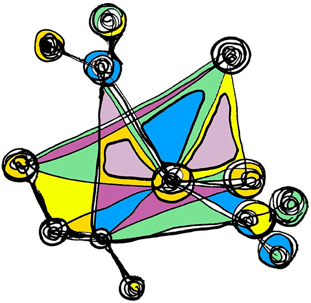

Figure 1. Visual documentation: Bucket and plastic animals; situated teacher idea turned to act. To get the children hooked (same session as mentioned in Scheme 1).

Peer-reviewed article

Hannah Kaihovirta*,

Åbo Akademi University, Faculty of Education and Welfare Studies, Vaasa, Finland

Abstract

The aim for this article is, based on theory, and through practice, to generate awareness on an activity that many teachers perform; the practice of improvisation. Improvisation is a professional method in teaching practice that very often is so taken-for-granted that it is to some extent under-theorized in the area of educational research. In education, an important purpose of the robustness of research involves educational practice. Therefore, the article is informed by a deductive discourse, where theory leads practice. The practice investigated is based on arts-based co-teaching project experiences made in a primary school in Vaasa, Finland in the school year 2015–2016. One theory that interested me as a form of artist-researcher-teacher intervention in the project was teacher improvisation. In the article improvisation is approached from a position formed by a combination of improvisation mindsets and participatory research practice. My researcher identity and the research method are informed by a/r/tography. This means that the inquiry is interpreted as an evolving process where the article production is part of the process. As a result, I create representations that I suggest to function as three mindsets about improvisation in teaching: the mosaic, the kaleidoscope and the rhizome.

Keywords: Improvisation in teaching; a/r/t-ography; co-teaching; art based teachinh; mindset

Sammandrag

Avsikten med denna artikel är att, baserat på teori, och genom praktik, skapa medvetenhet om en aktivitet som manga lärare utövar: att praktisera improvisation. Improvisation är en professionell metod i undervisningspraktik som mycket ofta tas för given, och som i någon mån är underteoretiserad inom fältet pedagogisk forskning. I utbildningsforskning bidrar praktisk undervisning till att styrka hållbarheten hos forskningen. Därför bygger den här artikeln på en deduktiv diskurs, där teori leder praktik. Praktiken som studeras är baserad på konstbaserade kollaborativa undervisningserfarenheter. En klasslärare tog initiativ till en teoribaserad undervisningspraktik i en lågstadieskoa i Vasa, Finland, skolåret 2015–2016. En teori som intresserade mig som en sorts konstnär-forskare-lärare-intervention i projektet var lärarimprovisation. I artikeln studeras improvisation utgående från en position formad genom en kombination av tänkesätt i improvisation och deltagande forskningspraktik. Min forskaridentitet är byggd på a/r/t-ografi. Det betyder att undersökningen är tolkad som en process som utvecklas där det att producera artikeln är en del av processen. Som resultat skapar jag tre representationer, som jag föreslår kan fungera som tre (nya) sätt att tänka om improvisation i undervisning: mosaik, kalejdoskop och rhizom.

Sökord: Improvisation i undervisning; a/r/t-ografi; lärarsamarbete; konstbaserad undervisning; sätt att tänka

Received: August 2016; Accepted: November 2016; Published: January 2017

*Correspondence: Hannah Kaihovirta, Åbo Akademi University, Rantakatu 2 Vaasa, Finland. Email: Hannah.Kaihovirta@abo.fi

©2017 Hannah Kaihovirta. This is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), allowing third parties to copy and redistribute the material in any medium or format and to remix, transform, and build upon the material for any purpose, even commercially, provided the original work is properly cited and states its license.

Citation: Hannah Kaihovirta. “Teacher Improvisation as Processes of Mosaic, Kaleidoscope and Rhizome – an arts-based, co-teaching approach.” Journal for Research in Arts and Sports Education, Vol. 1, 2017, pp. 1–15. http://dx.doi.org/10.23865/jased.v1.508

The research question guiding the article is: What are the elements that can be recognised as teacher improvisation in the project experiences and what implications do they have on the approach to teacher practice? In the studied project the following questions related to improvisation and the development of teachers’ professional work were articulated: What are the elements of meaning and interest in teacher improvisation practice? How can we better understand the character of improvisation in teaching practice? How do the connections between art and pedagogy practice show when approaching teacher improvisation? These research questions guide the inquiry process presented in this article.

Understanding a phenomenon that has been unarticulated in experienced teaching practice is, of course, something that is recognised as a process of professional reflection, development and learning. Nevertheless, understanding also is a form of epistemology (as interpretation) for the teaching practice itself. The teaching practice I have been involved in has been framed by the notion of art experience as learning and processes of education through art. My deductive approach to teaching practice and reasoning generates an epistemology in the practice that the understanding is based on an approach to teaching and learning where knowledge is considered not as absolute, universal and individual, but as a process with hermeneutic character, acknowledging that understanding something (in this case the theory studied on improvisation) is a model for communication (cf. Ricoeur, 2006). In parallel, understanding is as well regarded as ontology (for the researcher), where meaning is constructed in conversations between people.

My interest in teacher improvisation materializes in experiences in teaching through art. In this article I elaborate teacher improvisation through the lenses of defining the aesthetic character1 of such teacher actions that I observe as improvisation. This is a strong research positioning. For me, with an artistic background, this positioning comes to view as an important scholarly act. Positioning involves here negotiation and becoming over and over again as an artist, researcher and teacher. I am in the position informed by Nelson Goodman’s (1968) theories on literacy as world making, and especially here in arts literacy as world making, particularly in the notions of direction and domain in teaching. The notion of positioning is also a source for transformation. For example, in teaching positioning is not only a question of power but also about risking. To teach is a question of taking risks. To teach is to be human, to teach means to accept the fundamental weakness of the purposeful, creative process we call education (cf. Biesta, 2013).2 This I find fascinating in relation to the theories studied on improvisation. With artist experience I claim that improvisation is a way of taking a risk; instead of turning thoughts into representations by will, one must improvise and let the will rest. Improvisation becomes a trust in understanding embodied knowledge of artistic expression.

The experience of co-teaching has an impact on the theme of the article for a reason. The collaboration between the teacher (in the project described and interpreted) and myself has a long professional history. The teacher and I went through several stages of developing arts-based teaching in basic education starting with a supportive and complementary co-teaching practice (between 1997–2000) in a project defined as Teacher and participating artist in school, transformed into parallel co- teaching in 2000–2004 through a project based on the idea of Teacher and artist in residency in school. Since 2004 the co-teaching has been articulated as teaching artistry with support from the methods and methodology of A/r/tography (cf. Irwin, De Cosson, & Pinar, 2004; Springgay, Irwin, Leggo, & Gouzouasis, 2008) and ideas on relational aesthetics (cf. Bourriaud, 2004) and participatory art (cf. Bishop, 2006). Through the years a strong reliance and confidence in collaboration, with each other, with arts-based teaching, and children’s attitude to learning has motivated us to create more challenging learning concepts and push teaching structures beyond the expected.

The recognition of improvisation as offering potential for teaching and learning in school is one of the new areas I have been eager to explore and articulate. In the book What Makes Good Teachers Great. Artful Balance of Structure and Improvisation (2011) Keith Sawyer describes how early studies in the 1970’s show how teachers’ expertise in the classroom is built upon structures that teachers created themselves, as ways to enhance teaching, manage classrooms, and handle problems that may arise. In parallel the teacher practice is scaffolded by teacher education, structures that guide teaching by law, administration, the curriculum or other state and federal guidelines. Sawyer’s study also showed that new teachers tend to follow models and curricula literally to a greater degree than experienced teachers. The study revealed that experienced teachers have a greater repertoire of models at their disposal and they practice improvisation and creativity in their teaching a different way to their less experienced colleagues (Sawyer, 2011). Sawyer points out that in education the profession largely involves working within given structures, being creative within them, and creating a favorable learning environment where all pupils have the opportunity to optimize their learning and get to acquire knowledge and skills. He claims that the teacher’s ability to improvise is an important facet of knowledge needed for the operational culture in school. He states that improvisation as a form as well as a method needs to get more attention when it comes to the development of teacher practice, teacher education and teacher training.

My interest in Sawyer’s argument concerning the relation between improvisation and educational actions can be anchored in research conducted in the new millennium. In the publication Creating Conversations: Improvisation in Everyday Discourse (2011) Sawyer defines teacher improvisation by arguing that teaching is conversation and that every good conversation includes improvisation. He does not pinpoint the artistic dimension3 of teaching, nonetheless does he deny artistry in teaching. Sawyer parallels improvisation with creativity done in a conversation process (Cf. Sawyer, 2011). Sawyer claims that in conversations, especially in informal ones, people improvise. He insists that improvisation is about communication and suggests that improvisation is expressed best in human cooperation. So far I have referred to Sawyer’s description of improvisation in teaching. Informed by the notion that conversation and human cooperation is guided by improvisation I started to rethink the arts-based teaching acts within the co-teaching practice in the project mentioned. I observed elements in the teaching experiences that could be defined by concepts articulated as improvisation. I was enlightened by the mirroring effect in Stacy Dezutter’s article Professional Improvisation and Teacher Education (2011) where she recognizes that improvisation rarely has been an explicit part in the discourse of teaching. She notices that improvisation not articulated in teacher education limits the portability as a profession to advance knowledge and capacity for the improvising practice well. (cf. Dezutter, 2011)

This notion made my approach to the research process clearer. Here I find it correspondingly noteworthy to connect to the publication Conversations on Finnish Art Education (2015) published to celebrate the centennial of Finnish art education. In the introduction to the book, Kallio-Tavin and Pullinen reflect upon the observation that contemporary Finnish art educational practices are seen networking with the practices of other cultures. This networking is in the title of the book transformed to conversations, which I find an inspiring meta-level to be aware of when approaching the “conversations” in the arts-based project explored in this article generated.

The teacher educators Toivanen, Komulainen, and Ruismäki, in a study published in 2011, argue that one of the most difficult skills for teacher students to acquire is how to be confident in moving away from structured routines and lead disciplined improvisation in teaching practice. They claim that teacher students need the routines for creating a professional base. The students need to learn how to flexibly apply and rethink routines in future teaching practice and be confident in that teaching is based on rich interaction and creative passion. According to Toivanen, Komulainen and Ruismäki this wide range of competences can be taught through drama and improvisational exercises. They believe that drama and improvisation can improve the quality of learning and the quality of life in teacher education because drama in education can be used to extend the worldview and fictionally deal with various situations in life. (Toivanen, Komulainen & Ruismäki, 2011)

Sawyer (2001) observes that improvisational performance is relevant to empirical study of all creative genres for two central reasons. First, the creative process that goes on in the mind of creator is generally inaccessible to the researcher, in parts because it occurs over long time periods. Second, many improvisational performance genres are fundamentally collaborative. Furthermore, he states that improvisational creativity is ephemeral and does not generate a permanent product, which Sawyer explains can be one reason why it has been easy to neglect as a central form of teaching, teaching strategies and methods. Having a long experience of working as teaching artist in education and educational settings I recognise that I do have a possibility to promote dialogues on improvisation as a professional skill since artists are very familiar with improvisation. Though it can be difficult to pinpoint in art as learning practice and aesthetic learning processes. Embodying this notion of artist experience as agency for teaching, for example Nettl explains an artist perspective on improvisation through the notion that improvisation is not expression of accident but rather expression on accumulated yearning on dreams and wisdom (Nettl, in Solis & Nettl, 2009).

Nettl further explains that in contemporary art contexts improvisation is now accepted as one of many facets in an artistic process. Improvisation is, according to Nettl, not an expression of accident. I claim that neither is teaching and learning. This is one element that creates a robust connection between teaching and improvisation and needs to be taken into consideration in education as well as in the discourse of research and teachers’ professional development. Nettl points out that it is time to understand improvisation in various forms and contexts of teaching.

Also Feisst (2009) reveals an important approach to the understanding of improvisation in teaching. In her inquiry into John Cage’s relation to improvisation she finds out that Cage conceptualizes four aspects that are central for music composing processes; material, structure, method and form. Feisst explains that three of the four components could be improvised, form, material and method, and that three could be organized, structure, method and material. And the two in the middle, material and method could be either organized or improvised. (cf. Feisst, 2009). Further Feisst reveals interesting perspectives on the particular misunderstanding on improvisation as a big illusion. Feisst comments on the misunderstanding of improvisation as a completely new invention of practice. More often it is about to try and create a new order of practice. Actually the improvisational idea of tabula rasa is quite impossible as improvisation always happens within a temporal space, refers to the memory of time, because it bases on memory and all the different experiences it can release (cf. Feisst, 2009). Feisst’s confidence in her arguments relies on an educational tradition where improvisation as a method for learning and performance in music has been taught and researched for years. Inquiry into the area of music exposes important knowledge about what improvisation is. For example, John Kratus (Kratus, 1996) has defined a seven-staged development process of teaching and learning music improvisation with children (Kratus, 1996).4 It is possible to elaborate with these into other areas of improvisation. His description of how experts are oriented to create improvisation in a working process whereas novices are involved in the process of improvising for its own sake is possible to resonate with teacher improvisation structures. Furthermore, Kratus (1996) describes the skill to improvise in a way that seems to be automatic and natural for an expert while a novice who has not developed skills will be hampered in producing a fluid improvisation. It is possible to assume the situation being the same in teacher improvisation.

The areas of theatre and drama offer models for approaching the concept of teacher improvisation. Actually drama education is the area where I myself experienced improvisation and became aware of the phenomena in my artistic and teaching acts. Johnstone’s (1985) exploration of Stanislavski’s impact on theatre improvisation when speaking in terms of the dynamics of a play, its action, the thoughts and feelings communicated, the (fictive) world in which certain characters live - all have had a great influence on how I have been aware of improvisation in teaching. And as a final point for this chapter of argumentation, I recognize that teaching is leadership in a thinking manner. To teach is to lead in a generous way were conversation5 is a device for learning. If we talk about improvisation as a central part of conversation, then Robert Denhart’s and Janet Denhart’s perception that great leadership (2008) includes improvisation has to be acknowledged when discussing teacher improvisation. Improvisation is in their description listening, a very sensitive ability to notice rhythm and timing as central aspects of communication.

There exists a body of research on embodied pedagogy (cf. Bresler, 2004) and on improvisation in teaching, but in my experience improvisation as a teaching strategy has been a neglected competence. In teachers’ everyday discussions, professional forums and in teacher education courses on pedagogy and teaching very rarely teachers mention improvisation as a skill. What strikes me within these discussions is that as an a/rt/ographer I become aware of the efforts artists transform acts of improvisation into articulation on their tacit mindsets, strategies and skills as professional knowledge. I realise that for me as an artist the act of improvisation seems to be a much more natural part of articulating professionalism than for me as a teacher. This insight is a subjective one, and can be explored through the a/r/tography methodology. Through this methodology, I as a researcher, can be informed by the idea of radical otherness (experienced as an artist-researcher working among teachers), and through that understand the possibilities of one professional field in the context of another. Traditionally visual artists do not necessarily as musicians and actors use the word improvisation to explain the improvisatory processes in their work.6 But then again, taking a look at the contemporary art scene where performance art and crossover productions have become familiar for artists in all genres the concept of improvisation emerges as a new area of practice, knowledge and inquiry to discover. So, converting back to the arena of education in the light of arts-based teaching; teaching becomes an emerging process, where understanding improvisation as meaningful teaching can open up areas of educational practice that include unpredictability, the not expected or not yet imagined.

A/r/tography as method and methodology is challenging and at the same time generative and productive in an educational research context. One topic that has caught my attention in a/r/tography research is the recent shift of focus in the discourse; from artist’s perspective to the pedagogical lens of the artist-researcher. This creates a new kind of research space where it is possible to interconnect scholarship on epistemology, ontology, philosophy, and methodology with contemporary art practice. For me this means that rhizomatic mindsets7 on artist knowledge, researcher knowledge, and teacher knowledge can be linked with experiences and documentation. This is the attempt made in the presented project. In a/r/tography the roles of artist, researcher and teacher are integrated and they create a third space, where understanding is generated through theory and experience that meets in a hybrid (cf. Irwin, De Cosson, Pinar, 2004). Informed by the promising literature and theorizing writings on a/r/tography (Irwin, De Cosson, & Pinar, 2004; Springgay, Irwin, Leggo, & Gouzouasis, 2008) the theories studied are transformed to patterns that figures, and configures, lived experience to representations, and formations on teacher improvisation. In the patterns the in-betweens8 function as a lingering space and together they result in three visual formations that offer an outcome of this study. The process will here become a product through the notion that a/r/tography is a method that to some extent un-design more formal formats of qualitative research (cf. Araujo, 2012). The experiences from project described in this article are linked to a longer perspective on my role as an artist-researcher-teacher. This generates a hermeneutic quality to the research, in which the reasoning is bending in several directions through the interpretation process.9 My a/r/tographer experience is that improvisatory teaching experiences are not always possible to articulate in words. Instead they are possible to articulate in art, acts or other modalities. They are understood within the context, the frames set for learning. Therefore I as a researcher find the deductive method appealing; having theory as a background in the practice makes it possible to be open for the embodied knowledge that I as an a/r/tographer experience in practice. My researcher approach strives to linger between poles of experience and reflection and steer my researcher acts to convert the experiences into scholarly mindsets that can be examined also by others.

In contemporary art the desire to move viewers out of the role of passive observers and into the role of producers is one of the hallmarks in the 21st century art scene. More recently, this kind of participatory art has gone so far as to encourage and produce new social relationships (cf. Bishop, 2006). This is a notion that I bring with me into classroom practice. The relation between an a/r/tographer, a teacher and students implies a new form of relations in education. As an a/r/tographer I in this study have turned my mind into being sensitive for improvisation as an artist, as a researcher and as a teacher.

The project that was examined for approaching teacher improvisation was informed by a storyline approach to teaching and learning.10 In the classroom practice the project was titled HOME SITE: From Bed & Breakfast Farm to Web Pages.11 The themes that the pupils worked on were local-global sustainability, farming, ecology, communication, computer skills and collaborative learning. The children were 3rd year primary school pupils. The whole process of the project was from a co-teaching perspective laid out as six sessions. One of the sessions is here represented as a scheme created from notes categorized in three approaches in teaching practice; spontaneous ideas, possibility to realise and improvisatory actions (scheme 1). The scheme is used to recall the experience of improvisation on site. The experience is analysed through the artist-researcher-teacher lens. The elements placed in the scheme create space for teacher improvisation if one dares to try it out. In the scheme presented here, three main approaches conducts the improvisatory teaching act:

The three approaches are characteristics chosen for describing the practice explored. The three approaches are actually interpreted here as triggers for teacher improvisation. It is important to understand that the approaches are in this given order due to the specific discourse and research question of this article: What are the elements that can be recognised as improvisation in the teaching experiences and what implications do that have on the approach to teacher practice? In another discourse it would be possible to place them differently. The order is also a reminder of the fact that school settings are structured in a certain pattern by curriculum, planning, group sizes, classroom sizes, classroom settings, and schedules and of course clear learning goals. It is important to notice that it is possible to change the order in a dynamic or rhizomatic pattern. In the scheme, the approaches are turned into titles on teaching acts.

One of the main ideas in the improvisatory work that we elaborated in the project was the idea of exploring the unexpected act in the situation. The scheme presented gives an idea of the juxtaposition experienced between given school structures and open learning structures created in the project. The juxtaposition is an acknowledgment of safe school structure; a possibility for all involved being secure for letting one free in the set of improvisation.

The understanding of playing with ideas, symbols and ideas on material (in this case farm animals in plastic) and open learning structures is one of the most challenging parts to explain as improvisation and transmitting to concepts of understanding teacher improvisation. The improvisation with plastic animals relied on our pre-assumption that the children were aware that the spontaneous play with plastic animals could be a risk when it comes to learning. Children know that teachers have learning goals with the practice in school. This was also the situation with the children in the project. They knew that the teacher and I had a learning goal with the practice with the animals. Plastic animals as representation for farm-animals and farming, home etc. is not a new concept for the children involved and they do not need much of introduction for performing their knowledge on the theme and material. It is quit easy for them to articulate that the process is about learning what kind of animal it is, how it sounds and were it lives. Therefore, the teacher improvisation was in this context a very low threshold for engagement. As seen in the following pictures (Figs. 1, 2, and 3), the teacher improvisation actually was to set up the play-as learning-situation, and follow the learning flow generated.

Figure 1.

Visual documentation: Bucket and plastic animals; situated teacher idea turned to act. To get the children hooked (same session as mentioned in Scheme 1).

Figure 2.

Visual documentation: First organization made by the children of farm animals. (same session as mentioned in the Scheme 1).

Figure 3.

Visual documentation: Organization made by the children of farm animals after free play with the plastic animals and other artifacts (same session as mentioned in Scheme 1).

When I unite the presented theories on improvisation with the improvisation experiences from the project and render them through the methodology of a/r/tography I find three patterns of meaning (formations) when approaching teacher improvisation. The interpretation of the fusion of theories and experiences conceptualize how improvisation is difficult to explain as something viewed at distance and how it has to be understood through the lived experience that teachers need to be aware of in their practice. There were questions articulated on improvisation in the project: What are the elements of meaning and interest in teacher improvisation practice? How can we better understand the didactic character of improvisation in teaching practice? How do the connections between art and pedagogy practice show when approaching teacher improvisation? At this stage of the process the questions turned into new understanding. The layered researcher experiences scaffold the process of rendering concepts on teacher improvisation. The concepts are here articulated as visual representations since my reflections on the experiences as an artist are highly visual. They directly act upon the research question: What are the elements that can be recognised as teacher improvisation in the project experiences and what implications do they have on the approach to teaching practice?

I approach the representations as elements of improvisation possible to develop and work on together with teachers. The representations are three (new) mindsets: the mosaic, the kaleidoscope and the rhizome (Figs. 4, 5, and 6). These mindsets are elements interpreted in improvisation framed by an education approach on improvisation. They will here be presented as representations in artistic forms that I suggest can be explored for supporting teacher improvisation. The support could be applied within teachers’ approaches to the subject taught, the material used, and in teaching and learning practice including processes from planning to response.

Figure 4.

Teacher’s Improvisation as a Mosaic.

Figure 5.

Teacher’s Improvisation as a Kaleidoscope.

Figure 6.

Teacher’s Improvisation as a Rhizome.

The first representation for recognizing teacher improvisation is the mosaic (Fig. 4.). The mosaic illustrates teachers’ improvisation when they combine ideas for their teaching practice. Teachers combine ideas as repetitive elements in teaching, for observing details in larger learning units. Here, it is important that teachers are given the time needed to rework habits and mindsets. Mosaic representation of teacher improvisation works as a great metaphor supporting teachers to rely on the idea that work during learning processes is as intact as the result that will appear when a school project is completed. This metaphor took its form when the project was planned, when the collaborative conversations were used for elaborating with individual experiences and ideas on what farming, tourism and digital learning could be shaped like in teaching. The mosaic metaphor was given its final form after the project when I was reflecting on all the participants’ experience. I realized that improvisation was the glue that kept together all the concrete material; the artifacts, symbols, and outcomes (mosaic parts) that the teacher, the pupils and I transformed during the process in order to keep the story alive.

The second mindset is represented as a kaleidoscope (Fig. 5). In a kaleidoscope a viewer looks into one end of a cylinder, light is entering the other, and in between there are a lot of tiny objects that mirrors, repeats, colors and changes patterns when rotating. To apply the representation of a kaleidoscope to teacher improvisation is to interpret and understand teachers’ framing of learning spaces as the kaleidoscope, and the movement, the changing patterns as the didactic act. The kaleidoscope was clearly generated on the basis of the professional development questions the teacher and I framed our practice with. Several times we went through our material and created maps including the elements of meanings and interests in understanding teaching improvisation practice. We discussed that the only way to better understand improvisation is to believe that we improvise. We discussed how the connections between art and pedagogy practice show when approaching the practice with education and art theory, the curriculum and new knowledge on how to describe and recognise improvisation.

The third mind set is represented as a rhizome (figure 6). Here, interpreted as an image for improvisation as nomadic didactics, where different impulses in the teaching situation can change the direction, but also the domain, of learning. In a rhizome the power of an impulse can vary as in any didactic act. The rhizome supports the participants (both teachers and pupils) involved to be sensitive enough to react on the impulses as learning and shift of directions and domains in the situation. This is a representation with huge potential for development since it makes it possible to recognize both strong and weak patterns in teacher improvisation.

Featuring an overview of theory and earlier writings on improvisation as part of experiences from a school project, linked with a/r/tographic inquiry and article production turns out to be one way of understanding the elements of teacher improvisation. The three mindsets discovered here were, through an artistic act, transformed to three representations the mosaic, the kaleidoscope and the rhizome. I suggest these as visually communicated findings for approaching teacher improvisation, and thereby a knowledge contribution to understand teacher improvisation. I also suggest that articulating teacher improvisation as artistry. These suggestions offer a possibly very powerful approach for understanding the meaningful practice of improvisation as a source in education. That is one of the most important implications on the outcome here - to actually generate space to articulate improvisation as a very skillful act of the teacher profession: and to do that in a way that communicates teaching artistry.

The aim for this article has been based on theory, and through artist-researcher-teacher research practice, to generate awareness on an activity that many teachers perform; the practice of improvisation. In connecting to Biesta (2013) again, I argue that in order to create a space for pedagogy to unfold, an improvisational space is needed for the teacher. Pedagogy is, and should continue to be, a question of taking risks. To teach is to be human, to accept the fundamental weakness of the purposeful, creative process we call education (Biesta, 2013). Equally, to improvise as teacher is to be human, vulnerable and creative in a one, interconnected, and didactic flow. The mosaic, the kaleidoscope and the rhizome as representations of this flow, I argue, can add to a fuller understanding of the lived experience and pedagogical value of teacher improvisation.

Araujo, J. A. (2012). The a/r/tographic trail. A pedagogigal foothpath. http://theartographictrail.com/. Retrieved May 2016.

Bell, S., Harkness, S., & White, G. (2007). Storyline. Past, present and future. Starthclyde: Enterprising careers.

Biesta, G. (2013). The Beautiful Risk of Education. London & New York: Routledge.

Bishop, C. (2006). Participation. Cambridge: MIT Press.

Bresler, L. (Ed.). (2004). Knowing Bodies. Moving Minds. Toward Embodied Teaching and Learning. Dordrecht: Springer.

Bourriaud, N. (2004). Relational Aesthetics. Dijon: Les presses du reel.

Denhart, R., & Denhart, J. V. (2008). Konsten att leda. En fråga om timing, rytm och kommunikation. Lund: Studentlitteratur.

Dewey, J. (1934). Art as Experience. London: Penguin Books.

Dewey, J. (2010). Taide kokemuksena. Helsinki: Niin Näin.

Dezutter, S. (2011). Professional Improvisation and Teacher Education. In: K. Sawyer (Ed.), Structure and Improvisation in Creative Teaching (pp. 27–50). New York: Cambridge University Press.

Feisst, S. M. (2009). John Cage and Improvisation: An Unresolved Relationship. In: G. Solis & B. Nettl (Eds.), Musical improvisation. Art, education and society (pp. 38–51). Urbana & Chicago: University of Illinois Press.

Goodman, N. (1968). Languages of Art. An approach to a theory of symbols. Indianapolis, US: Bobbs-Merrill.

Irwin, R. L., De Cosson, A., & Pinar, W. F. (Eds.). (2004). A/r/tography: Rendering Self Through Arts-Based Living Inquiry. Vancouver: Pacific Educational Press, University of British Columbia.

Johnstone, K. (1985). Impro. Improvisation and the Theatre. London: Faber.

Kallio-Tavin, M., & Pullinen, J. (Eds.). (2015). Conversations on Finnish Art Education. Helsinki: Aalto University.

Kratus, J. (1996). A Developmental Approach to Teaching Music Improvisation. International Journal of Music Education, 26, 27–37.

Ricoeur, P. (2006). Discours et communication. Paris: Carnets de L’Herne.

Sawyer, K. (2001). Creating conversations: Improvisation in everyday discourse. Cresskill, NJ: Hampton Press.

Sawyer, K. (Ed.). (2011). Structure and Improvisation in Creative Teaching. New York: Cambridge University Press.

Solis, G., & Nettl, B. (Eds.). (2009). Musical improvisation. Art, education and society. Urbana & Chicago: University of Illnois Press.

Springgay, S., Irwin, R. L., Leggo, C., & Gouzouasis, P. (Eds.). (2008). Being with A/r/tography. Rotterdam, Taipei: Sense Publishers.

Toivanen, T., Komulainen, K., & Ruismäki, H. (2011). Drama Education and Improvisation as a Resource of Teacher Students’ Creativity. Procedia, Social and Behavioural Science, 12, 60–69.

1In this article paralleled with characteristics of contemporary art.

2Biesta’s definition of teaching resonates with my understanding of an artistic process.

3For example the characteristics of improvisation in music, dance and theatre.

4The stages are: 1) Exploration, 2) Process orientated improvisation, 3) Product orientated improvisation, 4) Fluid improvisation, 5) Structural improvisation, 6) Stylistic improvisation and 7) Personal improvisation.

5Compare with reasoning on the importance of improvisation and teaching as risk taking earlier in the article.

6The word improvisation is not commonly used as an expression for elaboration in the visual artist professional field.

7In parallel with the research on improvisation I do have a project trying out theories on rhizomatic formations in education.

8Which are represented by the questions constructed by the teacher and myself during the project: What are the elements of meanings and interests in teaching improvisation practice? How can we better understand the didactic character of improvisation in teaching practice? What are the outcomes for the profession? How do the connections between art and pedagogy practice show when approaching the practice in order to promote curriculum and instruction development in improvisation as teaching practice?

9One basis for my approach is my interpretation of Dewey’s argumentations on the role of experience in relation to philosophy, and in particular in my readings of Art as experience (1934). Dewey’s notion that a thought articulated in a scholarly text seems vague when it does not fit your pre-understanding, as appearing vague when you have to put a strong effort into articulating that it is meaningful for this setting (cf. Dewey 1934, 2010).

10An approach to teaching and learning developed by Bell (2007). The key feature is to work thematically and to build on pupils’ and students’ existing knowledge on the subject. The approach supports inquiry based learning, where pupils and teachers together develop ideas on a learning subject.

11Authors free translation from the Swedish project title Gårdsturism. Från hemgård till hemsida.