Our article is a developing and collective investigation of experiences in Nordic art education that considers homogeneity and the need for pluralism in this institutional framework. We explore the dilemmas inherent in the implementation and practice of inclusion, as recommended in policy documents from an inter-Nordic educational system, the Nordic Community School of Music and Arts1 (NCSMA) (Arts Council Norway, 2019; Norsk kulturskoleråd, 2016, 2019; Kulturskolenettverket, 2019; SOU 2016: 69). NCSMA is publicly funded and organises voluntary schools for children and young adults throughout the Nordic area. The NCSMA’s policy documents suggest the need to actively attract and recruit participants from a diverse society, which contrasts with the recruitment needs of obligatory educational structures. We agree that the recruitment of a pluralistic student body should be prioritised and seek understanding of how this is addressed in the art educational sector.

During this study, we struggled through blind spots in our knowledge to understand how other perspectives are received. We explore conflicting individual positions in Nordic art educational systems, in the colonial matrix of power (CMP)2 (Quijano, 2007). The three members of our emerging collective, Gry, Helen and Zahra, embody distinctive educational and geographical starting points and varying, shifting positions in the colonial matrix of power and its constructed racial hierarchy. All three authors are educators in visual art education. Gry is unmarked3 racialised White, born, raised and living in Norway, and is also an artist and a doctoral candidate in these fields. Helen is unmarked racialised White, British with a Norwegian parent; she was brought up in the UK and moved to Norway in 1990. She is an artist and a doctoral candidate. Zahra’s point of departure is perceived as part of the dominant Iranian majority. In a Scandinavian context, she is marked racialised as non-White; she fled to Sweden with a young child because of war and political oppression. Zahra holds a doctorate in educational systems and supervises doctoral candidates in visual art practices; she is the doctoral supervisor for Gry and Helen. All three authors have children often seen as Other due to their physical appearance: hair, eyes, skin colour. These different starting positions enable us to challenge the colonial matrix of power as it emerges, for example, when we were collectively working on the images.

The key agency in this article is the image. Its reception through our collective dialogical method is central to its final manifestation (cf. Vázquez, 2020). The porosity of our individual positions allowed the tacit, implicit knowledge in the image to reorientate our respective positions to otherwise colonial, stabilised phenomena (Eriksen et al., 2020). We tried to resist locking ourselves in our first reactions or thoughts; we tried to give each other time to change direction and allow ourselves to challenge each other’s non-fixed positions which were apt to shift when confronted. Thereby, we began to understand our reactions as the emergence of a position that we momentarily inhabit.

Our analysis developed when we, the authors, met alone and in gatherings with other groups of academics, decision-makers and teachers in the field of Nordic art education. We were concerned about how the practice of inclusion meets recommendations in policy documents in the NCSMA. We found ourselves entangled in events and situations that demanded something of us as humans; they called for a response-ability to act ethically (Eriksen et al., 2020). Our research question became: What can prevent pluralistic cultural knowledge production in the NCSMA? More questions emerged as we pursued the research question: Who is absent in art educational knowledge production spaces? How is that absence maintained?

This study-as-assemblage is a deliberate performance of the kind of epistemic disobedience argued by decolonial scholar Walter Mignolo (2011, p. 45). It is an experimental attempt to contribute to the development of a more organic presentation of thought processes and creative forms of expression.4 In the following text, we move away from a conventional linear academic format to accommodate the complexities and multi-dimensionality of our collective and individual thinking processes. We alternate between positioning our subjectivity as we and as I (in the form of our various author agencies). The text, written from a we-position, is disrupted by interventions written from individual perspectives.

The initial intervention is placed as the beginning of our journey: Gry participates in a homogenous White gathering consisting of researchers, teachers and decision-makers aimed at inclusion in art education. Then the unified voice of “we” re-turns: centring the NCSMA’s historical and present social mission as we draw on post-colonial, theoretical perspectives and decolonising practices. Then we describe our diffractive method. Zahra intervenes: she shares her experience of offering her critical perspective to a group of teachers, researchers and decision-makers. Helen responds: she shares her experience and positions herself in a majority perspective to suggest the invisible work of Whiteness in the conflicting forms of silence and verbal aggression. Finally, we close in on specific entanglements in knowledge production and discuss the call to respond.

Gry: Who can Speak? Who must listen?

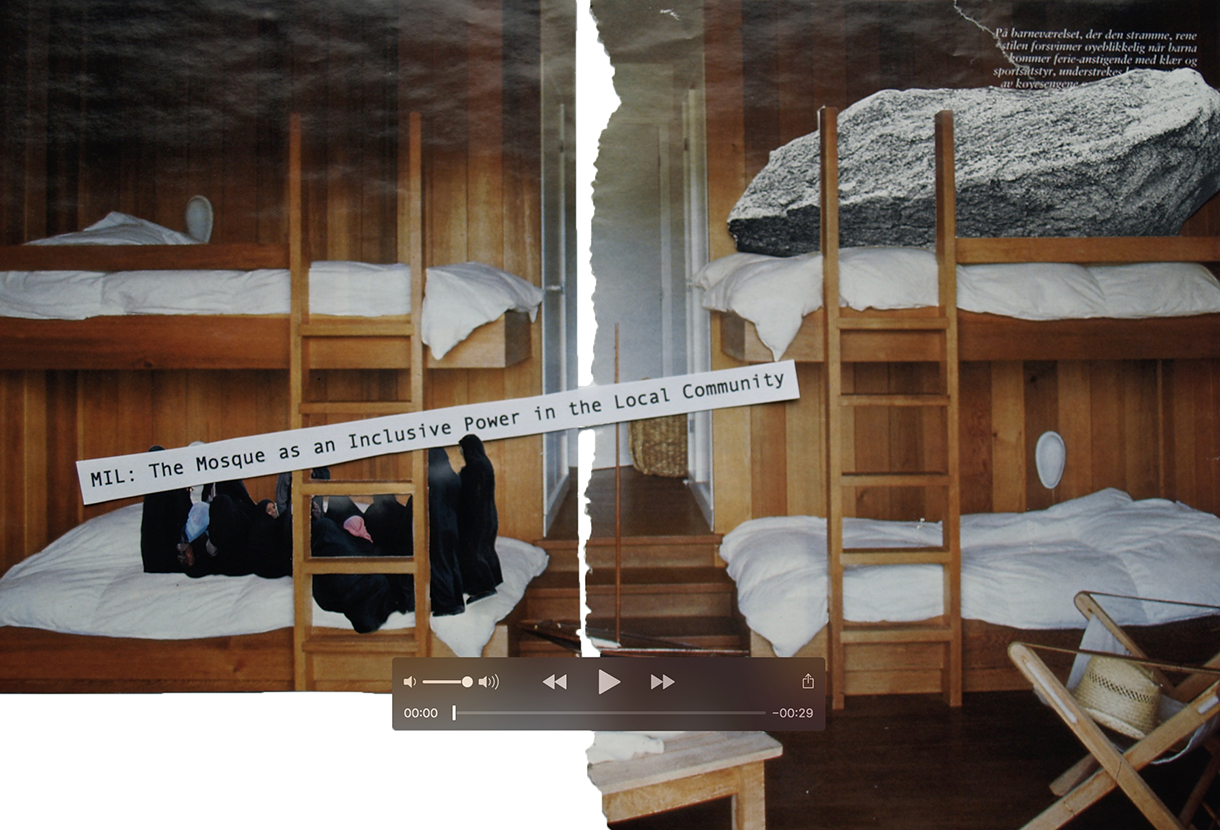

I came home from another all-White gathering in the Scandinavian art educational field focusing on inclusion, feeling troubled and confused. I made an animation of pictures and sound (Fig. 1) responding to the questions arising in me:

Who is present in the discussion about inclusion in art educational settings?

How are invitations to participate in these discussions distributed?

Whose knowledge is desirable?

Which questions are permissible?

Who is allowed to interpret and judge the definition of relevant knowledge in this context?

I was trying to draw attention towards mechanisms and discourses about inclusion in art education by flipping the lens. The words I put in the mouths of Others made the power gap much more apparent to me. The discussion in the animation (Fig. 1) between fictive female members of a Muslim congregation is about the possibility of persuading members of the secular majority to join them. How will the secular majority benefit? And what name could be used to describe this group of people? In the animation, the vibrating rock in the upper bunk is pointing towards the force of self-satisfied White privilege, a metaphor of the complacent and self-sufficient work of inclusion that will neither relinquish positions nor privilege to the people they wish to include.

My thinking resonates with Ninos Josef (2019), Swedish-based artist and educator: “If the cultural cycle is imbued with a colonial view of what is accepted as cultural capital from its very beginning, we have planted the seed for an exclusionary Nordic cultural sector” (Josef, 2019, p. 3). They argue that marked racialised children in the Nordic countries do not have equal rights, opportunities and access to participate in the cultural cycle, the NCSMA being the first stop in this exclusionary cycle.

I believe there is a need to focus on cultural production to be enacted locally, in the everyday institutional lives, on everyday decision-making with their situational dilemmas and challenges (cf. Alemanji, 2019; Haugsevje et al., 2016). The political and cultural debate must go beyond concluding that cultural policy is not working for inclusivity, diversity, and participation based primarily on statistical macro-data (Haugsevje et al., 2016, p. 82). I was immersed in a dominantly White art-educational gathering that demanded another way of thinking about plural representation, so I asked for structural action to be taken.

The managerial response was to invite artist-researchers as Critical Friends (CF)5. CF’s mandate holds an advisory function in networks, gatherings and seminars that lacks representation (Arts Council Norway, 2019). Invitations to CFs is a strategy to perform inclusion at an institutional level used by the Nordic culture field in general and the art education field specifically. Marginalised or minoritised individuals or groups defined as Other (cf. Said, 2000) are invited to give their reflections on their needs related to the centre of knowledge construction.

NCSMA: Mission and reality

The history of the NCSMA is overwhelmingly dominated by a White western majority producing Eurocentric knowledge. From a socio-economic class perspective, the rise of the NCSMA in the mid-20th century had a compensatory mission to address the lack of access to culture and contributed to cultural production: to fill a gap between the different socio-economic classes (Berge et al., 2019; Jakku-Sihvonen & Kuusela, 2002). However, the contemporary flow of migration from the global South has resulted in demographic changes; in the Nordic region, class background is no longer the most central indicator of social position. Social position and its economic fundament have been racialised. Racialised people are excluded from upward social and economic mobility as their expertise is undervalued; most visibly in being overqualified for the job market in which they are included. Economic incomes are thus reduced (Bayati, 2016; Josef, 2020). This challenges the idea of what is possible and normative for cultural production in the Nordic region. Thus, the NCSMA needs to reconsider its original and established task of aspiring to socio-economic equality through conventional policies and strategies by reassessing the ways that pluralist knowledge productions are included or excluded, ignored and silenced.

Publicly available curricula and strategic documents published for use in and by the NCSMA express an aim to attract a more diverse student body to represent all groups in contemporary society. Recent enquiries show that extracurricular music education in Finland functions as a closed or autopoietic social system (Väkevä et al., 2017). In Norway, the NCSMA is “characterised by static organisation” unavailable to all children and is thus “Norway’s best-kept secret” (Berge et al. 2019 p. 186–187, our translation). Furthermore, frequent and continued launching of inclusivity and diversity projects in national as well as Nordic programmes suggests that inclusivity is difficult to accomplish. The Nordic national states’ ministerial and art educational institutional policy documents specifically articulate the idea that cultural expression is indicative of freedom (democracy) and transformation (development). A strategic document from the NCSMA states:

Art and culture create arenas for belonging, community and participation that are a prerequisite for Nordic democracy […] NCSMA shall be an accessible place in the lives of children and young people, for art and cultural experiences, for personal, social and artistic growth and development, regardless of gender, social class, ethnicity, orientation, economy and origin […] NCSMA must be a carrier of continuity and tradition, but also be at the forefront of art and cultural development and relevant in the society from which it springs. (Norsk kulturskoleråd, 2020, p. 3)

However, there is a tendency towards arts advocacy rather than critical thinking in art education. Rubén Gaztambide-Fernández, Amelia Kraehe and Stephen Carpenter (2018) claim that the emphasis has rather been how the arts can challenge racism and encourage social justice than looking at how racism and White supremacy define and constitute the field. The tendency to advocate rather than to think critically about its field of knowledge production can be attributed to the often fragile status of the art institutions:

The arts in education has been late to reckon with its racist past and white supremacist present. This is in part because the scholarship of the arts in education has been largely about arts advocacy, and as such there has been a general reluctance among arts educators and researchers to recognize, theorize, and address the ways in which the arts operate in relation to and are implicated in white supremacy. (Gaztambide- Fernández et al., 2018, p. 2)

We consider it imperative to challenge any “well-meaning” policy based on ineffective advocacy of the arts.

Knowledge production, entanglements and the call to response

We met with specific entanglements in the NCSMA that we analyse through our understandings from the transdisciplinary fields of post-colonial, critical race and Whiteness theories and processes of decoloniality. Post-colonial theories relying on understandings of the western practice of Othering (Said, 2000) and the silencing of the subaltern (Spivak, 1988) provide a framework in this study to explore the absence of the discursive Other in the NCSMA. Furthermore, contemporary research and cultural production are entangled in the colonial matrix of power (CMP) that controls all aspects of human life through mechanisms of global economies, politics and knowledge production, as well as aesthetics through the senses and perception (Mignolo & Vázquez, 2013).

This entanglement can be contextualised by understanding the limitations of the Cartesian logic of modernity (Feyerabend, 2010) with its dualistic preferences that prioritise expansion and technological innovation and create a binary split between the environment and human life forms and the development of the separated subject (Barad, 2007; Ferreira Da Silva, 2007). The ongoing Enlightenment discourse of emancipation is based on changes within the existing system and unquestioning about the logics of coloniality that emerging nation-states were enacting. Modern aesthetics founded on Enlightenment logic conserves a normative canon to disregard and reject other forms of artist practice as being proper and true art forms (Kester, 2011, Mignolo & Vázquez, 2013; Gaztambide-Fernández et al., 2018; Vázquez, 2020).

Critical race and Whiteness theories understand Whiteness as a racialising category that dominates all categorisation through unarticulated White privilege (McIntosh, 1988). When White fragility (DiAngelo, 2011) manifests in racial conflict, it is seen in “the outward display of emotions such as anger, fear and guilt and behaviours such as argumentation, silence, and leaving the stress-inducing situation” (p. 54). White innocence (Wekker, 2016) explores the social paradox of denial of racial discrimination and historical colonial violence. Both innocence and fragility are structures that could unwittingly support an oppressive colonial structure, that is, White supremacy, despite the good intentions of the subject. White supremacy as articulated here is hidden, non-articulated and commonsensical for the dominant group and thoroughly epistemologically, ontologically and culturally embedded (Bayati, 2014; Mills, 2015; Wekker 2016).

The concepts of Whiteness and White supremacy and their implications for Nordic societies can be understood through another concept: Nordic exceptionalism (Hansen et al., 2015; Schierup & Ålund, 2011). Nordic exceptionalism is the notion of self and the understanding of the Other in Nordic countries. It perpetuates the idea of neutrality, peace, equity and social equality with satisfied nations and citizens who believe they have for example a generous asylum policy. The public welfare system is assumed to be the perfect role model at the forefront of antiracism, feminism and the environmental movement (Hansen et al., 2015; Lundström & Hübinette, 2020; Schierup & Ålund, 2011). Contextualising this chapter with Nordic exceptionalism will allow the reader to notice a gap between good intentions and the failing implementation of inclusionary NCSMA policy. In our specific art and academic contexts, our challenge to Nordic exceptionalism is inspired by indigenous political scientist Rauna Kuokkanen’s concept of homework (2010). She refers to Derrida’s argument that if theory is to be grounded in the practice of everyday life, any intervention in the process of decolonisation has to be more than theoretical but performed in social and material relationality with bodies of resistance (Lugones, 2010). Rather than doing fieldwork outside, we are working to make our home, that is, the art education system, a pluralistic place of work with a more hospitable environment for everyone to work and thrive in.

Tracing diffractive methodology

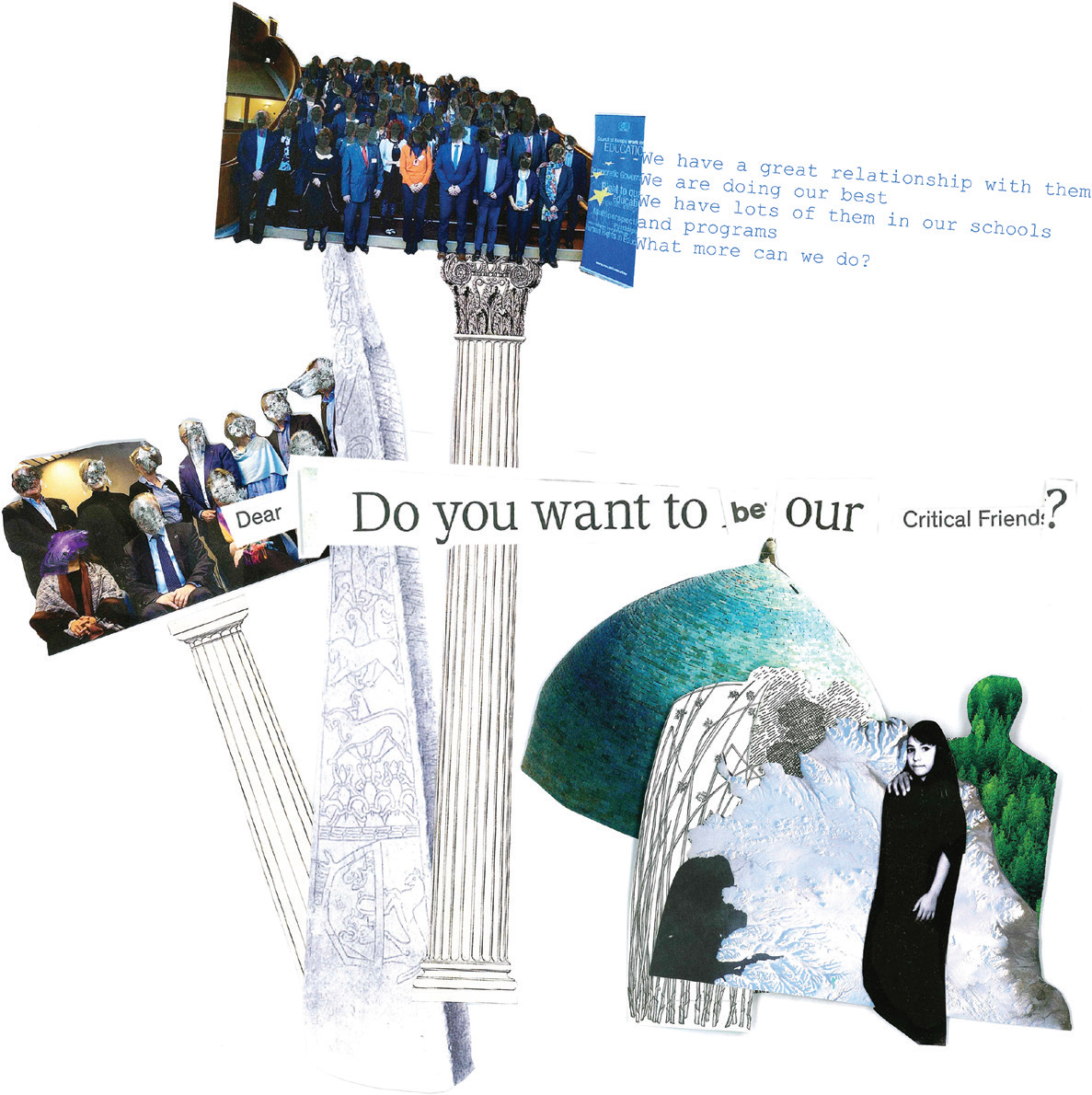

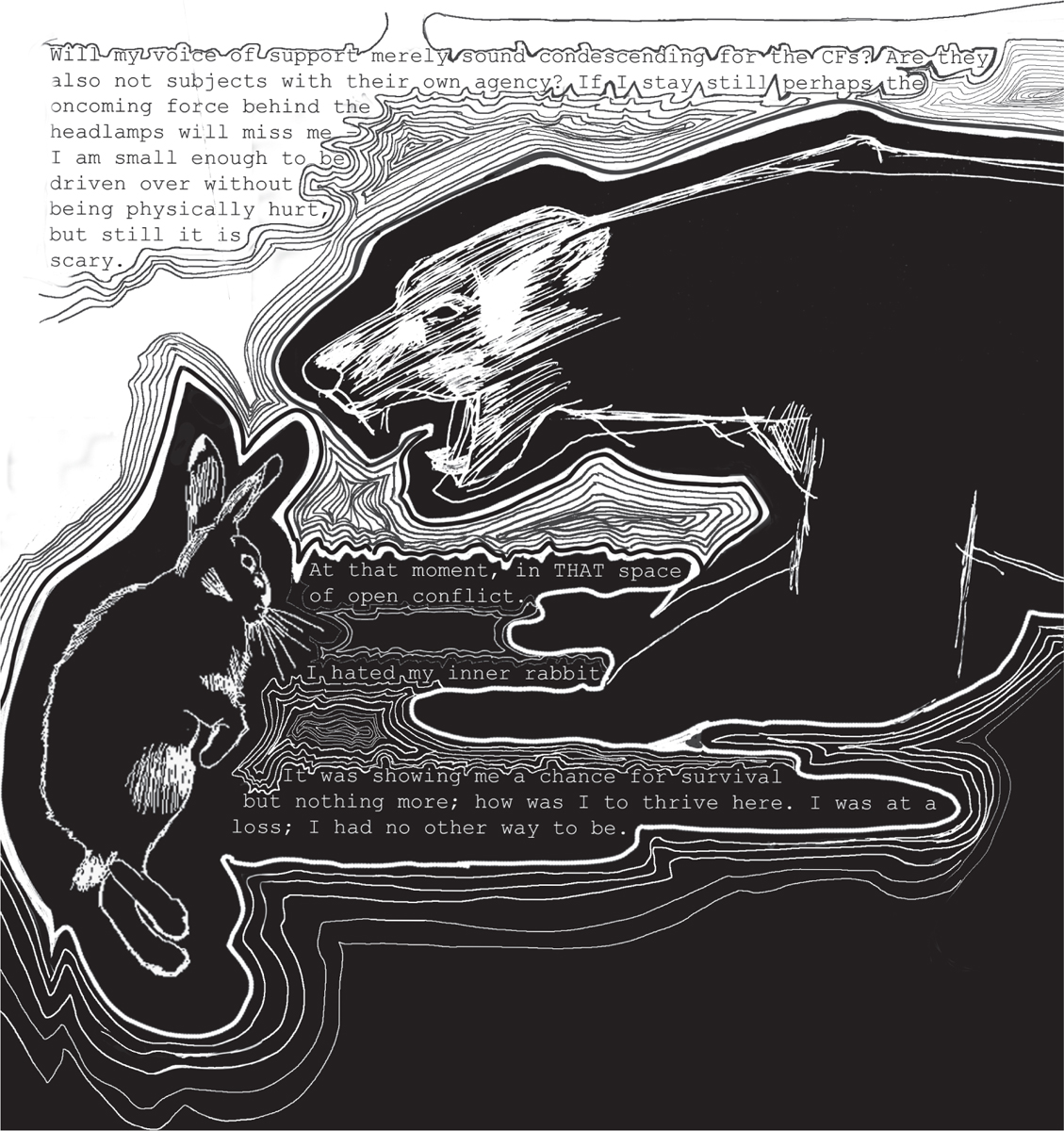

The starting points for our collective are the experiences of being a CF (Zahra) and being participants in a gathering where CFs were invited (Gry and Helen). We are three co-researcher-subjects as we became our own research subjects. Over the course of 24 months, we held two-hourly weekly meetings predominately in virtual spaces. Our empirical material emerged as we diffracted theoretically and embodied understandings. Our sources were individual note-/logbooks, memory work, social media chats and e-mail correspondence between us, drawings, animation and collages, literature, the socio-historical context and the study of policy documents, colleagues’ input on our work, experiences in conferences presenting this inquiry and our own autobiographical stories. We also delved into official reports and communicated, challenged and provoked each other in our internal discussions. For example, Gry used collage, text, and animation with sound as an entry into the complexity of decolonisation (Fig. 1 and 2). Helen draws colonising phenomena in the form of a rabbit and a polar bear (Fig. 3) developed during the inquiry. In our analysis, “thinking and feeling cannot be understood as separated but entangled” (Lenz Taguchi & Palmer, 2013, p. 676). All authors have contributed to the composition of the images through dialogue and comments exemplified in Figure 2 and the following comment.

Zahra’s rendering of Gry’s collage in Figure 2:

My interpretation is that the right side of the image represents the good intentions of the project that I described earlier; it is about White subjectivity. The left side of the image shows how good intentions make themselves a subject and the Other an object. At the same time as you have made the picture of me as a child visible, you have erased my family and turned them into somewhat ghostly figures.6 How about moving and putting them onto the heads with the White gaze at the top of the pillars where they are ghosts in the colonial mind anyway. My family are real and exist! You must show more clearly that the ghostly figures are the White gaze’s projection of their own colonial and racist historical narrative. The White gaze is cut off from the child’s reality because there is a pre-existing colonial stereotype of those children and their parents and their relationships.

The epistemological concerns produced in this text are founded on the concept of diffraction (Barad, 2007, 2014). This concept allows a way of understanding the complexity of decolonising processes in our study. Diffraction allows new patterns to emerge if we understand our positions as entangled in many differing phenomena beyond linear cause-and-effect scenarios. We experience research as having a performative agency of its own. Through it, we explore our entanglement as research subjects within the academic discourses: art education, decoloniality, and antiracism. We observe that we move in a porous, nomadic manner between qualitative and post-qualitative inquiry,7 searching the outskirts of methodology to understand different perspectives, experiences, and conflicts in our collective. A diffractive analysis allows us to inquire into “encounters of multiple material- discursive agents and situated practices, and what emerges as differences in these events” (Lenz Taguchi & Palmer, 2013, p. 672).

Furthermore, we incorporate the materiality of art production when generating analysis, as well as when disseminating results. In dialogue and analysis between us, we produced several visual works articulating our own effect and embodied experiences. In the intra-action during image co-construction, we come to understand the entanglements and reciprocal response-ability of the maker and receiver of the image (see Fig. 2 and 3). Our images unpack artistic methods starting from individual artistic actions and are developed through peer discussion, transferring them to a transdisciplinary expression. This enables us to unpack our lived and racialised experiences.

Zahra: Safe space for whose unsafe idea?

In my position as a senior lecturer, I have been invited to speak at countless seminars, conferences, student unions and staff gatherings and, on occasion, as CF, as well as an inspirational speaker to talk about my research and PhD thesis entitled The Other in teacher education – A study of the racialized Swedish student’s conditions in the era of globalization (Bayati, 2014).

This time, another researcher and I had been invited as CFs to present our perspectives on inclusion and diversity in Nordic art education and to participate in following discussions in smaller groups. The moderator reminded everyone that the gathering was defined as a safe space for unsafe ideas.8 We both talked mostly about the problem of exclusion, colonial and stereotypical images, Eurocentric content that affected the education system and cultural scene in the Nordic countries. We were discussing how representation matters in education, knowledge production and cultural life in an era of globalisation. My presentation was based on my own research, and I presented the empirical results from my PhD study that shows how students from non-European backgrounds were challenged by and struggled with exclusion and other obstacles in three Swedish universities. In this instance, and in a dedicated safe space, our presentations as CFs were harshly criticised with similar accusations from decision-makers or researchers from the dominant majority of our respective countries. We were denounced in various ways: of ingratitude, of being naughty and rude, and dirtying them individually with properties that they did not recognise in themselves; accused of speaking nonsense and relying on anecdotal references.

When we split up for group work, a researcher I was not acquainted with accused me of shameful behaviour and throwing muck on them. No one else in the group of teachers and or decision-makers commented on this at all; they just exchanged glances; I was so shocked that I could only say that what I had said was not directed at anyone personally and was, in fact, the results of my study. I also wondered why if everything was as positive as people were indicating why these types of gatherings were being organised to create inclusive and diversity in art education? Afterwards, I kept my mouth shut. I was still shocked by such a direct and personal attack; it reminded me of what bell hooks says:

Often this speech about the Other annihilates, erases. No need to hear your voice when I can talk about you better than you can speak about yourself. No need to hear your voice. Only tell me about your pain. I want to know your story. And then I will tell it back to you in a new way. Tell back to you in such a way that it has become mine, my own. Re-writing you, I write myself anew. I am still author, authority (hooks, 1990, p. 151–152)

In the light of the bell hooks quotation, it is interesting to observe the surprise of Helen and Gry when they held presentations of our research without me. They observed that they met little resistance and were in a bubble of consensus with an audience that was almost only White Scandinavian. This is very interesting as it is the opposite of the reactions provoked by the same material when I was with them. Their point was that my body caused the difference in reactions towards the same materials when I was absent or present. It suggests how entangled my physical presence is to the reception of our research. Do they meet little resistance when I am not there because they have a privileged background? Are they more included despite having the same critical approach as me? Do Nordic White people understand the insight of Gry and Helen as generous, tolerant and open-minded as a reflection of themselves?

Helen: Deafening silence

My way into this chapter is through the event that Zahra has just described, as it awoke an understanding in me. It was embodied and can be described as leaving a feeling of unease that started a process of questioning.

I was at a gathering of teachers, researchers and decision-makers in art education when things got heated. Here, I find myself in the same position as always in aggressive atmospheres. I stayed silent – it was extremely uncomfortable for me to sit and listen to these CFs being bombarded with resistance through accusations of unfairness and suggestions of partisanship and over-sensitivity. Perhaps the idea that “neutral” scientific institutions could be considered colonial and racist triggered this outrage? Perhaps the representatives of these institutions felt confronted and incompetent? Perhaps the arrow had pierced their own skin, and they felt hurt?

A CF had just delivered a speech about the state of Swedish academia based on her research as an educational researcher positioned as the Other in academia. A researcher confronted the CF by reinforcing the suggestion that their institution was doing its utmost to recruit and keep the Other.

The finger of blame at ethnic imbalance in the Swedish university system was not pointed to the institution and its structures, but it was laid at the feet of the physically obvious Other. The CF calmly suggested that it was the framework of the system that sabotaged integration, and it held the power of definition about utmost in this context.

Another CF also had their experience refuted by a decision-maker. The criticism of the recruitment of children from minority backgrounds was not only challenged but refuted and disregarded as acceptable. They too were doing their utmost, and doing well, because they have minority pupils in their schools.

This was a meeting of affect. It was embodied in two non-White bodies challenging the system of producing Othering in education systems and art scenes in Nordic countries. In this meeting, witness statements were challenged and rebutted. Whiteness with its privilege and power rejected any form of criticism and thus closed the window of dialogue.

Here, emotions ran high; the room was triggered, engaged – here was an agency at work provoking reactions to the presence of CFs in a room of privileged Whiteness. If I took their place, I would feel highly vulnerable in this situation. What happened to this human aspect of the Other position in a safe space and unsafe ideas? I have never encountered such fierceness when I deliver an opinion in public. Since then, I have experienced that the discussion of integration strategies, despite inherent tensions, is always civil when Gry and I present our work. This has not often been the case when Zahra is present in the presentation: criticism of our perspectives can often be harsh and belittling.

One of my colleagues was agitated enough by the verbal conflict and the response of collective silence – they refused to be still and take part in the act of silencing the much-needed debate – they said that they were “tired” of White people in managerial positions refusing to acknowledge their part in a system that racialised people and their experience of the world. I saw another way to be in this situation. I ached to be that person that could articulate their position.

I left the space with a question that has taken me on a rewarding, but painful path of understanding and growth.

“What if … I was that White researcher?”

As usual, I weighed it up with another question:

“Why not?”

Presumption for structural pluralism and decolonisation

The departure point for this chapter is Gry’s unease at the lack of pluralism in a gathering about inclusion, in an art educational institution. It was a matter that caused general concern at this meeting. The prevailing assumption was a lack of competency in the art and education field in marginalised groups. In the Norwegian context, musicologist Sunniva Hovde (2021), drawing on Sætre et al., suggests that the lack of data on teacher background in primary and secondary education must be addressed as learners are found to place importance on the ethnic and cultural backgrounds of their teachers in learning processes. Hovde further argues that it becomes increasingly significant that student teachers explore cultural experiences outside of their own contexts. Hovde also draws attention to teaching being nominally influenced by structural policy documents. This supports our primary assumption of a discrepancy between well-meaning intentions / policy documents aiming at inclusion, and the enactment of critical antiracism in art education.

During our analysis we encountered entanglements that showed how and why racism emerges invisibly at an organisational level in art education. Helen and Gry emerged with a deep-rooted, undetectable ontological bias that White researchers and educators perform with research colleagues from non-Western backgrounds (cf. Smith, 2013). This coloniality of knowledge production is embedded in the Enlightenment’s ontological framework, with cultural and political anchoring and psychological mechanisms that enable racial inequality within education in general. For example, the Swedish school curriculum (Skolverket, 2019) describes current values: “In accordance with the ethics borne by a Christian tradition and Western humanism, this is achieved by fostering in the individual a sense of justice, generosity, tolerance and responsibility. Teaching in school must be non-denominational.” The implications of our exploration relate not only to different levels in the field of art education but to a wider discussion of the ontological frameworks in western academia. Recurring questions kept appearing in our discussions:

Whose knowledge do we recognise as curriculum?

Whose knowledge do we dismiss as identity politics or anecdotes?

Who is gatekeeping the definitions of valid universal knowledge?

What are the desired values of Western humanism?

Response-abilities

We were entangled in complex situations/events that demanded a response. We could not predict how any of these events would develop. If we could have foreseen them, we would have surely avoided some of them. Therefore, part of our study becomes a “flashback” to situations/events that we experienced as we became increasingly sensitised to what was happening when we were presenting our work in progress. We ask ourselves what are the response-abilities of the researcher in situations entangled with the phenomena of Othering, exclusion and racism. Our definition of response-ability is more than a response to the situation, but also an answer from a position of answer-ability: “ethics are not just a problem of knowledge but a call to a relationship” (Spivak et al., 1996, p. 5). Furthermore, our response disrupts existing margins to include the opening of a new discursive space for each other. In order to decentralise Eurocentric academic thinking and look at knowledge production as more than a transaction between the academic and art educational institutions, we would like to deepen the understanding of the relationship between institution and individual beyond the transactional.

We have opted to be transparent about our own starting points whilst anonymising other people and places. We do not identify specific individuals but focus on structures that support some groups of individuals whilst excluding other marginalised or minoritised groups (Eriksen et al., 2020).

Deafening silence, aggression and resilience

We recall art educational gatherings in which we participated, and racial conflicts to which we responded through our collective research practice. Here we saw the racial conflicts from the educational gatherings echoed. However, in the context of the gatherings, the conflict was amplified. The perspectives of the CFs evoked well-known bullying techniques of aggression and silence (cf. DiAngelo, 2011; Bayati, 2014; Matias, 2016; Wekker, 2012).

These manifestations of Whiteness intra-act with the demand of the Other to expand the margins by categorising and expelling challenges to dominating knowledge as irrelevant or uncouth (cf. Motturi, 2007; Said, 2000). The frightened rabbit modus, as in Figure 3, can be seen as a metaphor for White fragility and innocence that limits White emotional engagement in a knowledge conflict. However, the silence that is produced is an enabler for pacified colonial mindsets (cf. DiAngelo, 2021; Matias, 2016; Spivak, 1988; Wekker, 2012). It is only during the intervention of the protesting White colleague that the desire to act otherwise is ignited in Helen. Here, the intervention in local structural processes not only challenges entrenched structures, but also negotiates and shifts individual positions within the CMP.

The resistance met by CFs should also be contextualised within the CMP as it coincides with a hardened political and public debate apparent in social media and the daily press. These responses include: the problem lies with the marginalised or minoritised group or person exposing and criticising social inequalities, excluding these critical voices from public conversations. Another symptom of a hardened public debate is the ready dismissal and exclusion of researchers with a critical perspective that challenges power structures from both academic and artistic perspectives, especially during processes of knowledge production. Critical perspectives are fiercely attacked when the person addressing these problems is a part of a marginalised or minoritised community (Ahmed, 2012) rather than when a member of the majority tells the same story as the earlier bell hooks quote points out. Examples from the National Academy of the Arts (KHiO) turbulence around decolonising the curriculum (Kallelid & Pettrém, 2020; Kifle, 2020), and academic artist interventions (Skovmøller & Danbolt, 2020), and fear of loss of academic freedom (Brekke & Heldal, 2020; Vartdal, 2019) show a polarisation. Critical post-structural thought and conventional knowledge production are apparently under threat when the premise for knowledge production within arts and education is questioned.

The re-turn

Re-turning to our research question: What can prevent pluralistic cultural knowledge production in the Nordic Community School of Music and Arts? During this process, we encountered clear parallels between our own need to include and be included and the articulated desire of the NCSMA to be an inclusive social power (Norsk kulturskoleråd, 2019). The organisational structure of the NCSMA is entangled with privileged White individuals in positions of power.

Our exploration was diffracted through multiple perspectives, and the total research experience encounters prevailing racialised inequalities. We tried to immerse ourselves in racial sensitising and the realisation of situations through intra-action in a context where the inclusion of marginalised youth was the main focus for teachers, decision-makers and researchers in art education. We experienced structural as well as psychological phenomena that restricted the emergence of pluralist knowledge. As researcher-subjects, our ongoing analysis re-turned us continually to a specific entanglement that obstructed pluralism and the inclusion of marginalised groups; that is, the continuing construction of Nordic Whiteness that is affected by and affects research communities, teachers and decision-makers in the cultural and educational sectors. This powerful Eurocentric phenomenon allows the hierarchy of White supremacy to keep the racialised CFs and other minoritised individuals in its organisational margins.

This study acknowledges the tensions that can arise when White positionality is paired with decolonising practices. Whiteness when considered a product of coloniality will always reflect the racialized conflicts of colonialism. However, we have needed to name our positions in the CMP in order to centre the process of racial destabilisation encountered. Through our collective work, race emerged as a point of emotional vulnerability. If the concept of race is to be understood as unstable, flexible and thus porous (cf. Garvey & Ignatiev, 1993; Painter, 2011), the very phenomenon can be open to a collective transformative process. We show that our co-research processes were dependent on the presence of researchers placed in different positions in the CMP. Through physical proximity, we came closer to an understanding of both marked and unmarked racialised identities as unstable.

We show this in our continual dialogue, for example, when Zahra articulates her reception of Figure 2 and when Helen wishes to transform into the vocalising White researcher. The intention is not only to shift position but to transform into another state of being; a state of being that can allow room for these learning processes. It is promising that the NCSMA articulates inclusion in its policy documents with the best of intentions; it does, after all, suggest a willingness to change. However, when the NCSMA is embedded in the culture of Nordic exceptionalism, as indicated in this article, good intentions become an impervious membrane of resistance to Other perspectives. The organisation becomes difficult to penetrate for non-Eurocentric thinkers and doers; its perspective of knowledge production is resolute and difficult to challenge.

It is time to direct the question towards larger structures. We ask ourselves, why do organisations and individuals experience pain when human inadequacy is challenged in the context of art education? The answer could lie in Spivak’s understanding of a Eurocentric move of innocence; it is a “right” not to know or understand the constructs of racialising structures (Spivak, 1994, p. 25). How do we activate the processes needed to breathe life into ineffective, but well-meaning, policies in a manner acceptable to everyone? Representation of minoritised groups in dominant White and racialised hierarchies is an important step in achieving the proximity that we found necessary to include Other perspectives. However, it is far from adequate without its companion concept of individual and organisational porosity. The NCSMA facilitates the access of power to produce knowledge; the question is how this privilege of access is facilitated to all its potential students. All organisations, community institutions or groups and individuals need to consider their actions in the shadow of Eurocentric colonial structures and epistemologies. We claim that, through the NCSMA’s related research on integration, there is an accumulation of privilege taken up by centre dwellers, benefiting from the centre’s power and a continuation of constructing the contours of the margins (cf. Spivak, 1988). Space must be created for plural forms of art and Other knowledge so that they can contribute to a pluralistic and cosmopolitan knowledge production with many centres (Kuokkanen, 2010; Motturi, 2007).

Yet, it appears that the desire to be inclusive, that is good intentions, is in fact the foundation for a shift in racial understanding on a personal level. However, as this study shows, those good intentions have to be anchored in a willingness to enter into undefined, muddy areas that are painful to reconcile with the idea of the benign White racial self-understanding. These are subtle and ongoing processes that individuals encounter. We experienced that these processes can only happen if pluralist perspectives are allowed to develop through proximity and a willingness to engage with and actualise good intentions. Otherwise, we repeat Whiteness, which on a systemic level, creates systems that are inflexible and non-permeable, and that conserve a White European knowledge system. Thus, it seems that the way in which to be more inclusive is through proximity to individuals with different knowledges than prevailing systems. On an organisational level this means beings fully acknowledged and respected members of groups aiming for plurality.

This effort of practising decolonisation in an art organisation means accepting and rising to the challenges faced by dominating organisational and knowledge production practices, rather than dismissing them.

We re-turn to the question raised by Gry: “Who can speak? Who must listen?” Challenges must be heard in their entirety, with the full contextual and historical implications for the positions in which we are entangled in the CMP. As Zahra later confronts Gry about Figure 2:

“you have made the picture of me as a child visible, you have erased my family and turned them into somewhat ghostly figures […] they are ghosts in the colonial mind anyway. My family are real and exist!”

We take a pause in our research and a final question asks of us: Is it at all possible for the teachers, administrators and researchers, in art education generally and the NCSMA specifically, to practice antiracism and decoloniality as inclusionary strategies and thus meet the needs of their own teaching mandates and student-teacher curriculums?

We re-turn to Helen’s flippant comment: “Why not?”

Bibliography

- Ahmed, S. (2012). On being included racism and diversity in institutional life. Duke University Press.

- Alemanji, A. A. (Ed.). (2018). Antiracism education in and out of schools. Palgrave Macmillan.

- Arts Council Norway. (2019, October 1). An inclusive cultural sector in the Nordics. Kulturrådet. https://www.kulturradet.no/inkludering/vis/-/aktivitetar-og-initiativ-i-inkluderande-kulturliv-i-norden-prosjektet

- Arts Council Norway. (2019, October 1). KIL-Manifesto. Kulturrådet. https://issuu.com/norsk_kulturrad/docs/kil_kulturskolemanifest

- Barad, K. (2007). Meeting the universe halfway. Quantum physics and the entanglement of matter and meaning. Duke University Press.

- Barad, K. (2014). Diffracting diffraction: Cutting together-apart. Parallax, 20(2), 168–187. https://doi.org/10.1080/13534645.2014.927623

- Bayati, Z. (2014). The Other in teacher education – A study of the racialized Swedish student’s conditions in the era of globalization. [Doctoral dissertation, University of Gothenburg]. http://hdl.handle.net/2077/35328

- Bayati, Z. (2016). Koloniala diskurser och rasifieringspraktiker. Student i svensk lärarutbildning [Colonial discourses and racialization practices. Student in Swedish teacher training]. In H. Lorentz & B. Bergstedt, (Ed.), Interkulturella perspektiv. Pedagogik i mångkulturella lärandemiljöer. [Inter-cultural perspectives. Pedagogy in multi-cultural teaching environments] (p. 129–160). (2nd ed.). Studentlitteratur AB.

- Berge, O., Angelo. E., Heian M. T. & Emstad, A. B (2019). Kultur + skole = sant. Kunnskapsgrunnlag om den kommunale kulturskolen i Norge [Culture + school = true. Foundation of knowledge about the SMPA in Norway] (489/2019). Kunnskapsdepartementet (Norwegian Ministry of Education and Research). https://www.telemarksforsking.no/publikasjoner/kultur-skole-sant/3487/

- Bhattacharya, K. (2018). Contemplation, imagination, and post-oppositional approaches carving the path of qualitative inquiry. International Review of Qualitative Research, 11(3), 271–285. https://doi.org/10.1525/irqr.2018.11.3.271

- Bozalek, V. & Zembylas, M. (2017) Diffraction or reflection? Sketching the contours of two methodologies in educational research. International Journal of Qualitative Studies in Education, 30(2), 111–127. https://doi.org/10.1080/09518398.2016.1201166

- Brekke, T. & Heldal, J. (2020, September 6). Hvordan verne om akademisk frihet ved norske universiteter [How to protect academic freedom in Norwegian universities]. Aftenposten. https://www.aftenposten.no/meninger/kronikk/i/dOoERq/hvordan-verne-om-akademisk-frihet-ved-norske-universiteter

- Da Silva, D. F. (2007). Toward a global idea of race. University of Minnesota Press.

- DiAngelo, R. (2021). Nice racism: How progressive White people perpetuate racial harm. Allen Lane.

- DiAngelo, R. (2011). White fragility. International Journal of Critical Pedagogy, 3(3), 54–70. https://libjournal.uncg.edu/ijcp/article/view/249

- Dovey, L. (2020). On teaching and being taught: Reflections on decolonising pedagogy. PARSE Intersections, 11. https://parsejournal.com/article/on-teaching-and-being-taught/

- Eriksen, H., Ulrichsen, G. O., & Bayati, Z. (2020). Stones and the destabilisation of safe ethical space. Periskop – Forum for Kunsthistorisk Debat, 2020(24), 156–171. https://tidsskrift.dk/periskop/article/view/126184

- Feyerabend, P. K. (2010). Against method (4th ed.). Verso.

- Frankenberg, R. (1993). White women, race matters. The social construction of Whiteness. University of Minnesota Press.

- Garvey, J. & Ignatiev, N. (1993). Change our name. Race Traitor, 1(1), 126–127. Routledge.

- Gaztambide-Fernández, R., Kraehe, A, M. & Carpenter II, B. S. (2018). The arts as White property: An introduction to race, racism, and the arts in education. In A. M. Kraehe, R. Gaztambide-Fernández, R. & B. S. Carpenter II (Ed.) The Palgrave handbook of race and the arts in education (p. 1–31). Palgrave Macmillan.

- Hansen, M. E., Gjefsen, T. & Kanestrøm Lie, K. (2015). The end of Nordic exceptionalism? Norwegian Church Aid, Finn Church Aid, Dan Church Aid and Church of Sweden. https://www.kirkensnodhjelp.no/globalassets/utviklingskonf-2015/end-of-nordic-exceptionalism.pdf

- Haugsevje, Å. D., Hylland O. M., & Stavrum, S. (2016). Kultur for å delta – når kulturpolitiske ideal skal realiseres i praktisk kulturarbeid [Cultural participation – when cultural policy ideals must be realised in practical cultural work]. The Nordic Journal of Cultural Policy, 19(1), 78–97. https://brandts.dk/wp-content/uploads/2016/10/nkt_2016_01_pdf.pdf

- hooks, B. (1990). Yearning: Race, gender, and cultural politics. South End Press.

- Hovde, S. (2021). Experiences and perceptions of multiculturality, diversity, Whiteness and White privilege in music teacher education in Mid-Norway – contributions to excluding structures. In E. Angelo, J. Knigge, M. Sæther & W. Waagen. P. (Ed.), Higher education as context for music pedagogy research (p. 269–296). Cappelen Damm Akademisk.

- Jakku-Sihvonen, R. & Kuusela, J. (2002). Evaluation of the equal opportunities in the Finnish comprehensive Schools 1998–2001. Evaluation 11/2002. Finnish National Board of Education.

- Josef, N. (2019). Editor’s note. In N. Josef & K. Pellicer (Ed.), Actualise utopia, from dreams to reality – an anthology about racial barriers in the structure of the Nordic arts field (p. 1–9). Arts Council Norway. https://www.kulturradet.no/inkludering/vis/-/publications-for-nordic-dialogues

- Kallelid, M. & Pettrém M. (2020, August 3). Studenter ved Kunsthøgskolen: Vi ser med stor bekymring på skolens videre utvikling [Students at the Academy of Fine Arts: We are watching the further development of the school with great concern] Aftenposten. https://www.aftenposten.no/kultur/i/1n132W/studenter-ved-kunsthoegskolen-vi-ser-med-stor-bekymring-paa-skolens-v

- Kester, G. (2011). The one and the many – contemporary collaborative art in a global context. Duke University Press.

- Kifle, M. (2020, July 8). KHiO-studenter krever «avkolonisering» av pensum [KHiO students demand “decolonisation” of the curriculum]. Aftenposten. https://www.aftenposten.no/kultur/i/e8Agdg/khio-studenter-krever-avkolonisering-av-pensum

- Kulturskolenettverket. (2019, October 1). KIL-Manifesto. Arts Council Norway. https://www.kulturradet.no/documents/10157/323faf05-0c41-4a6a-84ec-7ba2648d39c0

- Kuokkanen, R. (2010). The responsibility of the academy, a call for doing homework, Journal of Curriculum Theorizing 26(3), 61–74. https://journal.jctonline.org/index.php/jct/article/view/262

- Lenz Taguchi, H., & Palmer, A. (2013). A more ‘livable’ school? A diffractive analysis of the performative enactments of girls’ ill-/well-being with(in) school environments. Gender and Education, 25(6), 671–678. https://doi.org/10.1080/09540253.2013.829909

- Lundström, C. & Hübinette, T. (2020). Vit melankoli. En analys av en nation i kris [White melancholy. An analysis of a nation in crisis]. Makadam.

- Lugones, M. (2010). Toward a decolonial feminism. Hypatia, 25(4), 742–75.

- Matias, C. (2016). Feeling White: Whiteness, emotionality, and education. Sense.

- McIntosh, P. (1988). White privilege and male privilege: A personal account of coming to see correspondences through work in women’s studies. Wellesley College, Center for Research on Women.

- Mignolo, W. (2007). Delinking. Cultural Studies, 21(2–3), 449–514. https://doi.org/10.1080/09502380601162647

- Mignolo, W. (2011). Decolonising Western Epistemology/building decolonial epistemologies. In A. M. Isasi-Diaz & E. Mendieta (Ed.), Decolonising epistemologies: Latina/o theology and philosophy (p. 19–43). https://doi.org/10.5422/fordham/9780823241354.003.0002

- Mignolo, W. & Vázquez, R. (2013). Decolonial aesthesis: Colonial wounds/decolonial healings. Social Text Online. https://socialtextjournal.org/periscope_article/decolonial-aesthesis-colonial-woundsdecolonial-healings/

- Mills, C. (2015). Revisionist ontologies (5th ed.) In Blackness visible (p. 97–118). Cornell University Press. https://doi.org/10.7591/9781501702952-006

- Motturi, A. (2007). Etnotism: En essä om mångkultur, tystnad och begäret efter mening [Ethnicism: An essay on multiculturalism, silence and the desire for meaning]. Glänta produktion.

- Norsk kulturskoleråd. (2016). Curriculum framework for Schools of Music and Performing Arts. Norsk Kulturskoleråd https://kulturskoleradet.no/rammeplanseksjonen/planhjelp/plan-pa-flere-sprak

- Norsk kulturskoleråd. (2019). Kulturskolen som inkluderende kraft i lokalsamfunnet (KIL) [NCSMA as an inclusive force in the local community] https://www.kulturskoleradet.no/vi-tilbyr/program-og-prosjekt/kil/ledelse-i-kulturskolen-2

- Prins, B. (1995). The ethics of hybrid subjects: Feminist constructivism according to Donna Haraway. Science, Technology, & Human Values, 20(3), 352–367.

- Quijano, A. (2007). Coloniality and modernity/rationality. Cultural Studies, 21(2–3), 168–178. https://doi.org/10.1080/09502380601164353

- Rankin, C. (2020). Just us: An American conversation. Allen Lane.

- Rønningen, A., Johnsen, H. B., Tillborg, A. D., Jeppsson, C. & Holst, F. (2019). Kunnskapsoversikt over kulturskolerelatert forskning [Evidence overview of NCSMA-related research]. Norsk kulturskoleråd.

- Said, E. (2000). Orientalism. Ordfront.

- Schierup, C. U. & Ålund, A. (2011). The end of Swedish exceptionalism? Citizenship, neoliberalism and the politics of exclusion. Race & Class, 53(1), 45–64. https://doi.org/10.1177/0306396811406780

- Shields, S., & Hamrock, J. (2017). Finding ourselves: A visual duoethnography. Visual Inquiry, 6(3), 347–387. https://doi.org/10.1386/vi.6.3.347_7

- Skovmøller, A. & Danbolt, M. (2020, December 12). Ripple effects. Kunstkritikk. https://kunstkritikk.com/ripple-effects/

- Skolverket. (2019). Läroplan för grundskolan, förskoleklassen och fritidshemmet 2011: reviderad 2019 [Curriculum for compulsory school, preschool class and school-age educare 2011. Revised 2019]. https://www.skolverket.se/getFile?file=4206

- Smith, L. T. (2013). Decolonising methodologies: Research and indigenous peoples. Cram101.

- SOU 2016: 69. (2016). En inkluderande kulturskola på egen grund. Betänkande av kulturskoleutredningen [An inclusive CSMA on its own terms. Thoughts on the CSMA report]. https://www.regeringen.se/contentassets/7738acadd94d40f79fec6d6fa40e4a80/en-nationell-strategi-for-den-kommunala-musik--och-kulturskolan-dir.-201546

- Spivak, G. C. (1988). Can the subaltern speak? In C. Nelson, L. Grossberg (Ed.), Marxism and the interpretation of culture (p. 271–313). Springer.

- Spivak, G. (1994). Responsibility. Boundary 2, 21(3), 19–64. https://doi.org/10.2307/303600

- Spivak, G., Landry, D. & MacLean, G. (1996). The Spivak reader. Routledge.

- Svensson, T. (2020). The congealed heart of Whiteness. On the possibility of decolonial readings [Doctoral dissertation, Gothenburg University]. http://hdl.handle.net/2077/64919

- Vartdal, R. (2019, September). Meiner ytringsfridomen vert knebla i ny handlingsplan [Argues that freedom of expression will be curtailed in a new action plan]. Khrono. https://khrono.no/gundersen-helland-hf-uio/meiner-ytringsfridomen-vert-knebla-i-ny-handlingsplan/405350

- Vertovec, S. (2007). Super-diversity and its implications. Ethnic and Racial Studies, 30(6), 1024–1054. http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/01419870701599465

- Väkevä, L., Westerlund, H., & Ilmola-Sheppard, L. (2017). Social innovations in music education: Creating institutional resilience for increasing social justice. Action, Criticism & Theory for Music Education, 16(3).

- Wekker, G. (2021, January 11–14). White innocence: Race and cherished self-narratives in the Netherlands [Conference presentation abstract]. Colonial/Racial Histories, National Narratives and Transnational Migration 20th NMR conference & 17th ETMU Conference, University of Helsinki, Finland. https://www2.helsinki.fi/sites/default/files/atoms/files/abstract_gloria_wekker.pdf

- Wekker, G. (2016). White innocence: Paradoxes of colonialism and race. Duke University Press.

- Wolukau-Wanambwa. E. (2018). Margaret Trowell’s school of art or how to keep the children’s work really African. In A. M. Kraehe, R. Gaztambide-Fernández, R. & B. S. Carpenter II (Ed.) The Palgrave handbook of race and the arts in education (p. 1–31). Palgrave Macmillan.

Footnotes

- 1 We draw on the official Swedish translation of Community School of Music and Arts in this context and use the term Nordic Community School of Music and Arts (NSCMA).

- 2 Quijano (2007) argues that the colonial matrix of power is a world power system that has colonised knowledge/imagination globally. This process was initiated during the Spanish seizure of land in South America and naturalised by the rise of modernity during the Enlightenment.

- 3 Svensson (2020, p. 34) uses concepts of marked and unmarked racialisation. Marked racialisation is the construction of the non-normative body that usually occurs to non-Whites. Those who are Whitened attain their privilege by it.

- 4 Cf. Barad (2014); Dovey (2020), hooks (1990) Rankin (2020), Shields & Hamrock (2017) for researchers experimenting with the conventional format.

- 5 The concept was central in the project an Inclusive Cultural Sector in the Nordics where CF was established as a reference group. Its objective was to highlight artists and cultural workers with non-Western knowledge and competencies.

- 6 See Eriksen et al. (2020) p. 165, Fig 4.

- 7 Inspired by Bhattacharya’s (2018) use of Anzaldua’s notion on being a Nepantla, whilst moving in and out of multiple worlds without being indoctrinated in any particular one, we certainly are aware of the possible danger of promoting post-qualitative research as something “new” and “better”.

- 8 Safe space is in its conventional mode, aimed at allowing a critical discussion by centring minority voices in settings otherwise dominated by majority perspectives.