2).

Before the dance project started, the pupils were informed that Elisabeth was going to be present with her camera, and that the video might be used in research presentation. They were also informed that they could reject being filmed.

The video footage and its intra-active potential

After the dance project at the school, I was left with hours of video documentation from Elisabeth, which consisted of a rich and close-to-action material: dialogues, trying out dance movements, all of us performing and sharing dances with each other, struggles, victories, moments of bravery and moments of awkwardness, tears, laughter, euphoria, and questions of wonder. The aesthetic quality of the videos, for example, the sharp images, the camera following the movements in a flowing rhythm, playing with focus and out of focus, made the video material in-between documentation and an artistic rendering (Irwin & Springgay, 2008; Le Blanc & Irwin, 2019; Myers, 2012).

I engaged choreographically with the video material in various ways. When I say choreographically, I refer to the expanded notion of choreography, where choreography is approached as a relational practice that expands the field of dance (Foster, 2010; Klien & Valk, 2007; Manning, 2013). For example, choreographing a short process video shared with the children, their parents, and the teachers was an attempt to create relations between the dance project in school and the parents. I also chose certain situations from the videos and shared them in research presentations where I also danced. In particular, those moments where the children’s dances had evoked euphoria and wonder in both me and the teachers were shared (Flønes et al., 2022). This was a choreographic choice, intending that the videos and my dance engage with the research (Kara, 2020; Pickering & Kara, 2017). I experienced the videos as important aesthetic renderings (Irwin & Springgay, 2008; Myers, 2012) from the dance project, both for myself, fellow researchers, and other audience in order to grasp or get a feel of the project and the research (Pickering & Kara, 2017). This was an important support for my argumentation as to how artists and teachers could cooperate in arts projects in public elementary school. At the time, I found the videos to fairly represent the children (Josselson, 2007). Sharing the videos were a way of acknowledging their contribution to the research.

Thinking with Jackson and Mazzei (2012) and the agential realist approach (Barad, 2007), the videos became a source of material that allowed for intra-action (Barad, 2007) with the dance project. Within agential realism (Barad, 2007), intra-action could be understood through the notion of relational ontology, or onto-epistemology: “an ongoing process in which matter and meaning are co-constituted” (Bozalek & Zembylas, 2017b, p. 65). One example of such a co-constituted process is how I experienced that enthusiasm was becoming-with the meeting between the videos and their different audiences.

In the following, I review existing research, focusing on relational perspectives on ethics in research and research presentation.

The ethics of research presentation and representation of research participants

Pickering and Kara (2017) draw our attention to the fact that little research has been carried out about ethical issues related to research presentation and representing research participants. This coincides with my own search for existing literature on the topic in the context of dance education research. To Pickering and Kara, research presentation is an ethical arena: A relational and affective experience, where participants, researchers, and audience are engaged in the research and with each other. What we choose to foreground in research presentation and how we represent it, I find necessary to discuss.

The ethical itch is a good example of “conflicting – goods” (Pickering & Kara, 2017, p. 300). I have to negotiate my doubts about exposing the children through the videos, and the engagement the videos can trigger in fellow researchers and other audience (Pickering & Kara, 2017). To deal with ethical dilemmas, Pickering and Kara propose an “ethics of engagement” (2017, p. 299, original emphasis), which guides the researcher to “addressing the who, how, who to, and why of representation” (p. 308). In this article, I also address the possibilities that such an approach to ethics can have for a research process.

Ellingson (2017) proposes that an “ethics of representation” (p. 50) comes into play both in traditional publishing formats and when sharing research through artistic expressions, like, for example, dance. According to Ellingson, a central question here is who has the “narrative privilege” (p. 50)? A general assumption in research is that childhood is related to vulnerability (Liamputtong, 2006; Richard et al., 2015; NESH, 2016). But this is also questioned, as Richards et al. (2015) articulate: “While sensitive to the implications of rights to privacy, we want children to remain active participants in research and therefore advocate an approach that regards the two as complimentary rather than oppositional” (pp. 3–4). This quote reveals the nuance between protecting or giving space for expression, both as a challenge and a possibility for creation in research.

Le Blanc and Irwin (2019) question what, for example, arts expressions can do for research presentation, but also as a methodological tool in research. Pickering and Kara (2017) add that “one strength of these more affective approaches is their potential reach” (p. 305, see also Kara, 2020), which resonates well with my experience of sharing the dance videos in research presentations. I would also add that expressions like dance allow me as a researcher to explore new ways of being-with the research (Østern, 2017), for example, as a tool for exploring how I can choreograph with trust (see Foster, 2011 on choreographing empathy). Here, I am referring to how the bodily relations that are created through dancing together have the potential to create trust. How I am dancing and the values that I cultivate through my dance (Risner & Schupp, 2019) are of great importance. Rosenberg (2013) is interested in the relation between ethics, being, and making where “both why we make and the way we make” (p. 1) matter as ethical. This makes me wonder if dancing might attune my body towards the ethical itch in a way that would support my understanding of it.

Ethics as a relational matter of the body

Engaging with ethical doubts is a lived and affective (Massumi, 2002) experience. This guides me towards an embodied perspective on ethics (Pullen & Rhodes, 2015), or what Ellingson (2017) refers to as “ethics of being-with” (p. 46). Moreover, ethics is of choreographic matter through the empathic relations created through, for example, dance (Foster, 2011). I experienced that a strong empathic connection between the children, the teachers and I was created and maintained through dancing together in the dance workshops (see Flønes et al., 2022).

From an a/r/tographic perspective, La Jevic and Springgay (2008) propose an “ethics of embodiment” (p. 68). To them, ethics is about how we relate to other bodies (see also Bickel et al., 2011). We live through “ethical relationships” (La Jevic & Springgay, 2008, p. 86), which emerge from the intertwinement between art-making, research, teaching, and everyday life (Triggs & Irwin, 2019). This resonates well with how my everyday affective (Massumi, 2002) relation with the children in the classroom contributed to forming my doubts about exposing them. Drawing on Indigenous research ethics, Kara (2020) calls attention to “relational accountability” (p. 25) as an ethical responsibility. As a researcher, I am accountable for the relations that I engage with through my research. Here, I would like to pause to acknowledge the (in-direct) relation between many of the Eurocentric post-humanist and agential realist theories and Indigenous research theory and methodology (Deloria, 1999; Rosiek et al., 2020).

Understanding ethics as embodied and relational draws attention to the “complexities of the ethical encounter” (La Jevic & Springgay, 2008, pp. 68–69), which coincides with the choreographic-pedagogic and methodological implications the ethical itch has had on my research journey.

After my reading of the existing research field, I find there is a need for problematizing ethical aspects of research presentation and representation of research participants within the field of arts education and especially dance. In addition, what I miss from my readings is more research on how lived and embodied ethical dilemmas perform the pedagogical and choreographic content in dance education and research projects within this field, as well as works discussing how we can explore these issues through an embodied, choreographic, and dancing approach to the method of inquiry.

Theoretical concepts that I think with

I support my inquiry with theoretical notions and concepts that allow me to be close to the relational, lived, and embodied complexity of the ethical itch. In the introduction, I have weaved in the theoretical framework of agential realism that supports my inquiry. In the following, I give insight into the expanded notion of choreography (Foster, 2010; Klien & Valk, 2007) and the concepts of diffraction (Barad, 2007, 2014) and response-ability (Barad, 2007; Bozalek & Zembylas, 2017b; Despret, 2004).

Choreography as relational

The following quote from Klien and Valk (2007) shapes my understanding of choreography: “If the world is approached as a reality constructed of interactions, relationships, constellations and proportionalities, then choreography is seen as the aesthetic practice of setting those relations or setting the conditions for these relations to emerge” (p. 220). Choreography is in this sense no longer about composing dances or organizing movement (Foster, 2010), but is rather an apparatus of possibilities, creating movement (or stillness) of any kind (Foster, 2011). For example, I choreographed the dance workshops, with the aim of creating different possibilities for the pupils to create their own bird dances rather than copying mine. Choreography for Manning (2013) is less about planning ahead, but it rather “cleaves an occasion, activating its relational potential” (p. 76). This meant that my focus in the dance workshops was actively seeking to create connections between my dance, the children’s dances, the theme of birds, the pedagogical and artistic intentions set by myself and the teachers, the curriculum framework, and the classroom, instead of aiming towards a fixed end, like a performance. This shift in choreography allows me to engage with choreography as a relational practice.

The relational that Manning (2013) calls attention to is also further developed by Taylor and Fullagar (2022). To them, the relational aspect of choreography ties in with ethics and politics through “attending to the mattering of human-nonhuman choreographies” (2022, p. 43). Here, I would like to add that the ethical itch is such a choreography, emerging from how I attend to the mattering between the aesthetic force of the videos, the children as research participants, and my doubts about exposing them. Joy (2014) adds: “the choreographic also acts as a mode of provocation” (p. 27). As such, I understand the ethical itch as a provocation with choreographic qualities (Østern, 2018a).

The approach to choreography that I describe here is interwoven with ethics. Heathfield (2007) writes that “choreography is a transaction of flesh, an opening of one body to others, a vibration of limits” (unpaginated). With this, Heathfield entangles choreography with the embodied aspects of ethics that I have described earlier. As a choreographer-researcher-teacher, the questions of how I choreograph, or why, with, and what I choreograph (Østern, 2018a) then become important to me, as ethical-pedagogical-choreographic questions that vibrate with me and the ethical itch as I choreograph this inquiry.

Layering with diffraction

The research and this article are carried out as a diffractive inquiry (Barad, 2007, 2014; Bozalek & Zembylas, 2017a; Lenz Taguchi, 2012). Diffraction is a physical phenomenon describing the overlapping, bending, and spreading movement of waves meeting an obstacle (Barad, 2007). The core idea is that the intra-action between the obstacle and the wave creates new waves, “where the original wave partly remains within the new after its transformation” (Lenz Taguchi, 2012, p. 271). To me, this is close to the way I perceive the movement between the different layers of the research.

Response-ability in research, choreography, and dance education

A theoretical concept that helps me question how the lived, embodied, ethical, choreographic, pedagogic diffractions or entanglements of this inquiry perform each other is response-ability (Barad, 2007; Despret, 2004). Response-ability refers to the ability to respond (Barad, 2007; Despret, 2004), and making oneself available for response-ability to different matter (Juelskjær, 2019). According to Despret (2004), both human and nonhuman matter have the ability to respond to each other if they let each other do so.

My response-ability is connected to affecting and becoming affected, and to attuning myself and being available for such a process. The intensities and affects (Massumi, 2002) sensed through the skin, the heartbeat, the bloodstream, and the muscles thus perform my response-ability; they inform or perform how I act. Braidotti (2013) relates bodily intensities and ethics: “We are becoming posthuman ethical subjects in our multiple capacities for relations of all sorts and modes of communication by codes that transcend the linguistic sign by exceeding it in many directions” (p. 190). Braidotti’s words encourage me to continue working with bodily practices in my inquiry. Continuing along these lines, Chappell (2018) talks about “embodied dialogue” (p. 282) between both human and nonhuman bodies and its potential for creating new relations. What I read from these researchers is that attunement to the body and the senses makes grounds for the emergence of response-ability between human and nonhuman matter. My bodily attunement to the ethical itch renders me response-able to it.

When Despret (2004) talks about affecting and being affected as response-ability, she also brings in the notion of trust: an “emotional trust” (p. 122) that is performed through gestures and the bodies performing the gestures. Trust also connects with the notion of care. Haraway (2008) links care with curiosity, or rather the obligation to curiosity. In light of Despret (2004) and Haraway (2008), I propose that the ethical itch emerges from my ability to respond to the trust I sensed in the relationship between myself and the children in the dance workshops, with curious care.

Bozalek and Zembylas (2017b) propose a response-able pedagogy answering to “the attunement between what is done and how it is done” (p. 67). I would claim that also choreography and research, practiced as a relational approach as described in this article, are response-able practices.

The apparatus of inquiry

Cutting-together-apart an inquiry

I am cutting-together-apart (Barad, 2007) the ethical doubts, with the relational framework of the agential realist approach, with my practice as a choreographer-researcher-teacher, with the analytical questions, with the gaps in existing research. I am performing agential cuts (Barad, 2007), which are “a temporary separation between entanglements” (Bozalek & Fullagar, 2022, p. 30). I make an agential cut into the ethical itch, and I inquire into what relationships emerge within the cut. Making agential cuts is also of ethical matter, as the cuts I make perform the entanglements I am cutting into (Barad, 2007). Through a cut, I am creating certain entanglements and excluding others.

Even though the notion of cutting evokes the image of separating, agential cuts are performed through cutting-together-apart (Barad, 2007). As Juelskjær (2019) writes, “cutting and relating” (p. 79, my translation) happens when I am cutting-together-apart my own doubts and desires, creating a disturbance that this article is built around.

The method of inquiry is choreographed through the diffraction of the different practices, renderings (Irwin & Springgay, 2008; Le Blanc & Irwin, 2019), concepts, and experiences as they cut-together-apart. According to St. Pierre (2021), post-qualitative inquiry “never exists, it never is. It must be invented, created differently each time” (p. 6), and Kara (2020) points out that “ethical decision making […] allows for creativity” (p. 61). For example, engaging in a dancing practice as a part of the research process was a way of creating an apparatus of inquiry where I could deal with the ethical challenges I was facing (Østern, 2017). As an important disturbance or interruption, the ethical itch directs the inquiry into unanticipated directions (Irwin et al., 2006), in need of a “methodology of situations” (p.75). Choreographing the apparatus of inquiry I then understand as bringing different bodies, theories, and practices into movement (Klien, 2008), focusing on how they perform each other, and what is created through the relations that emerge through the situations and rendering practices that I set up.

Transcorporeal rendering practices

Doing research is, for me, a fieldwork of the body, a transcorporeal (Lenz Taguchi, 2012) process that is performative for the research. For example, the theoretical concepts that I think with (Jackson & Mazzei, 2012) in this inquiry are put in motion through dance, through writing, through walking, remembering, and sensing, which are material-discursive practices (Barad, 2007) of the body, or “rendering practices” (Myers, 2012). I am creating renderings from the research process that again could diffract into new meanings and insights. Irwin and Springgay (2008, see also Le Blanc & Irwin, 2019) write that renderings in a/r/tography are “flexible, intersubjective locations through which close analysis renders new understandings and meanings” (2008, p. xxviii). However, Le Blanc and Irwin (2019) stress that renderings are “meant to disturb, to displace and to raise questions” (p. 3). This happened to me, for example, when I started to create the video article. The videos, as itching renderings, performed my research and changed my initial direction (Le Blanc & Irwin, 2019).

Doing research with the body supports my relational approach to choreography and inquiry but is also rooted in the dance practice that I engage in, both in the dance project and as a tool for analysis in the inquiry. My dance practice builds on the post-modern wave where improvisation was an approach to both creating dances and performing dances (e.g., Foster, 2011; Fraleigh, 1987). The dance is entangled with the lived body (Fraleigh, 1987) of the dancer, emerging through a bodily listening to the human and non-human matter that I dance with. The way I dance is very much attuned with the way I do research.

Le Blanc and Irwin (2019) write that “art practice creates the conditions necessary for exchanges between materials, knowledge, objects and bodies to occur. Thus, the artist is engaged in a dynamic process of becoming, an exchange that sets things in motion” (p. 4). I would argue that this is what happens when I engage with the research through a transcorporeal apparatus, and through dancing and choreography as affective and artistic material-discursive practices.

Cutting-together-apart three stop-moments

In the following, the three stop-moments (Fels, 2015): Shared vulnerability and trust, Connection/disconnection, and Tuning into the ethical itch will together present a threshold into the final discussion.

Stop-moment one: Shared vulnerability and trust

As I went through the video material when preparing the video article, I experienced a diffraction (Barad, 2007, 2014) happening. I was drawn back into the workshops, and re-connected with the dances of the children as intensities and affects started to swirl around in my body. First and foremost, it was the tingling feeling spreading through the body when witnessing the pupils sharing their solo dances with each other. I enjoy how some of the children seem to be immersed in the dance: for example, Markus, who blew me away embodying a hunting bird, throwing himself to the floor in a swift movement. But a feeling of care also sneaks in, as I experience how some of the pupils are flickering their eyes or not remembering their movements.

The trust that the children had shown me in accepting my invitations to dance in the dance project suddenly struck me. A relation of emotional trust (Despret, 2004) had developed between us: The trust needed for exploring, concentrating, focusing, trying out, and sharing our dances (Figure 3). I had felt trusted to care, guide, and handle whatever hesitations or difficult feelings that emerged within the children dancing in the dance project. To display these moments of trust, in an open and accessible video article on the internet, disconnected in time and space from that special moment in the classroom, started to itch.

Stop-moment two: Connection/disconnection

I live near the school, and my everyday walk back home from my office (Figure 4) I often pass the children from the dance project. Some of them still recognize me; others do not. Sometimes they stop to chat, and sometimes we just go past each other on different sides of the street with a nod or a hi, or just in silence. I see them sometimes walking alone to soccer practice, or together with their families. These daily encounters performed affectively (Massumi, 2002) my relation with the children: nurtured my care for them and nurtured the doubts that I had about exposing them in the video article. The daily encounters reminded me that we are both connected and disconnected. From sharing, trusting, daring together in the videos, to crossing each other on the pavement, sometimes almost as strangers.

Even though I was still actively working with the dance project through my research, the children did not share the same journey. Since they were no longer consciously and actively involved in the research project, it felt problematic to expose them through the videos. It felt problematic giving others, strangers, insight into the intimate and vulnerable situations of the dance project. At the same time, I felt proud about what we had done in the dance project. With that feeling, I also felt an obligation to the field of dance education to share the project. I found myself being entangled with the children through the research, but also through everyday life itself (Triggs & Irwin, 2019), and I felt the obligation of our entanglement emerging as the ethical itch.

Stop-moment three: Tuning into the ethical itch

There was a diffraction happening between my desire to front the aesthetic force of the videos from the dance project in a video article, the doubts emerging from the feeling of connection/disconnection with the children, and the atmosphere of trust that had been established in the dance workshops. I was searching for a response-able practice (Bozalek & Zembylas, 2017b) to work myself through this ethical itch. If I was not to expose the children through the videos, how could I still highlight their dances that had made such an impact on me and my research? The idea of relating with the children through their own dances, and also through my own dance started to form. Maybe the dances, as affective renderings (Irwin & Springgay, 2008; Myers, 2012) or as bodily writings (Buono & Gonzalez, 2017), could help me question the ethical itch and diffract into sense-making (Le Blanc & Irwin, 2019)?

But how could I embark on such a practice? To me, it was important to cut-together-apart myself with the children’s movement, and not reflect them (Østern et al., 2021). I chose to learn the children’s dances, using both my bodily memory and the video footage to remember. After learning the children’s movements, I then allowed myself to play with them, to make them mine. Important to note is that I, in these dances, did not become the children (Buono & Gonzalez, 2017) but inquired into their dances through my own body. With my body as a transcorporeal apparatus (Barad, 2007; Lenz Taguchi, 2012), I made agential cuts into the children’s dances.

Discussion of emerging insights

As a starting point of this inquiry, I asked: What choreographic-pedagogical insights are created through diffracting with an ethical itch emerging from a dance project in elementary school? How can diffractive inquiry perform sense-making in research, choreography, and education? In the following, I expand from these questions, diffracting with the stop-moments and the theoretical framework.

Accompanying the children through dancing their dances

What could these danced and diffracted cutting-together-aparts create for my research process? The first dances I chose to learn were dances danced by pupils who seemed to enjoy dancing. These dances had developed a decided movement material and a clear execution of the dynamics of the movements.

After working with these dances for a while, a cascade of ethical questions emerged (Juelskjær, 2019): What about the dances that were not that developed and decided? Or dances danced by pupils who were insecure, or clearly showed signs of doubting themselves dancing? Was it right to also dance these dances? Perhaps, even, was it not actually more important to also dance these dances? But how would I do so without stepping into imitation of insecurity and vulnerability? These questions and disturbances (Le Blanc & Irwin, 2019) guided me towards a way of becoming-with different dances which, I felt, respected yet cultivated the palette of movements and dynamic qualities that the children’s dances offered me. The entanglement between aesthetics, education, and ethics is a choreographic-pedagogic insight that I bring with me. For the purpose of this article, I have edited one raw-cut video1 rendering from a studio session where I worked with the dance of pupil Ethan (Figure 5).

By engaging in the children’s movements through my own body, I felt that my dances were a way of accompanying the children into the world without exposing them, but at the same time giving attention to their research contribution through sharing their dance aesthetics. This is also something that is transferable to in-class activities in dance education and challenges more traditional hierarchies of the children dancing the teachers dances. However, I could not stop myself from wondering if, in this way, I was actually silencing their voices (Pickering & Kara, 2017), rather than letting the videos represent the children’s dances as they were. This is another ethical perspective that arises from this inquiry, which could be continued through a project where the children are actively participating in the ethical discussion. An approach in such a project could be inquiring into how dancing each other’s dances would add to rendering our voices response-able to each other. To me, this is a beautiful example of the necessary disturbances that dance can provoke in a research process (Le Blanc & Irwin, 2019).

Dance aesthetics becoming-with response-ability

The whole palette of the children’s different movement material was available to me, because they had all been shared and performed in the classroom during the dance project. This tells me that in our dance project also insecure or fumbling dances were given space to be performed. This makes me think back to relational accountability (Kara, 2020), and what I see as an ethical choreographic-pedagogic obligation in dance education: Creating invitations that allow for response-ability for every single child. Making visible the fumbling dances was giving them value and gave the teachers and myself the possibility to respond with curious care (Haraway, 2008).

The choreographic-pedagogic insights that I have described above are an attempt to show how the diffractive inquiry of the ethical itch also provoked or invited me to think with the pedagogical and choreographic content of the dance project. This is a methodological contribution that explores the potential that diffractive inquiry has to cut into the complexities of dance education research – but not only that. Cutting-together-apart with the concept of response-able pedagogy (Bozalek & Zembylas, 2017b), I propose to see attunement to the relational and embodied method of inquiry that I have described here as a response-able research practice: A research practice that takes into account and explores through an artistic, lived, and affective perspective the ethico-onto-epistemological (Barad, 2007) implications that are set in motion through research. In the following, I will discuss how my diffractive and response-able research practice allows me to create entanglements between the ethical, aesthetic, and pedagogic content of the dance project.

Renderings provoking new questions

The fact that Elisabeth was moving with the dance has performed how I have been able to engage aesthetically with the dance workshops in the aftermath of the Bird project. Not only have I become more self-aware of my own choreographic-researching-teaching practice, but the videos somehow provoke the ethical in themselves, through the intimacy that I sense in the aesthetic expression of the videos. They are renderings (Irwin & Springgay, 2008; Le Blanc & Irwin, 2019) of how Elisabeth related to the children, to the dance, to the project. This makes me wonder about the importance of how Elisabeth’s way of recording, and how the videos, as non-human matter, have performed the insights and questions that has emerged in this inquiry.

Cutting-together-apart with an “ethics of engagement” (Pickering & Kara, 2017, p. 50) working with the children’s dances evokes new ethical provocations that is of choreographic-pedagogical interest: How do I do justice (Barad, 2007) to the children’s dances, both in the classroom and when I dance them? Or how do I manoeuvre between, for example, imitation, appropriation, diffraction, or reflection as I dance the children’s dances? How does the children’s dance aesthetics perform my dance aesthetics when I am a visiting the school? Through these choreographic-pedagogic provocations created through the diffractive inquiry, I see entanglements between the in-class activities that I propose and the research practice in dance education. This is a good example of how dance can perform as an a/r/tographic practice creating movement of all sorts (Le Blanc & Irwin, 2019). Also, with these questions I want to stress the need for careful attention to be paid to how we create these kinds of ethical-aesthetic-pedagogic spaces in both research, art, and education.

Creating response-able research practices

In this inquiry, I have problematized how ethical issues perform and entangle with the methodological, choreographic, and pedagogic layers in a dance education research project. Cutting-together-apart stop-moments through a transcorporeal apparatus where dancing took an important role, and building on Bozalek and Zembylas (2017b) response-able pedagogies, I propose a response-able research practice: a relational approach, or attunement to research-pedagogy-choreography-ethics. Through a bodily and artistic approach to research methodology, I am building on a/r/tographic research (Irwin & Springgay, 2008; La Jevic & Springgay, 2008; Le Blanc & Irwin, 2019) and expanding further within dance education, choreography, and a performative and agential realist approach. This is my contribution to the ongoing movement of a/r/tography.

I see potential to build on the insights from this project, spinning from the ethical issues that has emerged through writing this article, but also to explore further the notion of response-ability. For example, a possible continuation could be a future dance education research project where the children are involved in choreographing the video renderings, engaging in the ethical discussions that emerge. Such a project has the potential to actively deal with the ethical relationships (La Jevic & Springgay, 2008) as shared between children and grown-ups. It would challenge power hierarchies, and the narrative privilege (Ellingson, 2017), related to dance aesthetics, but also to education and research.

I understand choreography and dance as relational and ethical practices, both in education, arts, and research. What and how we dance and choreograph then becomes an important pedagogical, ethical, artistic, and research question, which will continue to linger with me as I move on with my choreographing-researching-teaching practice.

References

- Anttila, E., Martin, R., & Svendler Nielsen, C. (2019). Performing differences in/through dance: The significance of dialogical, or third spaces in creating conditions for learning and living together. Thinking Skills and Creativity, 31, 209–216. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tsc.2018.12.006

- Anttila, E., & Sansom, A. N. (2012). Movement, embodiement and creativity. In O. Saracho (Ed.), Contemporary perspectives in early childhood education (pp. 179–204). Information Age Publishers.

- Austin, J. L. (1975). Conditions for happy performatives. In J. O. Urmson, & M. Sbisà (Eds.), How to do things with words. The William James lectures delivered at Harvard University in 1955 (2nd ed., pp. 12–24). Oxford University Press.

- Barad, K. (2007). Meeting the universe halfway: Quantum physics and the entanglement of matter and meaning. Duke University Press.

- Barad, K. (2012). On touching – the inhuman that therefore I am. Differences: A Journal of Feminist Cultural Studies, 23(3), 206–223. https://doi.org/10.1215/10407391-1892943

- Barad, K. (2014). Diffracting diffraction: Cutting together-apart. Parallax, 20(3), 168–187. https://doi.org/10.1080/13534645.2014.927623

- Bickel, B., Springgay, S., Beer, R., Irwin, R. L., Grauer, K., & Xiong, G. (2011). A/r/tographic collaboration as radical relatedness. International Journal of Qualitative Methods, 10(1), 86–102. https://doi.org/10.1177/160940691101000

- Bozalek, V., & Fullagar, S. (2022). Agential cut. In K. Murris (Ed.), A glossary for doing postqualitative, new materialist and critical posthumanist research across disciplines (pp. 30–31). Routledge.

- Bozalek, V., & Zembylas, M. (2017a). Diffraction or reflection? Sketching the contours of two methodologies in educational research. International Journal of Qualitative Studies in Education, 30(2), 111–127. https://doi.org/10.1080/09518398.2016.1201166

- Bozalek, V., & Zembylas, M. (2017b). Towards a response-able pedagogy across higher education institutions in post-apartheid South Africa: An ethico-political analysis. Education as Change, 21(2), 62–85. https://doi.org/10.17159/1947-9417/2017/2017

- Braidotti, R. (2013). The posthuman. Polity Press.

- Buono, A., & Gonzalez, C. H. (2017). Bodily writing and performative inquiry: Inviting an arts-based research methodology into collaborative doctoral research vocabularies. International Journal of Education & the Arts, 18(36), 1–20. http://www.ijea.org/v18n36/

- Chappell, K. (2018). From wise humanising creativity to (post-humanising) creativity. In K. Snepvangers, P. Thomson, & A. Harris (Eds.), Creativity policy, partnerships and practice in education (pp. 270–306). Palgrave MacMillan.

- Chappell, K. (2022). Researching posthumanizing creativity: Expanding, shifting, and disrupting. Qualitative Inquiry, 28(5), 496–506. https://doi.org/10.1177/10778004211065802

- Deloria, V. (1999). Spirit and reason: The Vine Deloria, Jr. reader. Fulcrum Publishing.

- Despret, V. (2004). The body we care for: Figures of anthropo-zoo-genesis. Body & Society, 10(2–3), 111–134. https://doi.org/10.1177/1357034X04042938

- Ellingson, L. L. (2017). Embodiment in qualitative research. Routledge.

- Fels, L. (2010). Coming into presence: The unfolding of a moment. Journal of Educational Controversy, 5(1), 1–15. http://cedar.wwu.edu/jec/vol5/iss1/8

- Fels, L. (2015). Performative inquiry: Releasing regret. In S. Schonmann (Ed.), International yearbook for research in arts education. The wisdom of the many – Key issues in arts education (Vol. 3, pp. 510–514). Waxmann.

- Flønes, M., Andersen, T., Helgeland Nymark, M., Brinchmann, M., & Åreskjold Sande, K. (2022). Plunged into dance. Creating choreographic-pedagogic propositions as a collaborative learning community in primary school. Reconceptualizing Educational Research Methodology, 13(2), 74–98. https://doi.org/10.7577/rerm.4777

- Foster, S. L. (2010). Choreographing your move. In S. Rosenthal (Ed.), Move. Choreographing you. Art and dance since the 1960s (pp. 32–37). Hayward Publishing.

- Foster, S. L. (2011). Choreographing empathy. Kinesthesia in performance. Routledge.

- Fraleigh, S. H. (1987). Dance and the lived body. A descriptive aesthetics. University of Pittsburg Press.

- Gilbert, A. G. (2015). Creative dance for all ages. A conceptual approach (2nd ed.). Human Kinetics.

- Haraway, D. J. (2008). When species meet. University of Minnesota Press.

- Haseman, B. (2006). A manifesto for performative research. Media International Australia, 118(1), 98–106. https://doi.org/10.1177/1329878X0611800113

- Heathfield, A. (2007). What is choreography. Corpus. https://www.corpusweb.net/answers-2228.html

- Irwin, R. L. (2004). A/r/tography: A metonymic métissage In R. L. Irwin, & A. de Cosson (Eds.), A/r/tography: Rendering self through arts-based living inquiry (pp. 27–37). Pacific Educational Press.

- Irwin, R. L., Beer, R., Springgay, S., Grauer, K., Xiong, G., & Bickel, B. (2006). The rhizomatic relations of a/r/tography. Studies in Art Education, 48(1), 70–88. https://doi.org/10.1080/00393541.2006.11650500

- Irwin, R. L., & Springgay, S. (2008). A/r/tography as practice-based research. In S. Springgay, R. L. Irwin, C. Leggo, & P. Gouzouasis (Eds.), Being with a/r/tography (pp. xix–xxxiii). Sense.

- Jackson, A. Y., & Mazzei, L. (2012). Thinking with theory in qualitative research: Viewing data across multiple perspectives. Routledge.

- Josselson, R. (2007). The ethical attitude in narrative research: Principles and practicalities. In D. J. Clandinin (Ed.), Handbook of narrative inquiry. Mapping a methodology (pp. 537–566). Sage Publications.

- Joy, J. (2014). The choreographic. MIT Press.

- Juelskjær, M. (2019). At tænke med agential realisme [Thinking with agential realism]. Nyt fra Samfundsvidenskaberne.

- Kara, H. (2020). Creative research methods. A practical guide (2nd ed.). Policy Press.

- Klien, M., & Valk, S. (2007). What do you choreograph at the end of the world? In R. Ojala, & K. Takala (Eds.), Zodiak: Uuden tanssin tähden (pp. 212–231). Like. https://www.michaelklien.com/resource/download/zodiak-article.pdf

- Klien, M. (2008). Choreography as an aesthetics of change. Edinburgh College of Art. https://www.michaelklien.com/resource/download/phd-klien-main-document.pdf

- Kuby, C. R., & Zhao, W. (2022). Ethico-onto-epistemology. In K. Murris (Ed.), A glossary for doing postqualitative, new materialist and critical posthumanist research across disciplines (pp. 64–65). Routledge.

- La Jevic, L., & Springgay, S. (2008). A/r/tography as an ethics of embodiement. Visual journals in preservice education. Qualitative Inquiry, 14(1), 67–89. https://doi.org/10.1177/1077800407304509

- Le Blanc, N., & Irwin, R. L. (2019). A/r/tography. Oxford Research Encyclopedia of Education.

- Lenz Taguchi, H. (2012). A diffractive and Deleuzian approach to analysing interview data. Feminist Theory, 13(3), 265–281. https://doi.org/10.1177/1464700112456001

- Liamputtong, P. (2006). Researching the vulnerable. A guide to sensitive research methods. Sage Publications.

- Manning, E. (2013). Always more than one. Individuation’s dance. Duke University Press.

- Massumi, B. (2002). Parables for the virtual: Movement, affect, sensation. Duke University Press.

- Myers, N. (2012). Dance your PhD: Embodied animations, body experiments and the affective entanglements of life science research. Body & Society, 18(1), 151–189. https://doi.org/10.1177/1357034X11430965

- NESH. (2016). Forskningsetiske retningslinjer for samfunnsvitenskap, humaniora, juss og teologi [Ethical guidelines for research in social science, humanities, law and theology]. De Nasjonale Forskningsetiske Komiteene.

- Østern, T. P. (2010). Teaching dance spaciously. Nordic Journal of Dance, 1, 47–57. http://www.nordicjournalofdance.com/TeachingDanceSpaciously.pdf

- Østern, T. P. (2017). Å forske med kunsten som metodologisk praksis med aesthesis som mandat [Doing research with the arts as a methodological practice with aesthetis as mandate]. Journal for Research in Arts and Sports Education, Special Issue: «Å forske med kunsten», 1, 7–27. https://doi.org/10.23865/jased.v1.982

- Østern, T. P. (2018a). Koreografi-didaktiske sammenfiltringer [Choreographic-pedagogic entanglements]. In S. Styve Holte, A. -C. Kongsness, & V. M. Sortland (Eds.), KOREOGRAFI 2018 (pp. 24–30). Kolofon.

- Østern, T. P. (2018b). Den skapende og undervisende dansekunstneren [The creative and teaching dance artist]. In E. Angelo, & S. Kalsnes (Eds.), Kunstner eller lærer? Profesjonsdilemmaer i musikk- og kunstpedagogisk utdanning (pp. 205–217). Cappelen Damm Akademisk.

- Østern, T. P., Jusslin, S., Knudsen, K. N., Maapalo, P., & Bjørkøy, I. (2021). A performative paradigm for post-qualitative inquiry. Qualitative Research. https://doi.org/10.1177/14687941211027444

- Pickering, L., & Kara, H. (2017). Presenting and representing others: Towards an ethics of engagement. International Journal of Social Research Methodology, 20(3), 299–309. https://doi.org/10.1080/13645579.2017.1287875

- Pullen, A., & Rhodes, C. (2015). Ethics, embodiment and organizations. Organization, 22(2), 159–165. https://doi.org/10.1177/1350508414558727

- Richards, S., Clarck, J., & Boggis, A. (2015). Ethical research with children. Untold narratives and taboos. Palgrave Macmillan.

- Risner, D., & Schupp, K. (Eds.). (2019). Ethical dilemmas in dance education: Case studies on humanizing dance pedagogy. McFarland.

- Rosenberg, T. E. (2013). Intermingled bodies. Distributed agency in an expanded appreciation of making. FormAkademisk, 6(2), 1–18. https://doi.org/10.7577/formakademisk.658

- Rosiek, J. L., Snyder, J., & Pratt, S. L. (2020). The new materialisms and indigenous theories of non-human agency: Making the case for respectful anti-colonial engagement. Qualitative Inquiry, 26(3–4), 331–346. https://doi.org/10.1177/1077800419830135

- Stinson, S. W. (2016). Seeking a feminist pedagogy for children’s dance (1988). In S. W. Stinson (Ed.), Embodied curriculum theory and research in arts education. A dance scholar’s search for meaning (pp. 31–52). Springer.

- St. Pierre, E. A. (2021). Post qualitative inquiry, the refusal of method, and the risk of the new. Qualitative Inquiry, 27(1), 3–9. https://doi.org/10.1177/1077800419863005

- Taylor, C. A., & Fullagar, S. (2022). Choreographies. In K. Murris (Ed.), A glossary for doing postqualitative, new materialist and critical posthumanist research across disciplines (pp. 42–43). Routledge.

- Triggs, V., & Irwin, R. L. (2019). Pedagogy and the a/r/tographic invitation. In R. Hickman, J. Baldacchino, K. Freedman, E. Hall, & N. Meager (Eds.), The international encyclopedia of art and design education. John Wiley & Sons. https://doi.org/10.1002/9781118978061.ead028

- von Hantelmann, D. (2014). The experiential turn. In E. Carpenter (Ed.), On performativity (Vol. 1). Walker Art Center. http://walkerart.org/collections/publications/performativity/experiential-turn