Introduction

We brought markers in different colours, a notebook, a computer, and a speaker. Camera is rolling, ready to document our planning process. We roll out a long brown paper roll. Music fills the room, and we start walking the space, finding its latent opportunities and invisible pathways. No chairs, no tables. Just us and the space with its things that invite bodies to explore movement and different ways of interaction. Opening up for bodily ways of planning. (Bodily narrative, based on log from bodily planning session)

In this article, we describe and analyse our process of creating a series of dance workshops aimed at developing kindergarten teachers’ bodily professional knowledge in a collaboration between a kindergarten teacher educator (Ida) and a somatic dance teacher (Live). The context is an ongoing PhD project (2018–2022) in professional practice at a teacher education department in Norway. The specific focus of the ongoing PhD project is to investigate how kindergarten teachers’ bodily professional knowledge can be understood, articulated, and developed. By bodily professional knowledge we mean the bodily-relational, affective and emotional knowledge which is activated as kindergarten teachers communicate with kindergarten children (Pedersen & Orset, 2020). Focus for this article is the planning process that grew out of our collaborative and art-based approach to planning the workshops. Drawing on a performative research paradigm (Haseman, 2006; Østern et al., 2021), understanding research as creating something new, with the researchers positioned on the inside of the research process, the question that is elaborated in this article is:

How can workshops aiming at developing kindergarten teachers’ bodily professional knowledge be created through a kindergarten teacher educator’s and somatic dance teacher’s arts-based and bodily planning?

In the process, we, the kindergarten teacher educator and the somatic dance teacher, are therefore research participants while simultaneously developing the workshop design, and research material is continuously being created in the process. In this process, we, as authors, are entangled in different ways, and by acknowledging bodily ways of knowing we contribute to the workshop development with complementary knowledges. Ida is well acquainted with dance through research and practice, and Live has studied pedagogy and has long experience as a dance teacher for children and adults. When we say that we are entangled, we refer to Karen Barad’s (2007) agential realism, a theoretical stance that we take in this research. Very briefly, the concept of entanglement implies how phenomena are ontologically inseparable (Barad, 2007). We will return to agential realism later in the article.

Awareness around the youngest kindergarten children’s bodily ways of playing and being in the world has blossomed in research over the last 20 years (Løkken, 2000; Nome, 2017; Øksnes, 2010; Rossholt, 2012; Sandvik, 2016; Ulla, 2015) alongside the bodily turn.1 Also, the material turn2 has influenced early pedagogy (Lenz Taguchi, 2010; Reinertsen, 2016), especially in Nordic research, which is where this project is situated. Many researchers within early pedagogy, such as those mentioned above, fully acknowledge the bodily aspects of the kindergarten profession as well, but there is a lack of research on how this professional bodily knowledge is taught, learned, and further developed. With this study, we seek answers on how to create workshops for this sake.

In the following we present the methodological approach of the study before we offer theoretical perspectives. We then move on to an analysis in two layers. Finally, we discuss and conclude the knowledge contribution.

Methodological approach: Bodily, collaborative, and arts-based research

As mentioned, the methodological approach is based on how we as authors bodily plan dance workshops. Through four bodily planning sessions we created four dance workshops (each lasting 90 minutes) for kindergarten teachers. With bodily planning we suggest how the design team – we met in a dance/yoga space, walking, spinning, talking, touching, writing, drawing, and moving in time and space when creating workshop design. When using the phrase design team we point towards our entangled, bodily and collaborative work. We call the workshops soma-space workshops. Soma broadly means ‘body,’ and the combination of soma and space in soma-space emphasises the bodily and spatial character of the workshops designed. These soma-space workshops are spaces where we can collaboratively explore what bodily professional knowledge might be and how it could be developed. Through our bodily planning we sought to create a space for the kindergarten teachers to stretch bodies, minds and ideas, opening up for bodily professional knowledge development.

Our own logs and video-recordings of the bodily planning sessions, allowing us to revisit our bodily planning, are research material in this article. This material is analysed in two layers: first, reading the research material with Barad’s (2007) understanding of material-discursive entanglements (analytical layer 1), resulting in four entanglements that we suggest as design principles for workshops aiming at kindergarten teachers’ professional development. The second reading (analytical layer 2) introduces the workshop design, theory-infused by Helle Winther’s (2014) embodied professional competence concept and other relevant research within kindergarten pedagogy and somatic dance. The kindergarten teachers’ experience of participating in the workshops is the focus in another article (Pape-Pedersen, 2022). With this article, we explore how the workshops were designed through a bodily planning process to support the development of kindergarten teachers’ bodily professional knowledge.

By using dance and other art forms for researching professional development, we define the workshop planning project as arts-based research. According to Patricia Leavy (2018, p. 4), arts-based research is a transdisciplinary approach to creating knowledge, which combines creative arts with research. Epistemologically, arts-based research assumes that art can create and express meaning (Leavy, 2018, p. 5). This project is based in the belief that thinking happens in movement, and conversely, that movement enhances thinking. Maxine Sheets-Johnstone (2009) emphasises that thinking in movement is foundational to being-a-body. In other words, as we, the design team, move around in space and relate to one another, we think-in-movement (Sheets-Johnstone, 2009), which helps us in making decisions as we bodily plan the soma-space-workshops. Arts-based research further lends itself to aesthetic ways of knowing, which means that sensory, affective, kinaesthetic, embodied, and imaginal ways of knowing are appreciated and seen as pivotal, not additional, to knowledge creation (Leavy, 2018, p. 5).

According to Maggi Savin-Baden and Claire Howell Major (2013, p. 272), collaborative approaches are varied and many, but still, what they have at their heart is an emphasis on transformation, change, participation, and voice. This project shares the emphasis on these aspects by giving the body space in the kindergarten teacher profession, giving kindergarten teachers the possibility to participate bodily and fully in their own professional development. Collaborative approaches as methodology assume that a process of change usually emanates from within a community, in this article a small design team consisting of a kindergarten educator and a somatic dance teacher (Savin-Baden & Howell Major, 2013, p. 261). This design team is bodily, arts-based, and collaboratively on the floor planning, thinking-in-movement (Sheets-Johnstone, 2009), and allowing the holistic body to create the workshop design. Conducting collaborative research means generation of research material that is flexible, half-structured and emerging from within a practice. This resonates well with this study: the research material is constantly being created through the creative processes of planning the workshops. The research materials are emerging and becoming through the four planning sessions where the material is generated.

We collect bodily and collaborative approaches and arts-based research under a performative research paradigm (Haseman, 2006; Østern et al., 2021). In a performative research paradigm research is understood as the creation of something new. The researchers are on the inside of the research process; we influence and are influenced as researcher bodies by the knowledge created. Also, within a performative research paradigm, arts-based expressions are understood as equally important as verbal and written modalities.

To sum up, the research material for this study is produced through four planning sessions by a small design team, with a bodily, arts-based and collaborative methodological approach, positioned under a performative research paradigm. Next, we present theoretical perspective that the study dialogues with.

Previous research and theoretical perspectives

Previous research implies that kindergarten teachers have a bodily knowledge base as part of their professional knowledge (Pedersen & Orset, 2020). However, this requires further investigation, as there is a lack of research for developing this kind of knowledge in early pedagogy, especially on how you can do this through bodily planning. The creation and articulation of the workshop design and design principles in this study we therefore view as a theory/practical knowledge contribution of this work. It is practical in the sense that it can be conducted in practice, and theoretical in that in articulates insights on entangled bodily planning and bodily professional knowledge development.

Bodily knowledge

We see bodily knowledge as a crucial, but overlooked, expertise within kindergarten teachers’ professional practice, and we observe and connect to a growing field of research that investigates and highlights themes such as embodiment in education (Parviainen, 1998; Svendler Nielsen, 2014; Winther, 2014), bodily learning (Østern, 2013), embodied pedagogy (Dixon & Senior, 2011; Forgasz & McDonough, 2017; Sheets-Johnstone, 2009), the pedagogy of listening and the environment as the third teacher as part of an emerging intra-active pedagogy (Åberg & Lenz Taguchi, 2006; Malaguzzi, 1996; Rinaldi, 2006; Taguchi, 2010, Wexler, 2004), in-depth learning (Østern & Dahl, 2019), somatic dance and movement practices (Rouhiainen, 2008; Song & Yun, 2017), and mindfully somatic pedagogy (Buono, 2019). Altogether we see this literature and research cited above as being valuable in the process of developing kindergarten teachers’ professional knowledge.

In this article we aim at creating new insights by entangling early pedagogy, which in this case is professional development within pedagogy for the youngest kindergarten children (0–3 years old), and somatic dance. Somatic dance and movement practices (Buono, 2019; Østern, 2013; Rouhiainen, 2008; Song & Yun, 2017) imply listening in to, nurturing, and creating dance and movement based on subtle bodily processes like breathing and inner bodily states. Through cross-fertilising education, arts, and bodily-material relations as potentials for professional development, we aim at entangling early pedagogy and somatic dance education towards a bodily approach to kindergarten teacher education and professional development. In this, we also reach for a language that creates a space for bodily knowing within academia. This way, we want to contribute with creating both a space and language for bodily knowledge production within the kindergarten education. With that said, we now move on to one of the main theoretical perspectives in this study.

Helle Winther’s movement psychology

Helle Winther (Skovhus & Winther, 2019; Winther, 2008, 2009, 2014; Winter et al., 2015) is a central researcher in combining dance and movement with professional practice. In her movement psychology Winther (2014) presents three important aspects for developing embodied professional competence: (1) self-contact and somatic awareness: a contact to one’s own body and feelings, explained as having the ability to be present, bringing the heart in and at the same time have a professional focus, (2) communication reading and contact-ability: the ability to see, listen and sense what is at stake both verbally and bodily, and make suitable contact with others through movement, and (3) leadership in groups and situations: professional centring, overview and exuberance while communicating with and leading others, like holding a room, in a positive way, with embodied authority (Winther, 2014, p. 80). Winther (2009, 2014) highlights that the personal, the professional, and the embodied are constantly and simultaneously present. In her research, she has, alone and together with other researchers, been writing/dancing in connection with different professions, such as nurses, as presented in the article “The dancing nurses and the language of the body” (Winther et al., 2015), and student teachers in the article “ The development of teacher students’ leadership through body and movement” (Skovhus & Winther, 2019), where the authors specify that every child has the need to meet relation-competent adults/teachers (p. 14). We brought the theory/practice of Winther (2014) in with us when starting the planning sessions. Winther has a research approach where theory and practice intertwine, which also has been essential in our study. We highlight this combination by drawing theory and practice together with a slash; theory/practice. So, in many ways, the design for the soma-space workshops created in this study has traces of and entangles with Winther’s work. Still, we have chosen to use the word “bodily” instead of “embodied” because we want to highlight that the knowledge is bodily; immediate from the affective body, before/in same moment as thinking and reflecting, not embodied; which can indicate that it is first reflected upon on and then, secondarily, made into an embodied expression.

With this as a theoretical background, we now move into the analysis of the research material, seeking to investigate how workshops aiming at developing kindergarten teachers’ bodily professional knowledge can be created through a kindergarten teacher educator’s and somatic dance teacher’s arts-based and bodily planning.

Analysis in two layers

The analysis is, as Barad (2007) calls it, cutting-together-apart in two layers. In the analysis we think with theory (Jackson & Mazzei, 2012), as this can contribute to producing knowledge differently and keep meaning on the move. For us, thinking with theory implies a way of thinking-feeling (Massumi, 1995; Reinertsen, 2016) as body-minded researchers (Maapalo & Østern, 2018) as the creation of new movement suggestions, entangled relations and theoretical concepts becomes a part of the – always ongoing – (bodily) knowledge production.

Analysis layer 1 implies reading the research material with Barad’s (2007) agential realism. The concepts we think-feel (Reinertsen, 2016) this research material (logs and video material from the planning sessions) with are Barad’s ideas of material-discursive entanglements, intra-action, and agential cutting.

In analysis layer 2 we present the workshop design of soma-space workshops we have reached at through the planning process, theory-infused by Winther’s (2014) embodied professional competence concept and further developed through the design team’s bodily, collaborative, and arts-based planning sessions.

Karen Barad’s agential realism

The philosophical understandings we read and analyse this article with grow out of Barad’s (2007) agential realism. Agential realism is an onto-epistemological positioning, where knowing/being, body/mind, science/art, and theory/practice, as well as ethical perspectives, are viewed as non-separable, always, and constituently on the move and entangled (Maapalo & Østern, 2018). This is described by Barad (2007, p. 185) as the study of practices of knowing in being, a point of view where humans are seen as always part of, and intra-acting with, other human and non-human bodies, nature and structures (Østern & Dahl, 2019). Barad (2007) uses the concept intra-acting instead of interacting, indicating that things are not separate parts in the first place, and then connecting, but from the beginning are entangled. Entanglement is then a concept that points towards this connectedness. In this article, material-discursive entanglement is used as a central theoretical concept in the analysis. Material-discursive entanglement indicates that materiality (things) is not superior to discourse (words), but that they equally intra-act (Juelskjær, 2019). Based in Barad’s thinking, Lenz Taguchi (2010, p. 3) introduces an intra-active pedagogy for the kindergarten field in which she emphasises intra-active relationships with all living organisms and the environment. This appeals to us as researchers/educators/artists and connects with our bodily and spatial ways of knowing. Only when we analyse research material, through what Barad (2007) calls diffraction through cutting-together-apart, do we pull moments in the flow of planning out in focus (cutting together) to look at them in an otherwise ongoing, complex flow of phenomena. As we read the agential cut with theory, we cut it apart and create new insights of the cut through thinking-with-theory (cutting apart). It is important to notice that agential realism is not about de-humanising, just de-centring the human centrality for meaning-making, so that also non-human materiality is understood as agentic for knowledge production.

Material-discursive entanglement, agential cutting and intra-action, we as authors and researchers, as well as Winther’s (2014) theory/practice, are central aspects that together make up the complex knowledge apparatus for this article. A knowledge apparatus (Barad, 2007) is the theory-practical understandings we read and think with in this article. Through this knowledge apparatus, we cut-together-apart as we create, articulate, and discuss workshop design and design principles in this bodily planning study.

Analysis layer 1: Design principles for the entanglement of early pedagogy and somatic dance

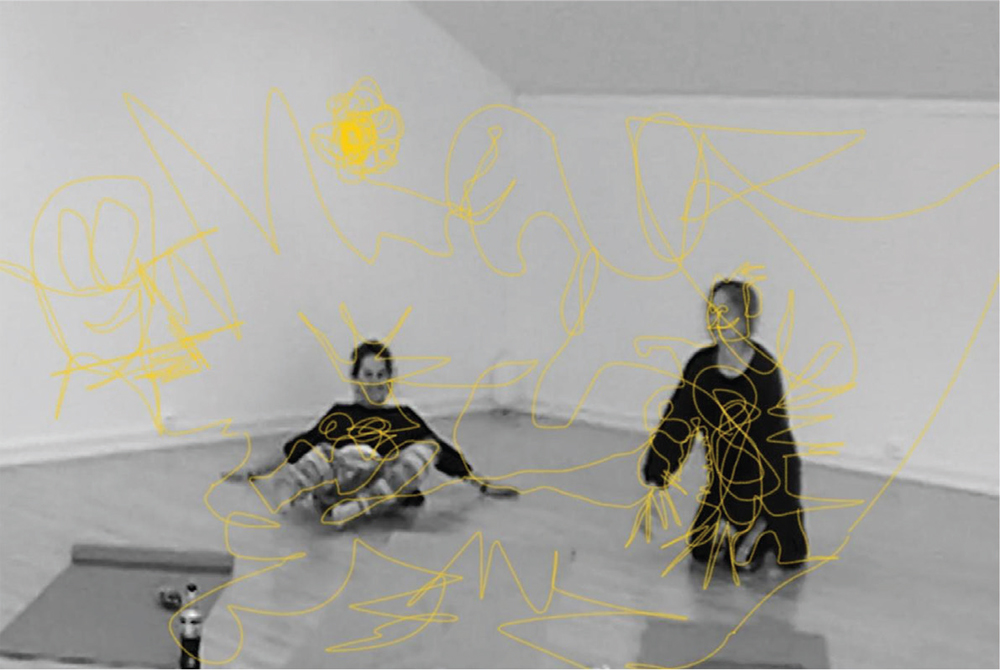

There are some aspects the design team have noticed during and after the planning sessions: these “somethings” are moments of change that have made a difference and have taken the planning further. These moments are presented in stories, or bodily narratives, and process-images from the planning-sessions (figure 2–5). Arts education researcher Leavy (2018) describes these as hunches, a way of listening to your internal monitor (p. 11). The hunches can be compared to what Lynn Fels, coming from the field of drama and theatre research, calls stop moments (Fels, 2012). Fels explains a stop moment as a moment when something special draws attention or as “the interruption, the tug on the sleeve, that stops me” (Fels, 2012, p. 51).These hunches, or stop moments, again, can be understood as moments where agential cuts can be made, using Barad’s vocabulary as analytical approach. Through an agential cutting together/apart (Barad, 2007) of moments that we experience as hunches (Leavy, 2018), or stop moments (Fels, 2012), we create four entanglements in intra-action with the research material and discuss how they are connected and can work as design principles when designing workshops aiming at developing kindergarten teachers’ bodily professional knowledge. Further, we show how kindergarten pedagogy and somatic dance pedagogy are intra-acting in the entanglements.

The following four felt-sensed entanglements, which will be unpacked in the remaining parts of the article, we cut-together-apart as especially valuable during the planning sessions, and as of specific value for the emerging workshop design:

to body – to space

to listen – to respond

to rest – to move

to play – to create

These four entanglements further became the design principles for the workshops that this study of the planning sessions resulted in. A design principle is a prompt for actual practical action, in this case for how bodily professional knowledge can be developed through workshops for kindergarten teachers.

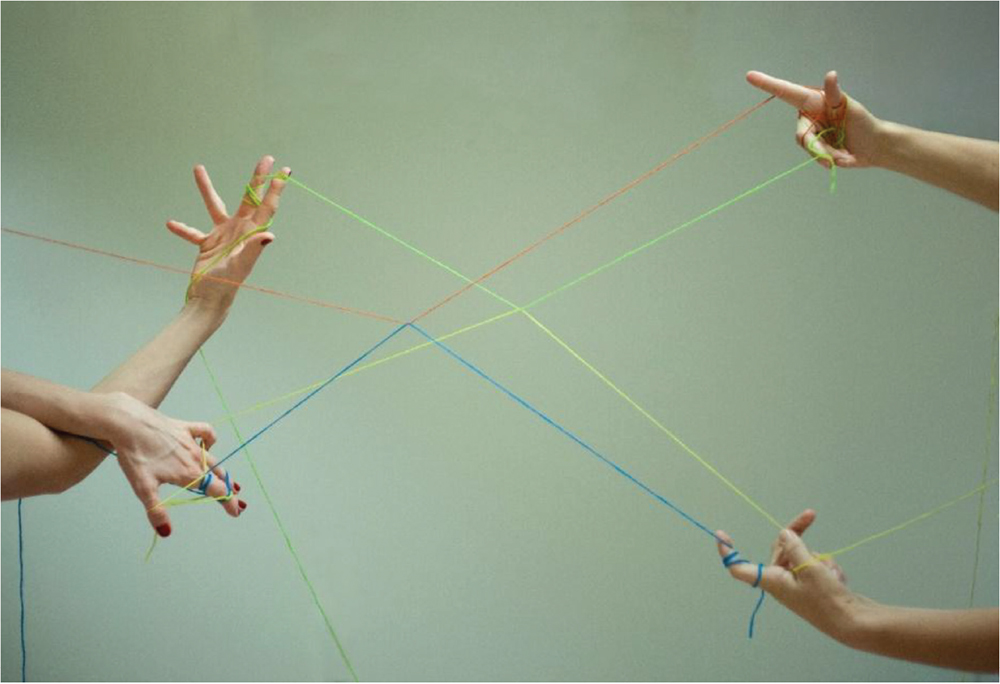

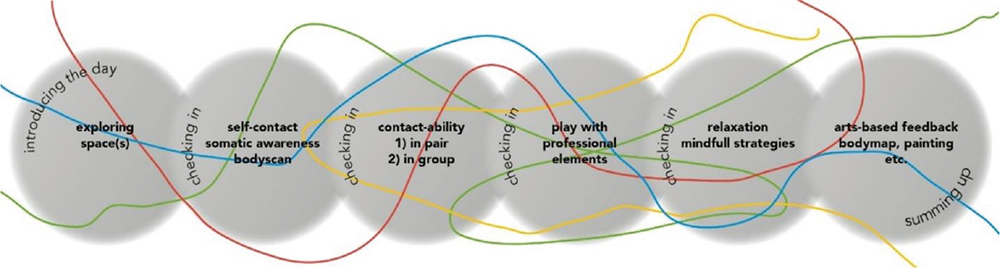

The four threads (Figure 1) that we created together as part of the analysis, showing our hands holding the wool threads, are a visualisation of the four entanglements; one coloured tread for each entanglement. With the four threads we seek to show how the four entanglements are mixed and, at the same time, lifted out for analysis. In the following we open the four entanglements, that we understand as design principles for the workshops with the kindergarten teachers. The entanglements are presented through process-images from the planning sessions (Figure 2–5), where we have drawn the different entanglements as lines/treads in blue, orange, green and yellow upon the process-images in Figure 2,3,4 and 5. Further, the four entanglements are blended into the workshop design shown in Figure 6, running as design principle threads through the workshop design.

The analysis further consists of narratives from our lived experience while bodily planning, based on our logs and video-transcript from the planning sessions. The narratives (stories) are examples of bodily discoveries during the planning sessions and are placed under the process-images from the different entanglements. Under the process-image and the narrative, we then entangle early pedagogy and somatic dance through thinking-with Winther’s theory/practice, Barad’s (2007) material-discursive entanglements and other previous research. In the following, we cut-together-apart (Barad, 2007) each of the four entanglements under four different subtitles.

Entanglement 1: To body – to space

We feel like children exploring a space, feeling the back leaning towards the hard wall, a cheek meeting the cold wooden floor and the wind from the other running past. It is as if the space tells us what it has to offer to our process. We are on the floor, walking, spinning, talking, touching, writing, drawing, and moving in time and space. Feeling what this space can give us and how it can enable bodily meaning-making for us today. (Bodily narrative based on log from bodily planning session)

The first analytical entanglement, which we, as a design team, experienced as a hunch in our planning process, we express as to body – to space. Tone Pernille Østern (2015) has experimented with creating a verb out of the noun body. Through this, it would be possible to talk about the body in a dynamic way, as we can with thinking through the verb “to think”. Østern (2015) asks: What if we can say “Yesterday I bodied the world in such and such a way, but today I body it in a quite different way” (p. 4). Ida again has brought the verb into the kindergarten teacher profession (Pedersen, 2019) as a tool for writing and talking about kindergarten teachers’ bodily professional knowledge. While playing with the new noun in this context, we articulated to space as the entangled twin of to body. This verbing of nouns, as they materially and discursively entangle (Barad, 2007), gives us the opportunity to understand, talk and write about embodiment and learning in new and dynamic ways.

When we body the planning sessions, valuable information is opened and added to the process in a felt-sensed way, and the way we space together is expanding the bodily knowing in the process. This also gives us felt-sensed information about what the space can offer and thereby also gives us the opportunity to get to know, invite in, and empower the space as central in the soma-space workshops for developing professional knowledge.

Several early childhood research/literature/practices examine how the kindergarten classroom can be created and used in a way that makes space for creativity, activity, and relational work between children and children–adults. One example is the principle of the environment as third teacher, which comes from the Reggio Emilia pedagogy in the region of Emilia in northern Italy. Loris Malaguzzi, the founder (1996; Wexler, 2004), has had a great influence on the field of early pedagogy. Malaguzzi advocates a holistic approach to the education of young children. By stating that children hold hundred languages, he positions the arts and the senses as central for learning/teaching. Further, Lenz Taguchi (2010, p. 58) points out that learning is not separable from practice, and development of professional knowledge does not just happen inside the kindergarten teacher but manifests itself in the entanglement between kindergarten spaces and their human and non-human bodies/agents. Learning is produced in the meeting between bodies, materials, and discourse as they intra-act. The entanglement to body – to space underlines this.

The decision to have the planning sessions in a dance/yoga space was made because we wanted to have the opportunity to be on the floor and move around in that space together whilst planning. This is influenced by our background from dance and somatic practice. This opens the opportunity to merge body and space together with a hyphen to show how they entangle. By sensing how our bodies and the space melt together we feel a hunch to articulate this as a design principle for future workshops for the kindergarten teachers. The bodily work in the planning sessions made us aware of the body-space entanglement as an unexplored field/part in previous research about kindergarten teachers’ professional development.

To body – to space invites us to re-think the value of bodies and spaces in professional development for kindergarten teachers. It is like awakening the embodied nature of pedagogy (Dixon & Senior, 2011, p. 483), asking how do we body and how do we space in professional development in education and practice. The entanglement to body – to space insists this question is worthwhile to re-body/think.

Entanglement 2: To listen – to respond

Looking at the video again, we get the bodily-listening-feeling, a feeling difficult to explain with words on paper. Our bodies are carefully listening to each other, not only with our ears, not talking this time, not just looking, but connecting through all the senses. It is as if our bodies are saying “I can feel what you’re trying to say, I support you by following and answering with giving my weight to you, and at the same time sensing whether this is something for you, and what your response is.” There’s a fine line between questioning and answering, suggesting, and expecting, listening, and responding. We are entangled. (Bodily narrative based on video transcript from a bodily planning session)

The second entanglement that we created through a hunch (Leavy, 2018) in our planning process was to listen – to respond. We understand a bodily-listening-feeling as if the whole body is tuning in to the other (Dixon & Senior, 2011; Østern, 2013; Winther, 2014), listening with arms, legs, and torso, feeling how the other is moving fast or slowly, gently or hard, and connecting through breathing when lying side by side. This is in line with somatic dance education (Rouhiainen, 2008), and connects with the Reggio Emilia philosophy, where the listening, known as the pedagogy of listening, here means to deeply engage in the world and therefore highlights the significance of giving time and space to make this kind of listening possible (Åberg & Lenz Taguchi, 2006; Wexler, 2004). This is understood as “sensitivity to the patterns that connect,” and an openness to the world (Rinaldi, 2006, p. 65). We recognised such connecting patterning in our bodily exploration of ideas for the workshop. This connecting patterning is intimately tied to emotions “generated by curiosity, desire, doubt and uncertainty,” and can be understood as a process “that does not produce answers but formulates questions” (Rinaldi, 2006, p. 65). Listening is here understood as a metaphor for being open and sensitive to listening, and being listened to, not just with our ears, but through all our senses (Rinaldi, 2006). Bodily and spatial listening feels crucial for us to sense and experience what the soma-space workshop could be like.

Looking to the research field of somatic dance and movement, Østern (2013) explored how the practical-pedagogical knowledge of two contemporary dance teachers was embodied through the teachers’ bodily listening, bodily tutoring, and bodily ambiguity, which can be understood as what Jaana Parviainen (1998) describes as kinaesthetic empathy at play in bodily professional knowledge. Charlotte Svendler Nilsen (2014) indicates that this means sensing the other person’s kinaesthetic experience, but at the same time being aware that you do not fully understand what the other person is feeling (p. 114). Bodily listening and kinaesthetic empathy from somatic dance and movement, as presented above, thereby resonates with and expands the pedagogy of listening (Rinaldi, 2006) by including a holistic body-subject. In the same way, we responsively felt-sensed into each other during the bodily planning phase and recognised this as an important entanglement and design principle to bring into the workshops with the kindergarten teachers. In this wave of listening and responding we tuned into one another like dancers in improvisation, like how kindergarten teachers and children may meet and relate within the kindergarten spaces.

While listening to each other and the space, we discovered the opportunity this offers for kindergarten teachers to get to know themselves, each other and how the body is body-talking and relating to kindergarten children, spaces, and material within the kindergarten. Entangling somatic dance and early pedagogy gives an opportunity to expand the concepts in the entanglement: listen – respond. To listen and to respond thereby grows to listening and responding with the whole body, to human and non-human agents in material-discursive practices and awareness about how the pedagogical space(s) restrains or opens for bodily professional knowledge development.

Entanglement 3: To rest – to move

Today’s planning session feels like a wave of movement and rest. We alternate between walking around, exploring the space, moving together, talking and writing, often laughing, but also silent still and silently moving. Listening to each other without words. Carefully listening to the body when feeling the need to move, but also allowing rest to be an important part of the ongoing planning process. It is like breathing the process, an inward gaze and outside awoke awareness. (Bodily narrative based on log from bodily planning session)

The third analytical entanglement in our bodily planning process is experienced as to rest – to move. It is as if the bodily planning process has a pulse, which we cannot overlook. We experience it like breathing the process. This responds to somatic dance education (Buono, 2019; Rouhiainen, 2008), which highlights mindful and somatic practices, where breathing and connecting are understood as important in education. In somatic dance and movement practises this balance of moving, stopping and sensing is of great importance. Through resting and paying attention to small movements, stopping, sensing again, and noticing yourself, your somatic awareness, getting to know yourself, the space, and the other(s), is being developed.

Alexia Buono (2019) introduces a mindful somatic pedagogy that brings mindfulness and somatics into kindergarten contexts through embodied research. By doing yoga with children in kindergarten, she investigates how children mindfully notice the choices they make, notice what happens around them and self-regulate (Buono, 2019, p. 157). Buono (2019) further accentuates the importance for early childhood educators to feel safe going inwards, and to outwardly express their sensations to provide a pedagogical learning environment where the children feel safe in knowing themselves. The children’s need for rest is well known in early pedagogy practise, as the children (0–3 years old) often rest or sleep during the kindergarten day (Ulla, 2017), but there has been less focus on the teachers’ needs regarding this.

This is, however, not an attempt to say that kindergarten teachers can solve their conceivable tiredness only through mindful strategies. But by feeling and acknowledging this need for rest, we, in the design team, can find a way towards cutting-together-apart and discuss rest, and at the same time acknowledge that rest is material-discursive entangled with the kindergarten practice it intra-acts with. Rossholt (2012) points out that the body becomes extra noticeable when it expresses too much or too little compared to what the material-discursive practice expects, like noise or silence. The expectations are not always given, but in constant negotiation and becoming (Rossholt, 2012, p. 15), entangled with the material-discursive practices they are situated in, much like the constant (often unspoken) negotiation of rest and/or move in kindergarten space(s). To carefully listen to each other without words while planning made us acknowledge the entanglement to rest – to move as an important part of bodily professional knowledge development within the kindergarten profession.

Giving rest value in the professional practice and development of the kindergarten professional knowledge, and playing with the entanglement, the entanglement and design principle to rest – to move, invites the body to listen more accurately to the need for rest and balance also in educational settings. We suggest that acceptance of (guided) rest might be a valuable part of kindergarten teachers’ bodily professional knowledge development, as it might give something to the educational practice, and nurture the space for/with the children as well.

Entanglement 4: To play – to create

While lying on the floor, both of us laughing, a good feeling spreads through our bodies. Laughter fills the room in a good way, opening our faces in smiles. Our bodies are warm and relaxed, bringing a caring feeling and bringing us closer to one another. We are playing together and thereby we dare taking the risk to jump into uncertainty, to create something new. (Bodily narrative from log from bodily planning session)

The fourth analytical entanglement and becoming design principle in our planning process we express as to play – to create. Play has a crucial role in early pedagogy (Løkken, 2000; Nome, 2017; Øksnes, 2010), but still the focus has been mostly on the children’s play. Throughout this project we as a design team realised the importance of embodied play in these planning sessions, and also how playing in the actual workshops, with the kindergarten teachers, could be a way of working with the kindergarten teachers’ professional and embodied play competence in kindergarten, and at the same time open for creating new understandings. Dag Øystein Nome (2017) describes play as a way of being together, in a conglomerate of bodies in movement, spaces, things, words, and other sounds (p. 171). In this entanglement we thereby experience how playing together while planning opens for acknowledging play as an important aspect of professional development. According to Maria Øksnes (2010), it is central in play that the ones who are playing surrender and fall into the play universe. Getting involved in the play means that we are not standing on the outside or raise ourselves above it, but rather get pulled into it (Øksnes, 2010, p. 189). This also resulted in exercises in the workshop where the participants could, for example, bring a toy from everyday practice and play with it, or when we planned to crawl around in the kindergarten classroom to explore the space in a bodily and playful way. As Øksnes (2010, p. 185, based on Gadamer, 2007) points out, it is no longer we who play the play, but the play that plays us. How playing relates to creating thereby became clear to us throughout the planning sessions, as the dance was dancing us.

Play is a language that kindergarten teachers are well acquainted with, but it seems rather forgotten in educational settings, courses, and conferences within professional development for kindergarten teachers. This entanglement is about having a playful attitude, removing resistance towards play felt in the teacher body, and giving play the status that it lacks. Opening for play in professional development may also open for creating new knowledge about our own practice. To play – to create, as an entanglement and design principle, thereby opens for letting loose, taking the language of play seriously, and with that open for creative and arts-based approaches to professional development for kindergarten teachers.

Summing up, we suggest these four entanglements to body – to space, to listen – to respond, to rest – to move and to play – to create as workshop design principles, guiding principles, or creative impulses, offering pedagogical possibilities to explore and understand embodied dimensions of teaching/learning to teach (Forgasz & McDonough, 2017, p. 52) as we open for kindergarten teachers to body kindergarten spaces in new ways. Next, we take these design principles with us and move towards the creation of a workshop design for our soma-space dance workshops.

Analysis layer 2: The design of soma-space dance workshops

In the following, we introduce the workshop design that we, the design team, created together through the bodily planning process, and which was later carried out with the kindergarten teachers. Our workshop design is theory-infused by Winther’s (2014) embodied professional competence concept. We remind how Winther (2014) emphasises embodied professional competence as three aspects: (1) self-contact and somatic awareness, (2) communication reading and contact ability, and (3) leadership in groups and situations. We have used these aspects as perspectives when going into the bodily planning sessions. As a result of our collaboration, we add space, that comes from the entanglement to body – to space, play and arts-based feedback, from the entanglement to play – to create, and relaxation from the entanglement to rest – to move, as additional dimensions to Winther’s theory/practical framework, when researching how bodily professional knowledge can be developed for kindergarten teachers.

The workshop design we created follows a trajectory starting with (1) exploring space, which is planned as a starting point for each workshop to establish the room as a frame or a base for movement. This is a way to get to know the space, make it familiar and safe to move around in, and at the same time open up for knowing the space(s) in new ways, as we did in the planning sessions. Next, we turn into focus on (2) self-contact through somatic awareness, which is drawn out of Winther’s (2014) theory/practice, a way of focusing on contact to the self, using different mindful techniques like bodyscan, while lying on the floor or sitting in a chair. (3) Contact-ability indicates workshop tasks focusing on human and non-human agents working in pair and groups, trying to move in contact with others, feeling nearness and listening into the other(s) through movement. In this part we planned different contact exercises, where the participants could move together and connect to each other, as well as with the space and its objects. (4) Play with professional elements is a component that arose while playing around in the planning sessions. The exercises grew out of our bodily collaboration and from our experiences from different educational and somatic practice situations. In one of the workshops, we planned for asking the kindergarten teachers to bring an object they use in their everyday practice (a toy, spoon, towel, bucket or spade, for example). The plan was to explore our intra-action with this “thing” through the bodily senses. Then, (5) relaxation, where we planned for using mindful techniques as a way to find rest. This component connects with the entanglement to rest – to move that flows through the workshop design visualized as one of the lines/treads in different colours (Figure 6). The trajectory ends with (6) arts-based feedback (bodymapping3/painting/performing), which implies using arts-based expressions when giving feedback from the day, a way to lift and give value to other ways of responding then just verbal. This relates to Malaguzzi’s (1996) focus on using more of the hundred languages, as we argue this to be important for grown-ups as well, and a way to develop professional knowledge for kindergarten teachers.

In-between the different parts in the workshops we find space for feedback and discussions on how the different tasks feel and if/how they connect with the kindergarten teachers personal/professional (Winther, 2014) practice: we call this checking in. When moving in the workshop-trajectory, the entanglements to body – to space, to listen – to respond, to rest – to move, and to play – to create, as design principles, flow through (Figure 6) and entangle with the workshop design.

Through the bodily planning sessions, the content has emerged with different open somatic dance and movement exercises that we, as the design team, present in the actual workshops (Pape-Pedersen, 2022), and that we all explore together as we delve into what bodily professional knowledge is and how it can be developed. We planned different exercises that opened for the teacher-bodies to find their own way of moving, guided by us. We created a plan, a workshop design, but at the same time we open up for creating together with the participants as the workshops develop, keeping in body-mind that the workshop design is just a trajectory to improvise around.

We have now presented the workshop design for our soma-space workshops made for developing kindergarten teachers’ bodily professional knowledge and will now conclude through discussing how the four entanglements and the workshop design work together as entangled bodily workshop design that can be used as a starting point for workshops aimed at developing kindergarten teachers’ bodily professional knowledge.

Entangled bodily workshop design

As a result of this bodily, collaborative, and arts-based workshop design study, we have shaped and articulated a workshop design for the soma-space workshops, and created the four entanglements to body – to space, to listen – to respond, to rest – to move, and to play – to create as design principles, guiding principles, or creative impulses, which we invite kindergarten teachers and teacher educators, as well as somatic dance teachers, to play with in order to develop bodily professional knowledge. The entanglements might also work in other educational settings, with children in kindergarten, school pupils, or students in higher education. Inviting educators in different fields to ask: How do we body and how do we consider space with its materials in educational sessions? How are we opening for listening and responding more extensively and bodily for all involved? How do we plan for and sense the need for rest and movement, and how are play and time to create permitted and opened for when teaching?

In this study, we have focused especially on the planning stage of a professional development project. For us, it was necessary to go through a bodily planning process, not only a thought planning process to create a series of workshops that felt legitimate and that would offer deep and transformative learning opportunities towards bodily professional knowledge. The feeling of getting deeper into the planning increased as concepts, body and art entangled with the space that we were in and the materials we were intra-acting with. A key point in this article is therefore how the decision-making process, when planning, is highly embodied, emotional, and spatial. As a result, we suggest that through the bodily, collaborative and arts-based planning process between a kindergarten educator and a somatic dance teacher, the value of bodily planning is to really sense what is at stake, and to invite the body into the decision-making process.

Based in our insights, knowing the highly embodied practice that the kindergarten teachers find themselves in, we find it strange and troublesome that a cognitive and “bodyless” discourse still dominates learning and teaching within kindergarten education, professional development and planning in educational settings (Larsson & Fagrell, 2010). Through the intra-action of early pedagogy and somatic dance, in this study we have opened the kindergarten spaces for new ways of teacher-bodying. Doing the planning in a kindergarten space, might have been interesting, as that would have offered another, more “messy” space than the empty dance/yoga space we were in while planning. However, a kindergarten space was not available for us during this planning process. Through cross-fertilising education, arts, and bodily-material relations as potentials for professional development, we aim at entangling early childhood pedagogy and somatic dance education towards a bodily approach to professional development in kindergarten teacher education. The workshop design created in collaboration between a kindergarten teacher and a somatic dance teacher can be seen as an entangled bodily design, consisting of four entanglements and a workshop-trajectory, created to develop kindergarten teachers’ bodily professional knowledge.

References

- Åberg, A., & Lenz Taguchi, H. (2006). Lyttende pedagogikk – etikk og demokrati i pedagogisk arbeid [The pedagogy of listening. Ethics and democracy in pedagogical work]. Universitetsforlaget.

- Barad, K. (2007). Meeting the universe halfway: Quantum physics and the entanglement of matter and meaning. Duke University Press.

- Buono, A. (2019) Interweaving a mindfully somatic pedagogy into an early childhood classroom. Pedagogies: An International Journal, 14(2), 150–168, https://www.doi.org/10.1080/1554480X.2019.1597723

- Dixon, M., & Senior, K. (2011). Appearing pedagogy: From embodied learning and teaching to embodied pedagogy. Pedagogy, Culture & Society, 19(3), 473–484, http://www.tandfonline.com/doi/full/10.1080/14681366.2011.632514

- Coole, D., & Frost, S. (Eds.). (2010). New materialisms: Ontology, agency, and politics. Duke University Press

- Fels, L. (2012). Collecting data through performative inquiry: A tug on the sleeve. Youth Theatre Journal, 26(1), 50–60

- Forgasz, R., & McDonough, S. (2017). “Struck by the way our bodies conveyed so much:” A collaborative self-study of our developing understanding of embodied pedagogies. Studying Teacher Education, 13(1), 52–67.

- Gadamer, H.-G. (2007). Sandhed og metode [Truth and method]. Academica København.

- Haseman, B. (2006). A manifesto for performative research. Media International Australia Incorporating Culture and Policy: Quarterly Journal of Media Research and Resources, 118(1), 98–106.

- Jackson, A. Y., & Mazzei, L. A. (2012). Thinking with theory in qualitative research. Viewing data across multiple perspectives. Routledge.

- Juelskjær, M. (2019). At tænke med agential realisme [Thinking with agential realism]. Nyt fra samfundsvitenskaberne.

- Larsson, H., & Fagrell, B. (2010). Föreställningar om kroppen. Kropp och kroppslighet i pedagogisk praktik och teori [Viewpoints on the body. Body and embodiment in pedagogical practice and theory]. Liber.

- Leavy, P. (2018). Introduction to arts-based research. In P. Leavy (Ed.), Handbook of arts-based research (pp. 3–21). The Guilford Press.

- Lenz Taguchi, H. (2010). Going beyond the theory/practice divide in early childhood education. Introducing an intra-active pedagogy. Routledge.

- Løkken, G. (2000). Toddler peer culture: The social style of one and two year old bodysubjects in everyday interaction [Doctoral dissertation]. University of Agder.

- Maapalo, A. P., & Østern, T. P. (2018). The agency of wood: Multisensory interviews with art and crafts teachers in a post-humanistic and new-materialistic perspective. Education Inquiry, 9(4), 1–17.

- Malaguzzi, L. (1996). History, ideas, and basic philosophy. In C. Edwards, L. Gandini & G. Forman (Eds), The hundred languages of the childhood (pp. 41–89). Ablex Publishing Corp.

- Malchiodi, C. A. (2018). Creative arts therapies and arts-based research. In P. Leavy (Ed.), Handbook of arts-based research (pp. 68–87). The Guilford Press.

- Massumi, B. (1995). The autonomy of affect. Cultural Critique, 113(31), 83–109.

- Nome, D. Ø. (2017). De yngste barnas nonverbale sosiale handlingsrepertoar – slik det utvikler seg og kommer til uttrykk i norske barnehager [The youngest children’s nonverbal social repertoire as it unfolds and apars in Norwegian kindergartens]. [Doctoral dissertation]. University of Agder.

- Øksnes, M. (2010). Lekens flertydighet. Om barns lek i en institusjonalisert barndom [The ambiguity of play. Children’s play in an institutionalised childhood]. Cappelen Akademisk.

- Østern, T. P. (2013). The embodied teaching moment: The embodied character of the dance teacher’s practicalpedagogical knowledge investigated in dialogue with two contemporary dance teachers. Nordic Journal of Dance, 4(1), 28–47.

- Østern, T. P. (2015). To body. In S. Schonmann (Ed.), International yearbook for research in arts education. At the crossroads of arts and cultural education: Queries meet assumption (pp. 144–149). Waxmann.

- Østern, T. P., & Dahl, T. (2019). Performativ forskning – sentrale teoretiske og analytiske begreper i boka [Performative research – central theoretical and analytical concepts in the book]. In T. P. Østern, T. Dahl, A. Strømme, J. Aagaard Petersen, A.-L. Østern & S. Selander (Eds.), Dybde//læring – en flerfaglig, relasjonell og skapende tilnærming [Deep education – a cross-curricular, relational and artful approach] (pp. 29–37). Universitetsforlaget.

- Østern, T. P., Jusslin, S., Nødtvedt Knudsen, K., Maapalo, P., & Bjørkøy, I. (2021). A performative paradigm for post-qualitative inquiry. Qualitative Research, 1–19.

- Pape-Pedersen, I. (2022). Teacherbody(ing) kindergarten space(s). An arts-based pedagogical development project for kindergarten teachers. European Early Childhood Education Research Journal, 1–15. http://doi.org/10.1080/1350293X.2021.2011366

- Parviainen, J. (1998). Bodies moving and moved [Doctoral dissertation]. Tampere University.

- Pedersen, I. (2019). Med embodied pedagogy og småbarnspedagogikk på paletten. Å se nyanser av rødgul farge i to (u)like fag og forskningsfelt [With embodied pedagogy and kindergarten pedagogy on the palette. Nuances of red and yellow colour in two (un)similar research fields]. På Spissen Forskning/Dance Articulated, Special Issue Bodily Learning, 5(3), 25–44. http://dx.doi.org/10.18862/ps.2019.503.2

- Pedersen, I., & Orset, A. K. (2020). Stunder av ingenting, der alt kan skje – en innkjenning av og samtale om kroppslig profesjonskunnskap i barnehagen [Moments of nothing where everything can happen. Talking of and feeling into professional knowledge in kindergarten]. Tidsskrift for professionsstudier, 16(31), 52–61.

- Rinaldi, C. (2006). In dialogue with Reggio Emilia: Listening, researching, learning. Routledge.

- Rouhiainen, L. (2008). Somatic dance as a means of cultivating ethically embodied subjects. Research in Dance Education, 9(3), 241–256.

- Reinertsen, A. (2016). Hva er det med Irma? På veg mot immanente kritikk praksiser og rettferdige utdanningsøyeblikk [What is it with Irma? On the move towards immanent critique practise(s) and justice in educational movements]. Tidsskrift for Nordisk Barnehageforskning, 12(6), 1–12.

- Rossholt, N. (2012). Kroppens tilblivelse i tid og rom. Analyser av materielle-diskursive hendelser i barnehagen [Body-becoming in time and space. A material-discursive analyses of doings in kindergarten]. [Doctoral dissertation]. NTNU Norwegian University of Science and Technology.

- Sandvik, N. (2016). Småbarnspedagogikkens komplekse komposisjoner i et sammenvevd og uoversiktlig psykologisk, pedagogisk, politisk og økonomisk felt. [The complex compositions of Early pedagogy in an interwoven field of psychology, pedagogy, politics and economy]. In N. Sandvik, N. Johannesen, A. S. Larsen, M. R. Nyhus & B. Ulla. Småbarnspedagogikkens komplekse komposisjoner. Læring møter filosofi [The complex compositions of early pedagogy. Learning meets philosophy], (pp. 9–33). Fagbokforlaget.

- Savid-Baden, M., & Howell Major, C. (2013). Qualitative research. The essential guide to theory and practice. Routledge.

- Sheets-Johnstone, M. (2009). The Corporeal turn. An interdisciplinary reader. Imprint Academic.

- Skovhus, M., & Winther, H. (2019). Udvikling af pædagogstuderendes lederskab gennem krop og bevægelse [Developing student teachers’ leadership through body and movement]. idrottsforum.org, 1–16.

- Song, Y. & Yun, E. (2017). Lessons from somatic literacy for early childhood physical education. International Journal of Early Childhood Education, 23(2), 97–122

- Svendler Nielsen, C. (2014). Krop, kinæstetisk empati og pædagogisk tone i undervisningsprosesser – skitse til en fænomenologisk didaktik [Body, kinaesthetic empathy and pedagogical tone in educational processes- drawing a phenomenological educational design]. In H. Winter (Ed.), Kroppens sprog i professional praksis. Om kontakt, nærvær, lederskab og personlig kommunikation [The language of the body in professional practice. Contact, nearness, leadership and personal communication] (pp. 111–119). Billesø & Balzer.

- Ulla, B. (2015). Arrangement av kropp, kraft og kunnskap: Ein studie av profesjonsutøvinga til barnehagelæraren [Arrangement of body, power and knowledge: A study of kindergarten teachers professional practice]. [Doctoral dissertation]. University of Oslo.

- Ulla, B. (2017). Reconceptualising sleep: Relational principles inside and outside the pram. Contemporary Issues in Early Childhood, 18(4), 400–408. https://doi.org/10.1177/1463949117742781

- Wexler, A. (2004). A theory for living: Walking with Reggio Emilia. Art Education, 57(6), 13–19.

- Winther, H. (2008). Body contact and body language: moments of personal development and social and cultural learning processes in movement psychology and education. Forum Qualitative Sozialforschung, 9(2), 1–23.

- Winther, H. (2009). Bevægelsespsykologi- kroppens sprog og bevægelses psykologi med utgangspunkt i danseterapiformen Dansergia [Movement psychology- the language of the body and movement psychology based in the dance therapy form Dansergia]. [Doctoral dissertation]. Copenhagen University.

- Winther, H. (2014) Det professionspersonlige – om kroppen som klangbund i professionel kommunikation [The professional-personal – about body as sounding board in professional communication]. In H. Winther (Ed.), Kroppens sprog i professionel praksis – om kontakt, nærvær, lederskab og personlig kommunikation [The language of the body in professional practice. Contact, nearness, leadership and personal communication] (pp. 74–88). Billesø & Baltzer.

- Winther, H., Grøntved, S. N., Graversen, E. K., & Ilkjær, I. (2015). The dancing nurses and the language of the body: Training somatic awareness, bodily communication, and embodied professional competence in nurse education. Journal of Holistic Nursing, 33(3), 182–192.

Footnotes

- 1 The bodily turn (Sheets-Johnstone, 2009) points towards an increased awareness of the meaning of the body in education, research and language.

- 2 The material turn (Coole & Frost, 2010; Lenz Taguchi, 2010) gives materiality agency, decentring the human subject as the main agent for meaning-making, acknowledging things, spaces, nature and the agentic capacities of all other non-human organisms.

- 3 Body-mind maps is used in art-therapy inquiry (Malchiodi, 2018, p. 83) and is also used in kindergarten as a way for the children to get to know their body and body-parts.