Introduction

In this new materialist study, I investigate children’s encounters with abstract art as material and embodied pedagogy by focusing on material–relational situations. Two groups of 5–7-year-olds visit an abstract modernist art exhibition that I curated in 2020 for the Children’s Art Museum, a section dedicated to children inside Sørlandets Art Museum in Kristiansand, Norway.1 Nordic post-war abstract art from the Tangen Collection2 was displayed together with activities and digital solutions. The museum educational setting emphasised experimentation, movement and multisensory experiences with abstract art. Art is not only read as representations of different canons in art history but approached as openings for material–relational situations that bring new understandings to light.

Several studies in museum education and closely related fields that use post approaches, such as post-humanisms and new materialisms (Booth, 2017; Feinberg & Lemaire, 2021; Grothen, 2021; Hackett et al., 2018; Medby & Dittmer, 2020; Sayers, 2015) and decolonial theories (Mulcahy, 2021; Rieger et al., 2019) have been published in recent years. For example, Feinberg and Lemaire (2021) write about pedagogical approaches to guided visits in museums that emphasise embodied knowledge and affective responses. Grothen’s (2021) doctoral thesis explores visitors’ experiences in art museums and the question of how to access such knowledge with a theory derived from Deleuze and Guattari (1980/2004). A special issue of Children’s Geographies (Hackett et al., 2018) focuses on children’s presence and learning in museums from embodied and material perspectives.

The present text has a focus on museum educational situations with abstract art. Little attention has been paid to material–relational and multisensory encounters with abstraction, with recent studies focusing mainly on meaning-making through language, such as a dialogue in a gallery space or other text-based learning tools (Dima, 2016; Hubard, 2011; Pierroux, 2005; Scott & Meijer, 2009). Although some studies include abstract art as examples when discussing embodied learning (Hubard, 2007; Roldan & Ricardo, 2014), they do not pay further attention to abstract art.

Focus of this article

My aim is to study how material and embodied pedagogy, underpinned by new materialisms, opens perspectives for learning when children encounter abstract art in a museum space. First, I introduce the material and embodied pedagogy underpinned by new materialisms, according to Page (2018, 2020), and the concept material–relational situation, which I form from the writings of Page (2018, 2020) and von Hantelmann (2014). This is followed by describing my methodological approach, inspired by visual ethnography (Pink, 2021) and the use of action and stationery cameras in the study. Next, I present the experimental exhibition, the concrete research design and ethical considerations. By analysing four material–relational situations, I investigate how learning takes place when the children experiment with abstract art in the museum educational setting.

Embodied and material pedagogy underpinned by new materialisms

New materialist theories understand matter not as passive substance but as agential, relational and unpredictable, constantly changing and becoming (Coole & Frost, 2010; Page, 2018). In acknowledging matter this way, new materialisms offer an alternate understanding of human and non-human relations and pedagogy. The entanglements of the body and matter are a way to learn from and with the world (Page, 2020). My new materialist approach in this study is inspired by the writings of the artist–researcher and teacher Page (2018, 2020), the art historian Kontturi (2018) and the artist and art educator Salminen (1939–2003).3

While new materialisms were not yet an established paradigm, Salminen (2005) offers thoughts about art and art education in texts published in the 70s, 80s and early 90s, which, I suggest, can be described as new materialist. Salminen (2005) criticises dogmas in educational philosophies and wider society that new materialisms are questioning today. Knowledge gathered by the senses is regarded as less important than mathematical and verbal knowledge if it is understood as knowledge at all. Acquiring knowledge in the world does not occur only numerically and verbally, but also nonverbally and alogically through the senses. Visual art and art education develop the skills to understand and find meaning in the world that we can perceive through the senses.

Salminen (2005) refers to the ecological psychologist Gibson (1966) when arguing for the importance of the body in (art) education. Gibson showed that when humans perceive their surroundings, they do not first perceive the qualities of objects, but their affordances: the abilities and opportunities the object has for action. Perception is therefore uninterruptedly connected to its environment (Gibson, 1966, as cited in Salminen, 2005). Furthermore, eyesight is always connected to the other senses, and the eyes are in constant movement. Salminen (2005) writes that perception is not “a forever present-tense cut from the timeline”, as is traditionally thought, but is instead a continuous process in time and space (p. 83). These thoughts further an argument for movement in the exhibition space: embodied pedagogy in museum education. This encourages the use of the whole body and its senses in space when experiencing paintings and other forms of art.

Page (2018, 2020) develops a new materialist theory of pedagogy: an embodied and material pedagogy. Although Page writes in a higher education context, she encourages the use of the theoretical approach in all learning environments. She explores “how materials teach us and how we learn through and with the body” (Page, 2018, p. 1), positioning the body as a source of knowledge. Learning occurs when we participate with our bodies in a sociomaterial world. Multisensory experiences become knowledge on how to live and engage with our environments.

Embodied pedagogy happens together with material pedagogy. Agential matter teaches us with its movements and surprises. It “inspires and demands attention, and through engagement with matter, new modes of practice transpire” (Hickey-Moody & Page, 2015, p. 16). What happens between our bodies and matter, the entanglements of bodies and the world, or intra-action according to Barad (2007), is what Page (2018, 2020) calls pedagogic. This question has also been studied by other researchers in posthuman educational research (e.g., Murris, 2016; Plauborg, 2018; Taylor, 2013, 2020).

Artworks are not only representations of art historical canons. I approach them as material–relational situations that happen like events. I build this concept from two sources: the material–relational comes from the material and embodied pedagogy after Page (2018, 2020), and the situation is derived from von Hantelmann (2014). von Hantelmann argues that the experience of the spectator has become an integral part of the artwork’s conception since the 1960s. Artwork is no longer understood as an object bearing meaning but as a situation experienced by the spectator. This notion blurs the traditional lines of the subject and object, focusing on the situation and performative actions in museum educational encounters. I propose that subjects and objects remain, but that the lines are moving and transient.

Following the theories of critical pedagogy (Freire, 1970; Giroux, 2003; hooks, 1994), Page (2018) criticises pedagogies in which teaching and learning are regarded as passive transmission of knowledge from the teacher to the learner. When one focuses on material–relational situations instead, it becomes less difficult to question dominating understandings. I argue that the interplay between the teacher and the learner and human and non-human matter is not a linear dialogue from A to B, but a rhizomatic (Deleuze & Guattari, 1980/2004) situation of becoming matter (Kukkonen, 2022). Given that the focus lies on intra-action between bodies and matter instead of static entities and top-down linear transmission of knowledge, dominant roles, beliefs and practices become easier to challenge. Embodied and material pedagogy can therefore offer sites of emancipation and transformation and can contribute to democracy and citizenship (Page, 2018).

Visual ethnography

My methodological approach is inspired by visual ethnography, according to the social anthropologist Pink (2021). I wanted to make video recordings to study the relations between children, artworks, activities and the space in detail. Visual ethnography offers a way to understand those aspects of experience that are “sensory, unspoken, tacit and invisible” (Pink, 2021, Visual Ethnography and the Sensory Turn section, para. 1). The approach abandons the idea of text as a superior medium of ethnographic representation, arguing that images should be regarded as equally meaningful (Pink, 2021).

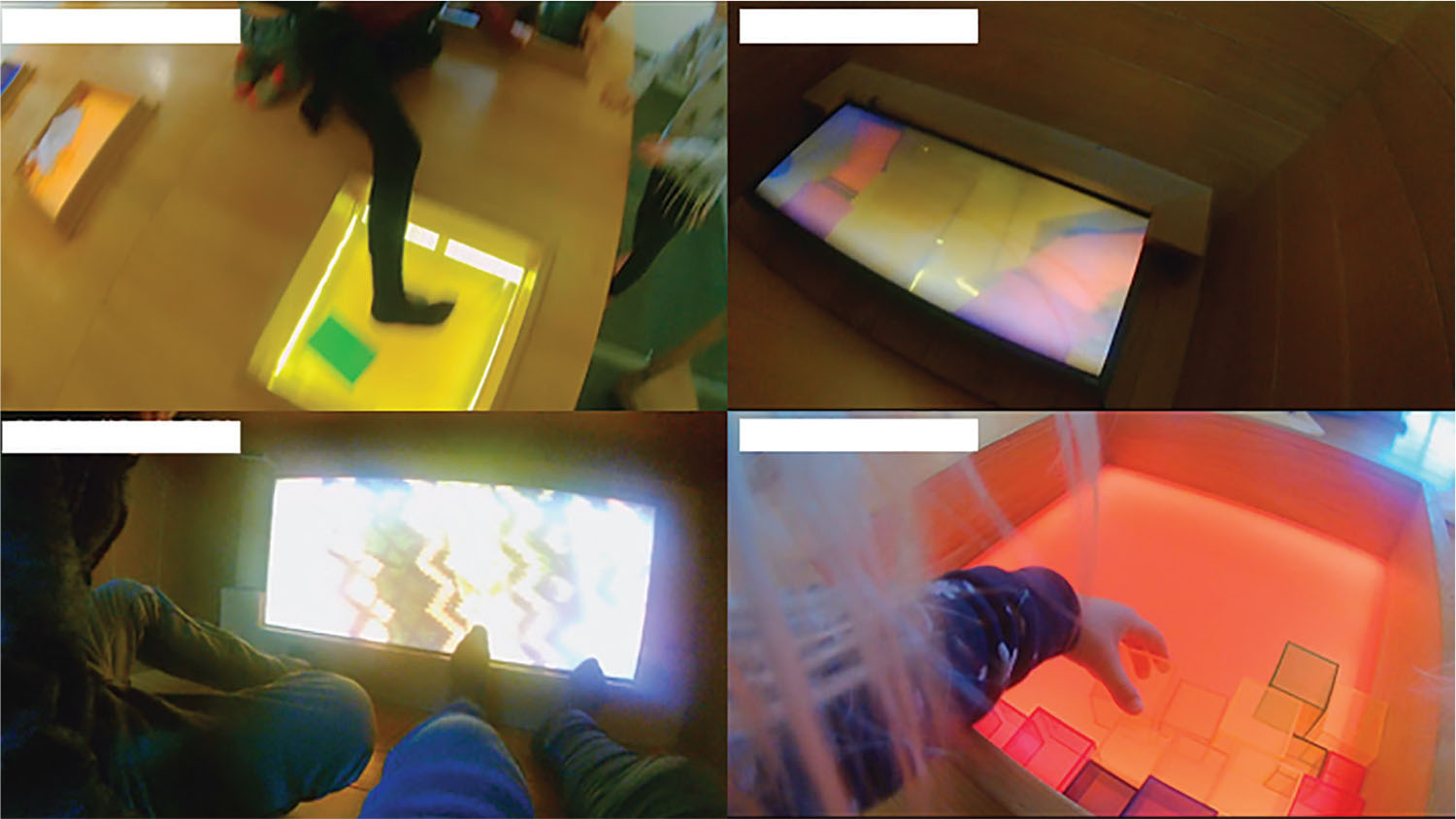

Considering that the complex exhibition space is difficult to film with only stationery cameras, I used three additional action cameras attached to vests that the children wore during the visits. Several studies discuss body-mounted technologies as data gathering tools (e.g., Caton, 2019; Hov & Neegaard, 2020; Lahlou, 2011; Lofthus & Frers, 2021; Pink, 2015, 2021; Vannini & Stewart, 2017). Given that I used both stationery and action cameras, some situations were filmed multiple times. When I watched the video material, I noticed how much the action camera could confuse the situations for the viewer of the film. For example, the body-mounted camera does not show the face of the person wearing the camera, making it challenging to distinguish voices and understand expressions. A clatter soundscape is created when the camera bumps constantly into the clothing of the child wearing the camera and different materials in the exhibition space. I also became more aware of my limits as an adult and a researcher in understanding children’s experiences when I watched the video material. I noticed many meaningful things happening in situations that seemed chaotic from my adult perspective during filming.

Pink (2015, 2021) and Lahlou (2011) describe the body-mounted camera perspective as a “first-person-perspective”. Hov and Neegaard (2020) write that “GoPro action cameras can provide natural data from a child’s perspective” when the action cameras are attached to vests and worn by children (p. 15). Although I agree that body-mounted technology can provide closeness to the participants and the situations, I align my thoughts with studies that critically discuss understandings that privilege the human subject, noting that the action camera is part of a hybrid (Lofthus & Frers, 2021) or an assemblage (Caton, 2019) encompassing human and non-human agencies. The camera, the participants, the researcher (both during and after filming) and the material environment where the filming takes place all have agency in the process and can be seen as co-producers of the perspective.

Museum educational setting at the Children’s Art Museum

Christensen-Scheel (2019) detects two overlapping paradigms in today’s museum education: critical and experiential traditions. She states that the museum education in Scandinavia and elsewhere in Europe leans towards the critical tradition, based on critical philosophy and art’s aesthetic autonomy, drawing from the writings of Kant (1790/2007) and Adorno (1970/2013). An example of the critical tradition is a guided tour that emphasises art historical and biographical knowledge and pays less attention to senses and the visitor’s experience.

In recent decades, many Scandinavian institutions have developed their educational practices towards more experimental settings (Illeris, 2015). Relational and performative approaches (e.g., Aure, 2011, 2013; Aure et al., 2009; Illeris, 2006, 2016; Skregelid, 2019), as well as the post approaches in museum education, challenge the traditional setting by focusing on situations instead of passive transmission of knowledge from teachers to learners, inviting visitors to participate in activities and multisensory encounters with art. I have elsewhere described in detail how I moved from traditional practices towards experiential museum education when I curated the Abstraction! exhibition (Kukkonen, 2022).

The Children’s Art Museum encompasses three rooms and a walk-in climbing cabinet. The space has permanent wooden installations where children can roam around artworks that are inside see-through showcases (Figure 1). My curatorial plan was to create a space where visitors can explore abstraction with their bodies, senses and action (Figure 2). The activities are open in the sense that there are no pre-determined right answers, but a laboratory space for experimentation. The wall texts provide an art historical context, together with philosophical questions that encourage the visitor to philosophise with abstract art. The Abstraction! exhibition took place in many spaces, but my focus in this article is on two rooms.

The first room displays two abstract paintings from the Finnish-Norwegian artist Irma Salo Jæger: Breakthrough (1965) and The Wellspring appears (1961) (see Figures 6 and 7). Both paintings, made with oil paint on canvas, are from the early years of Salo Jæger’s career. The large works have thick layers of paint and rectangular forms. Colours inspired by the paintings are installed on the cabinet boxes with lights shining through the coloured sheets. The wall text about Salo Jæger’s art encourages visitors to pay attention to the agency of the material–relational paintings (Figure 3). The philosophical questions challenge visitors to think about the materiality of colours.

The children receive a canvas bag with coloured plastic sheets and cubes when they enter the room (during the visits, I handed the bags and told the children that they can use the insides to explore abstract art). Visitors can build their own abstractions by experimenting with lights and colours on the large wooden cabinet. One of the built-in boxes contains an action camera, and the spontaneous artwork appears on two screens under the cabinet (see Figure 1). The digital element adds movement and unexpectedness to the art making, given that visitors cannot create and see the result at the same time. It also encourages collaboration: Some can perform, and others can watch and guide the art making.

On the other side of the Children’s Art Museum, Vladimir Kopteff’s (1932–2007) and Outi Ikkala’s (1935–2011) geometrical abstract art is displayed on a wall and in a glass cabinet. A large replica of Kopteff’s Serigrafia IV (1974) is installed on the floor (Figure 4). The carpet functions like a game of Twister, inviting children to invent their own rules and play with the abstract patterns of the life-sized board game. The wall text next to Ikkala’s art challenges the visitor to pay attention to the complexity of our perception and imagination and to test the ideas out (Figure 5).

Research design and ethical considerations

Primary school students in first and second grade (5–7-year-olds) participated in the project. The project plan was approved by the Norwegian Research Council of Research Data before I contacted the school. Two groups encompassing ten and six children, one teacher, two teacher assistants and a person working at the museum, participated in the study. The participants (and the parents/guardians of the children) received an information letter and signed a letter of consent. I met with the teacher, one of the teacher assistants and the museum worker before the visits. We discussed possible problematic situations when it might become necessary to stop filming, and we tested how the action cameras work.

The groups visited the exhibition on separate days. The visits were filmed with three stationary cameras and three GoPro cameras. When the group arrived at the museum, I and the museum worker welcomed the group. We introduced ourselves and discussed the purpose of the visit and the research project in a way that was possible for the children to understand. Why are we here today, and why do we have cameras filming during the visit? What does it mean to research something and what do I research? I told the children that the space has “abstract art, paintings with lots of colours and forms,” and that they can investigate further in the exhibition what abstract art can be.

The children who had consented to wear an action camera were then assisted to put on vests, and I briefly explained how the action cameras work. To set the children’s focus more on the exhibition than the filming, I emphasised to them that the cameras film “by themselves” and do not need special attention. However, this might be ethically problematic, given that such encouragement might make the children forget that they are wearing cameras. As explained by Hov and Neegaard (2020), if children forget that they are wearing cameras, they might say and do things without full understanding that the actions are being recorded and analysed by researchers, which raises the question of consent.

The children were divided into groups of three or four, starting from different rooms. They were then free to move in and between the spaces at their own pace, spending 30–45 minutes in the exhibition. Most of the time, I observed the situation silently. Sometimes I started a conversation with the children, or they engaged me by asking questions or showing me what they were doing. The teachers’ role was to be present in the space, and they could participate in the children’s activities when they wanted to.

The children were encouraged throughout the visit to tell an adult if something is wrong, and I paid special attention to the children’s body language. As Robson (2011) notes, children do not have the same verbal skills as adults to express themselves, which is why the researcher must be attentive to the children’s body language as well to detect possible discomfort. However, I found this challenging since I did not know the children and their personal ways of expressing themselves from before.

“Glowing” data—four material-relational situations

Next, I analyse four situations from the children’s encounters with abstract art as material—relational situations. The situations are all moments that have stayed on my mind after filming and watching the videos, sometimes troubling me, which resulted in including them in this study. I consider these moments as data that “glow;” according to MacLure (2013):

Data have their ways of making themselves intelligible to us. This can be seen, or rather felt, on occasions when one becomes especially ‘interested’ in a piece of data – such as a sarcastic comment in an interview, or a perplexing incident, or an observed event that makes you feel kind of peculiar. (pp. 660–661)

Something material–relational happens in the situations, which, I argue, creates important sites of learning, both for the participants and me as a museum educator, researcher and the curator of the setting. The situations challenge more traditional patterns, where the expert museum educator mediates knowledge about an art object, privileging rational, pre-determined understandings, and the child listens and learns. As mentioned above, I have previously worked mostly with traditional museum educational practices. Although the Children’s Art Museum and my curatorial plan focus on experimentation, and the situations are analysed from a new materialist perspective, I continue to recognise the more traditional museum education taking place in my expectations and reactions. I believe that the “glowing” data trouble those patterns of thinking.

Philosophical questions as openings to material–relational situations

Four children enter the space and walk towards the large paintings, leaning their heads backwards to see them better. Their eyes move upwards from the paintings towards the sculpture in the corner. One of the children addresses me when I enter the room (Figure 6). She points at the “Breakthrough” painting from Irma Salo Jæger and asks with a clear voice, “Can I go into the artwork?” I get confused, and she repeats the question. We look at the painting again, and now all the children are following our conversation. “No … I mean, can you?” I answer. She takes steps closer to the painting and says, “Yes, we can try?” Then, she smiles, shrugs her shoulders and looks at the painting with a wondering look on her face.

The girl herself did not seem to think that the question, which surprised and confused me, was strange at all, asking and repeating it with genuine immediacy and curiosity. As I struggled to answer her, I imagined the absurd idea of children flying inside the painting, and my first impulse was to remind the children not to touch the art. However, I soon understood that the question provoked by the painting was philosophical and playful, not concrete but abstract, and that answering it by rationalising and instructing her would miss the point of the conversation. The question itself is a way of going into the artwork—by engaging and interacting with the painting. In the next paragraphs, I will regard the moment as a material–relational situation.

The museum educational setting where the situation happened blurred the traditional lines of the museum visitor and the art, the subject and the object. Instead of asking the children to sit still on the floor while learning (conversation) takes place (a common practice when groups of children visit exhibitions), the setting encouraged the children to actively move around and to look at the paintings from different angles. They were encouraged to create their own abstract compositions in the space, which also blurred the lines between the artist and the audience. In addition to these elements, the colours and forms of the wooden installation resembled Salo Jæger’s paintings on the wall, creating an immersive learning space. Several children paid attention to the immersiveness during the encounters, commenting on the resemblance of the paintings and the installation (It looks like we can go into the artwork!). The educational setting was built on situations and action rather than the separation of subjects (visitors) and objects (paintings) (Kukkonen, 2022).

The question asked by the girl can be understood as ontological contemplation about art, a big philosophical question that children are talented in asking (Olsson, 2013). Although the question can easily be regarded as absurd, I propose that it is very relevant to learning. Where does the painting begin and end? Where do I begin, and where do I end? What can I do and not do with the artwork? The question is curious and challenges the obvious presuppositions. I used similar philosophical questions in the exhibition texts to encourage visitors to wonder and philosophise (What are colours made of? Can you see with your eyes closed?). The paradoxical questions do not have fixed right or wrong answers but demand complex understandings. The visitor is playfully challenged with mind-meddling questions; if the situation has no playfulness and becomes too serious, the visitors will most likely lose their interest.4 Playfulness makes it possible to experiment, test out new understandings and see things from multiple perspectives, given that no actual risk of failure exists.

Can I go into the artwork? From the perspective of new materialisms, an artwork is understood more as a material–relational situation than as a static and mute object. Paintings are often approached in their “still finalities”, but they also have movement: “Brushstrokes have their rhythm, paint cracks quietly” (Kontturi, 2018, p. 9). The children take steps closer and further away from the painting; they arch their backs and lean their heads backward. Page (2018) writes how material and embodied pedagogy happen through the entanglements of subjects and objects in the event and actions. I argue that the question asked by the girl is this action between and the entanglement of subject and object. The painting becomes an opening for intra-action and play—a material–relational situation.

Breaking patterns through artmaking

A boy looks into his canvas bag. “What are we supposed to do?,” he asks. He begins to follow the others who are sorting out the components in the big squares on the wooden installation according to their colours. His friend holds a green sheet in his hands, looking around the room (Figure 7). “Where is the green box?” Two others negotiate where the violet cubes should go—there are no green or violet boxes. Then, one of them begins to read the instruction sheet found in the bag, slowly spelling the text. “We will make ART here!,” he announces loudly to the others. They all look surprised, looking around the room with round eyes. “Let’s gather all the cubes and sheets into this box,” a girl says. She turns around the canvas bag in her hands, and all the components left in the bag fall into the box.

A similar situation, which I had not expected, happened four times during the filming. Children enter the room and begin to sort out the colours. It becomes a play; they exchange sheets and cubes and help each other out in the sorting process. They all face the same problem: there are no boxes for violet or green components, and they begin to negotiate where these could be placed. The situation changes completely when they find out that they can make art in the space (either the children manage to read the instruction sheet themselves, or I or the teacher reads it to them, when we notice that they cannot read the note). Suddenly, they need all the colours, also the green and violet, and begin to mix them in and outside of the boxes.5

It is noticeable how the children who participated in the artmaking understand the concept of art as an opportunity to break and mix the sense-making patterns. They are suddenly allowed to experiment, and they no longer pursue sorting and organising according to already-known logical patterns. The children begin to create their own abstract artworks that grow out of the boxes. Salo Jæger’s paintings, where the shattered forms and colours mix into each other, hang on the wall, epitomising the experimental qualities of art. O’Sullivan (2006) writes that art is an entry point to see beyond the recognisable and reassuring, “a line of flight from representational habits of being” (p. 30). Salminen (2005) also writes how art’s task is to scrutinise and dismantle cliches and “saturated thoughts” (p. 186). New materialisms (e.g., Kontturi, 2018) and material and embodied pedagogy (Page, 2018) encourage to follow the movements of materialities—to engage with the world with the body instead of observing and analysing it from a distance. I argue that artmaking in the space entangled the children closer to the space and abstraction, encouraging them to experiment instead of repeating what they already knew.

Experimenting with human and non-human matter

A girl is creating artwork on the yellow box. She places cubes of different sizes and colours on the lower side of the box, carefully adjusting them to their place. Someone tries to change the composition, but she stops him. There seems to be a plan that takes place even if the order of the cubes seems arbitrary. She goes to look at the screen to check what the composition looks like. “I will make a fine artwork …,” she says and grabs her striped wool shirt. The girl sets the sweater on top of the yellow box, and stripes and patterns appear on the screen below the wooden installation (Figure 8).

Kontturi (2018) writes that experimentation is “relational matter in movement, in transformation. Matter as intensity is not a calculable quantity, but a quality that can only be experienced – and experimented with” (p. 39). In the situation above, the girl’s own sweater–matter decorated with abstract patterns transforms into artistic matter in the experimentation. During the encounters, not only the designated materials but also the extra clothes, as well as the canvas bags and instruction sheets, became part of the abstractions. While art making is always embodied, the matter of human bodies becomes artistic matter as well in a very concrete way, when the children adjust their hands, feet and faces into the box with the other components (going into the artwork!). However, art making is not only wild experimentation or “anything goes.” “Aesthetic intuition” seems to take place, even in the most abstract compositions. The children compose the pieces carefully and deliberately in their places. The “order” that takes place is not logical, but intuitive, aesthetic and visual.

Hickey-Moody and Page (2015) write that matter “shows us the limits of the world as we know it and prompts us to shift these limits” (p. 5). The children come across the limits of the space and their bodies: someone bumps on the composition, the children agree and disagree on how the composition should be built, and the camera and the screen change the colours and proportions of the composition. The boxes are slightly tilted so that the sheets and cubes slide down here and there, causing the children to change their artworks or find ways to keep them in place. Wearing soft fabrics, their bodies slide down the smooth wooden installation as they try to adjust their assemblies. The compositions appear on the screen below the installation, and they need to climb down or collaborate with others to see what their experiments look like. The children come up with creative solutions, pushing the limits of the space and their bodies further. They place their feet on the box and hang their heads upside down from the window to see their feet appear on the screen (Figure 8). When they cannot reach the window or the screen, they ask a friend or teacher to check the screen for them, and they begin to build the compositions together.

Showing their artworks to each other becomes an important part of the process (Figure 8). Looking at the artworks appearing on the screen brings joy—the children laugh and change roles again (the composer becomes the spectator and vice versa). Salminen (2005) writes how art education’s task is to show that being creative does not need to be pompous, overly strange or a continuous vortex of breath-taking emotions. The enjoyment is often created when old and familiar is seen in a new light and newly discovered through someone else’s eyes, communicated through art. Art is relational, “not just saving to one’s own piggy bank” (Salminen, 2005, p. 186). When the children experiment with their abstractions, show their abstractions to others, see them appear on the screen, as well as when the sweater–matter and human-matter become artistic matter, something is seen in a new light, entangled in a new way. The matter “shows them otherwise” (Hickey-Moody & Page, 2015, p. 16). I suggest that this is also the aspect of art that the new in new materialisms points out to—the continuous processuality and the unpredictable unfolding of any materiality (Kontturi, 2018; Tiainen et al., 2015).

Matter teaching children and adults

A teacher reads a wall text about the artist, Vladimir Kopteff. She steps on the large replica on the floor where the children are hopping and playing on the abstract patterns. Then, she takes a hesitative look inside the mirror cabinet with abstract geometrical art. She looks confused, amused and a bit uncomfortable. When one of the children approaches her, she begins to laugh and says, “Have you seen how strange it is here? So strange!” The student looks at the teacher with a blank expression; he does not seem to understand what makes the space so strange. Then he asks the teacher to come with him. The teacher follows the child through the three rooms, looking around, while the boy presents the spaces for her.

Page (2018) writes how the positions of teacher and learner are continually renegotiated in material and embodied pedagogy, making it possible to find new ways of making, teaching and learning. The positions of teacher and learner not only concern the human bodies but also how different materialities become the “teacher” when entangled with humans. Therefore, in the situation above, I find it not only intriguing how the child becomes the teacher for the adult but also how differently the child and the adult relate to the “teaching” material environment.

The adult seems confused and slightly uncomfortable in the museum educational setting. While I cannot exactly know what the teacher was thinking in the situation, I suggest that the strangeness might come from the material and embodied pedagogy (the artistic matter is on the floor and inside the cabinet, and the children are encouraged to explore the space with their whole bodies, unlike in a more traditional museum space). The setting does not comply with the expectations of the adult, and she seems to expect a similar reaction from the child. However, the space is not strange for the child, only for the adult, so the child begins to help the adult understand what is going on in the exhibition.

The material and embodied pedagogy seems to be more familiar to the child than to the adult. I suggest that children might be more open to entanglements with the material world than adults, exploring the world more with their senses and bodies than adults in general. The researcher Rautio (2013) makes similar remarks, using Bennett’s (2010) concept of aesthetic–affective openness:

Children, by virtue of their both biophysical and socially/culturally constructed existence, often seem to apply what Bennett (2010) describes as aesthetic–affective openness towards material surroundings: an attentiveness to and sensuous enchantment by non-human forces, an openness to be surprised and to grant agency to non-human entities (see also Harker 2005). (p. 395, original italics)

The museum educational setting can be an important site for learning, not only for children but also for adults who might not be as open to the teaching matter in general.

Conclusions

In the present text, I analysed four situations from the children’s encounters with abstract art at the Children’s Art Museum, studying them as material–relational situations. To my knowledge, museum educational situations with abstract art have not been studied before to the same extent from a new materialist perspective. This study contributes to the new but growing field of post-approaches in museum education, knowledge that has been called for in previous research (Hackett et al., 2018; MacRae et al., 2018). In the first situation, I argued that a paradoxical question asked by a child becomes an opening for intra-action and play, entangling the object and subject. In the second situation, artmaking appeared as an opportunity to break logical patterns. However, the breaking of patterns becomes a pattern as well, and while the abstractions made by the children are not created logically, an “intuitive-aesthetic order” takes place, something I wish to study further.

Human and non-human matter transformed into artistic matter when the children experiment in the space, bringing new understandings to light. The last situation showcases the “teaching matter” as agentive teacher and how differently children and adults might relate to it. It would be interesting to pay more attention to the experiences of adults, who might have a steeper learning curve with abstract art, in future studies. Embodied and material pedagogy with abstract art indicates how “making sense” in the world is not only done by verbal, logical and rational ways, but by engaging with bodies and senses, and most importantly, letting the matter teach, too.

References

- Adorno, T. (2013). Aesthetic theory. (R. Hullot-Kentor, Trans.). Bloomsbury. (Originally published 1970)

- Aure, V. (2011). Kampen om blicket: En longitudinell studie der formidling av kunst til barn og unge danner utgangspunkt for kunstdidaktiske diskursanalyser [Conflict of the gaze: A longitudinal study in which mediating art to children and young people forms the starting point for a discourse analysis] [Ph.D. thesis]. Stockholm University.

- Aure, V. (2013). Didaktikk – i spennet mellom klassisk formidling og performativ praksis [ Didactics – between classic mediation and performative practice]. Nordic Journal of Art and Research, 2(1), 1–24. https://doi.org/10.7577/if.v2i1.611

- Aure, V., Illeris, H., & Örtegren, H. (2009). Konsten som läranderesurs: Syn på lärande, pedagogiska strategier och social inklusion på nordiska konstmuseer [Art as a resource for learning: A study of pedagogical strategies and social inclusion in Nordic art museums]. Nordiska akvarellmuseet.

- Barad, K. (2007). Meeting the universe halfway: Quantum physics and the entanglement of matter and meaning. Duke University Press.

- Bennett, J. (2010). Vibrant matter. A political ecology of things. Duke University Press.

- Booth, K. (2017). Thinking through lines: Locating perception and experience in place. Qualitative Research, 18(3), 361–379. https://doi.org/10.1177/1468794117722826

- Caton, L. (2019). Becoming researcher: Navigating a post-qualitative inquiry involving child participants and wearable action cameras [Ph.D. thesis]. Manchester Metropolitan University.

- Christensen-Scheel, B. (2019). Sanselige møter eller kritisk tenkning? Formidling i samtidens kunstmuseer [Sensuous encounters or critical thinking? Mediating art in contemporary art museums]. In C. B. Myrvold & G. E. Mørland (Eds.), Kunstformidling. Fra verk til betrakter [Mediating art – From the object to the spectator] (pp. 22–46). Pax Forlag.

- Coole, D., & Frost, S. (2010). New materialisms. Ontology, agency and politics. Duke University Press.

- Deleuze, G. (1988). Spinoza, Practical Philosophy (R. Hurley, Trans.). City Lights Books.

- Deleuze, G., & Guattari, F. (2004). A thousand plateaus – capitalism and schizophrenia (B. Massumi, Trans.). Continuum. (Originally published 1980)

- Dima, M. (2016). Value and audience relationships: Tate’s ticketed exhibitions 2014–15. Tate Papers, 25. https://www.tate.org.uk/research/tate-papers/25/value-and-audience-relationships

- Feinberg, P. P., & Lemaire, M. (2021). Experimenting interpretation: Methods for developing and guiding a “vibrant visit”. Journal of Museum Education, 46(3), 357–374. https://doi.org/10.1080/10598650.2021.1933723

- Freire, P. (1970). Pedagogy of the oppressed. Penguin.

- Gibson, J. (1966). The senses considered as perceptual systems. Houghton Mifflin.

- Giroux, H. A. (2003). Public pedagogy and the politics of resistance: Notes on a critical theory of educational struggle. Educational Philosophy and Theory, 35(1), 5–16. https://doi.org/10.1111/1469-5812.00002

- Grothen, G. (2021). Gjennom museene – møter mellom publikum og kunst [Across museums – Encounters between art and the public] [Ph.D. thesis]. University of South-Eastern Norway.

- Hackett, A., Holmes, R., & Jones, L. (Eds.). (2018). Young children’s museum geographies: Spatial, material and bodily ways of knowing. Children’s Geographies, 16(5), 481–488. https://doi.org/10.1080/14733285.2018.1497141

- Harker, C. (2005). Playing and affective times-spaces. Children’s Geographies, 3(1), 47–62. https://doi.org/10.1080/14733280500037182

- Hickey-Moody, A., & Page, T. (2015). Introduction. In A. Hickey-Moody & T. Page (Eds.), Arts, pedagogy and cultural resistance. New materialisms (pp. 1–20). Rowman & Littlefield International.

- Hooks, B. (1994). Teaching to transgress. Education as the practice of freedom. Routledge.

- Hov, A. M., & Neegaard, H. (2020). The potential of chest mounted action cameras in early childhood education research. Nordic Studies in Science Education, 16(1), 4–17. https://doi.org/10.5617/nordina.7049

- Hubard, O. M. (2011). Illustrating interpretative inquiry – a reflection for art museum education. Curator: The Museum Journal, 54(2), 165–179. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.2151-6952.2011.00079.x

- Hubard, O. M. (2007). Complete engagement: Embodied response in art museum education. Art Education, 60(6), 46–56. https://doi.org/10.1080/00043125.2007.11651133

- Illeris, H. (2006). Museums and galleries as performative sites for lifelong learning: Constructions, deconstructions and reconstructions of audience positions in museum and gallery education. Museum and Society, 4(1), 15–26. https://journals.le.ac.uk/ojs1/index.php/mas/article/view/75/90?acceptCookies=1

- Illeris, H. (2015). The friendly eye: Encounters with artworks as visual events. In A. Göthlund, H. Illeris, & K. W. Kristine (Eds.), EDGE: 20 essays on contemporary art education (pp. 153–168). Multivers Academic.

- Illeris, H. (2016). Learning bodies engaging with art: Staging aesthetic experiences in museum education. International Journal of Education Through Art, 12(2), 153–165. https://doi.org/10.1386/eta.12.2.153_1

- Kant, I. (2007). Critique of judgement (N. Walker, Ed.) (M. J. Creed, Trans.). Oxford University Press. (Originally published 1790)

- Kontturi, K. (2018). Ways of following. Art, materiality, collaboration. Open Humanities Press.

- Kukkonen, H. (2022). Abstraction in action: Post-qualitative inquiry as an approach to curating. In L. Skregelid, & K. Knudsen (Eds.), Kunstens betydning utvidede perspekrtiver på kunst oh barn & unge (s. 319–342). Ceppelen Damm Akademisk.

- Lahlou, S. (2011). How can we capture the subject’s perspective? An evidence-based approach for the social scientist. Social Science Information, 50(34), 607–655. https://doi.org/10.1177/0539018411411033

- Lofthus, L., & Frers, L. (2021). Action camera: First person perspective or hybrid in motion? Visual Studies, advance online publication, 1–13. https://doi.org/10.1080/1472586X.2021.1878055

- MacLure, M. (2013). Researching without representation? Language and materiality in post-qualitative methodology. International Journal of Qualitative Studies in Education, 26(6), 658–667. https://doi.org/10.1080/09518398.2013.788755

- MacRae, C., Hackett, A., Holmes, R., & Jones, L. (2018). Vibrancy, repetition and movement: posthuman theories for reconceptualizing young children in museums. Children’s Geographies, 16(5), 503–515. https://doi.org/10.1080/14733285.2017.1409884

- Medby, I. A., & Dittmer, J. (2020). From death in the ice to life in the museum: Absence, affect and mystery in the Arctic. Environment and Planning D: Society and Space, 39(1), 176–193. https://doi.org/10.1177/0263775820953859

- Mulcahy, D. (2021). A politics of affect: Re/assembling relations of class and race at the museum. Emotion, Space and Society, 39(1), 1–7. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.emospa.2021.100773

- Murris, K. (2016). The posthuman child. Educational transformation through philosophy with picturebooks. Routledge.

- Olsson, L. M. (2013). Taking children’s questions seriously: The need for creative thought. Global Studies of Childhood, 3(3), 230–253. http://dx.doi.org/10.2304/gsch.2013.3.3.230

- O’Sullivan, S. (2006). Art encounters deleuze and guattari. Thought beyond representation. Palgrave MacMillan.

- Page, T. (2018). Teaching and learning with matter. Arts, 7(4), 1–12. https://doi.org/10.3390/arts7040082

- Page, T. (2020). Placemaking: A new materialist theory of pedagogy. Edinburgh University Press.

- Pierroux, P. (2005). Dispensing with formalities in art education research. Nordisk Museologi, 2, 76–88. https://doi.org/10.5617/nm.3316

- Pink, S. (2015). Going forward through the world: Thinking theoretically about first person perspective digital ethnography. Integrative Psychological & Behavioral Science 49(2), 239–252. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12124-014-9292-0

- Pink, S. (2021). Doing visual ethnography. Sage Publications.

- Plauborg, H. (2018). Towards an agential realist concept of learning. Subjectivity: International Journal of Critical Psychology, 11(4), 322–338. https://doi.org/10.1057/s41286-018-0059-9

- Rautio, P. (2013). Children who carry stones in their pockets: on autotelic material practices in everyday life. Children’s Geographies, 11(4), 394–408. https://doi.org/10.1080/14733285.2013.81227

- Rieger, J., Kessler, C., & Strickfaden, M. (2019). Doing dis/ordered mappings: Shapes of inclusive spaces in museums. Space and Culture, 25(1), 4–19. https://doi.org/10.1177/1206331219850442

- Robson, S. (2011). Producing and using video data in the early years: Ethical questions and practical consequences in research with young children. Children & Society, 25(3), 179–189. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1099-0860.2009.00267.x

- Roldan, J., & Ricardo, M. (2014). Visual a/r/tography in art museums. Visual Inquiry, 3(2), 172–188. https://doi.org/10.1386/vi.3.2.172_1

- Salminen, A. (2005). Pääjalkainen. Kuva ja havainto [Tadpole people. Image and perception] (I. Koskinen, Ed.). Aalto University, School of Arts, Design and Architecture.

- Sayers, E. (2015). From art appreciation to pedagogies of dissent. Critical pedagogy and equality in the gallery. In A. Hickey-Moody & T. Page (Eds.), Arts, pedagogy and cultural resistance. New materialisms (pp. 133–152). Rowman & Littlefield International.

- Scott, M., & Meijer, R. (2009). Tools to understand: An evaluation of the interpretation material used in Tate Modern’s Rothko Exhibition. Tate Papers, 11. https://www.tate.org.uk/research/publications/tate-papers/11/tools-to-understand-an-evaluation-of-the-interpretation-material-used-in-tate-moderns-rothko-exhibition

- Skregelid, L. (2019). Tribuner for dissens. Ungdoms møter med samtidskunst. Cappelen Damm Akademisk.

- Tiainen, M., Kontturi., K., & Hongisto, I. (Eds.) (2015). New materialisms. Cultural Studies Review, 21(2), 4–13. http://epress.lib.uts.edu.au/journals/index.php/csrj/index

- Sørlandets Art Museum. (2021). Tangen-samlingen – SKMU – Sørlandets Kunstmuseum [Tangen Collection – SKMU – Southern Norway Museum of Art]. https://www.skmu.no/samlingen/tangen-samlingen/

- Taylor, A. (2013). Reconfiguring the natures of childhood. Routledge.

- Taylor, A. (2020). The common world of children and animals: Relational ethics for entangled lives. Routledge.

- Vannini, P., & Stewart, L. M. (2017). The GoPro gaze. Cultural Geographies, 24(1), 149–155. https://doi.org/10.1177/1474474016647369.

- von Hantelmann, D. (2014). The experiential turn. In E. Carpenter (Ed.), On performativity. Vol 1 of Living Collections Catalogue. Walker Art Center. http://walkerart.org/collections/publications/performativity/experiential-turn/

Fotnoter

- 1 Sørlandets Art Museum applied and received funding for the exhibition from AKO Foundation.

- 2 About Tangen Collection, see Sørlandets Art Museum, 2021.

- 3 I thank Irma Salo Jæger for introducing me to Salminen’s writings.

- 4 I align my thoughts with Harker’s (2005) understanding about playing as becoming and difference. Inspired by Deleuze (1988), he highlights the notions of embodiment, affect, objects and time–space as important aspects of playing.

- 5 The artmaking seemed challenging when there were more than four children in the space. Some children begun to sort the colors again after a while. Some did not want to make their own artworks but were motivated to look for sheets and cubes for the others or simply watch the artmaking.