Introduction

I don’t think the course would have been anything without the doing. […] To have done everything and to experience what it becomes in the end, that is what has taught me the most. What is a practical subject if you don’t practise it? It is through the experience of practising and the vulnerability of having practised it myself that I have learned the most.

The above quote is from a student who attended the ten-credit university course in performance art, which this article addresses. The quote confirms the pedagogy I attempted for in the course; an embodied and exploratory pedagogy, where learning is produced through experience and in the making (Ellsworth, 2005). An embodied and exploratory pedagogy is in many ways predominate in performance art pedagogy. In this article, I consider how the course exercises initiated by the teacher matter in producing such a pedagogy. The aim of this study is to investigate how exercises matter in producing a performance art pedagogy that can contribute to the continuous development of the field.

The study presents a diffractive analysis of three exercises from the course. In the diffractive analysis the embodied engagement with the research data is informed by my role as a teacher of the course, performance artist and researcher. The theoretical framework of agential realism and new materialism, where the focus is on how material-discursive practice also produces knowledge (Barad, 2003), informs this study. I will investigate how the course exercises can become performative agents. Barad (2007) uses the term performative agents to describe active agents with the capacity to change a situation through intra-action. Agential realism is part of the post-humanistic turn, which has shifted the focus away from the human as the centre of the universe. Barad’s theories are interdisciplinary and developed in relation to quantum physics, poststructuralism, feminism, and queer theories, among others (Juelskjær, 2019).

This study is situated in performance art, a crossover field that explores the boundaries of the live action of bodies, time, and space. Often, the core of performance art involves disrupting boundaries, resisting definitions, asking awkward questions, taking risks, activating the audience, and being in constant development (Goldberg, 1998; Heathfield, 2004). To define performance art succinctly is to dive into an ongoing discussion, ranging from strict definitions to a more open notion of a diverse field in which various manifestations, aesthetics, and methods are accepted (Porkola, 2017, p. 14).

Performance art does not have an institutionally established set of exercises, so it is very much up to the teacher to devise exercises and frame the learning situation. It is also an oft-repeated statement that “performance art cannot be taught”. In an analysis of this statement, Tero Nauha (2017) questions whether the difficulty of teaching performance art stems from it not being considered an art form, but rather a countercultural phenomenon and form of institutional critique. I would take this further and propose that the difficulty of teaching performance art is also related to the various forms performance art can take, relating to another oft-repeated statement that “There are as many ways of doing performance art as there are performance artists”. This leads, again, to the question of how to facilitate a learning situation that allows for all these possibilities.

In the literature on performance art and pedagogy, several studies have focused on exercises (see Gómez-Peña et al., 2011; Howell, 1999; Porkola, 2017). I have not, however, come across studies that focus on both the teacher’s and the students’ perspectives on how exercises are used in performance art education. The present study contributes to the field by exploring how exercises matter in performance art education by examining the topic from diverse perspectives, combining the polyphonic voices of the teacher, students, and the material-discursive environment.

In the course of my research, I have observed that the dramaturgy of teaching reflects dramaturgical approaches that are common in performance art. These dramaturgical approaches often focus on the agency of objects (Lucie, 2020) and having an open dramaturgy that allows for the unexpected (Gladsø et al., 2005). In planning the course, I used the exercises as ‘building bricks’, or as the ‘dramaturgical approach’ of the course. The learning process occurred in relation to the exercises, specifically how the exercises were mediated and what components they consisted of. This is in line with the way in which the planning and execution of the artistic process informs and creates the dramaturgy of a performance. By exploring the exercises used in the course as the main dramaturgical teaching approach, I analyse the effect of the exercises in the learning situation and how this might matter to the future development of performance art. This study investigates the following research question: How can exercises in performance art education matter as a dramaturgical approach in order for them to become active agents in the re-creation of performance art?

The performance art course

The performance art course was a ten-credit course which was a support subject for students doing a bachelor in drama and theatre at UiT – The Arctic University of Norway. The course took place in the spring semester in the second year of the bachelor program and had four gatherings with three days of intensive workshops throughout the semester. A couple of weeks after the last gathering, the students performed their individual performances for a public. Two weeks after this, they had their exams presenting their approved performance project with a follow-up conversation with an examiner. The participants were eleven students from the bachelor program completing the course, and five guest students from contemporary arts in the two first gatherings. The course was held in the locations of the Art Academy in Tromsø, which differed from the theatre room where the other courses in the bachelor program were held. The guest students and the locations strengthened the affiliation performance art has to visual arts, and also made it easier to grasp how performance art differs from theatre. As mentioned earlier, I was the teacher of the course, and I designed the course based on my background as a practicing performance artist and my institutional background of having a master’s degree in Live Art and Performance Studies from the Theatre Academy in Helsinki.

The focus in the course was to give the students practical exercises and a practical introduction to various forms of performance art. In addition to this, there was theory, lectures, viewing of documentation of works, a reading list, unexpected events, discussions, observations, feedback and a compulsory written assignment. The students also did presentations about a chosen performance artist or artist group, such as Kurt Johanessen, Morten Viskum, Yoko Ono, Linda Montano, the vacuum cleaner or Tori Wrånes, to mention a few. The theoretical side of the course was based on performance studies, especially on understanding the concept of performativity and an introduction to the diverse history of performance art. In the first gathering the theme was ‘identity and autobiography’‚ with a focus on place and body, in the second gathering the theme was ‘everyday and art’, with a focus on time and action, in the third gathering the theme was ‘participation’, with a focus on audience and in the fourth gathering the focus was on developing an individual performance, based on own interests.

In planning the course, I used a two-sided dramaturgical approach, considering the dramaturgy of the entire course through the exercises and dramaturgy of each exercise. In this study the focus is on the dramaturgy of the individual exercises. There were many types of exercises, exploring the themes and focuses as described above, where each gathering had between five and twelve exercises, starting from short exercises to more complex and longer exercises.

Intra-action, performative agents, and mattering

Teaching is a complex practice that is interdependent with the entire teaching environment, including the structure, theme, facilities, and practical exercises of the course (Hickey-Moody & Page, 2016; Taguchi, 2011). All the elements are generated and generative in intra-action with one another. The exercises are material-discursive, in intra-action and entangled with the entire teaching environment, and they compose a dramaturgical structure that allows for the unpredictable to happen. According to Barad (2003, 2007), intra-action is an alternative to interaction in which entities are not separated from one another before the interaction takes place. Rather, in intra-action, the borders between the entities are indistinctive and fluid.

Central to agential realism is the concept of how matter matters (Barad, 2003). Materiality has a constitutive power as well as language and humans, and it is an active agent in creating the world. Materiality is not important in and of itself, but it gains meaning through its interface with other phenomena, through intra-action. According to Barad (2003, 2007), the moments in which the intra-action between agents changes something and takes new forms are called agential cuts. The distinct agencies do not precede but rather emerge through their entanglements and intra-actions with other agents. The agent is not a fixed essence but is produced and productive, generated and generative (Barad, 2007).

This way of thinking – that everything matters and can become agents – implies that the course exercises are not merely formulations of exercises. The exercises are also material, objects, places, or time, and they intra-act with the discourse of the course and the students. Similarly, in this article, dramaturgy refers not only to the language of the exercises but includes the dramaturgy of the material, place, time, and actions. In my work as a performance artist, my way of looking at dramaturgy is through performance dramaturgy, which takes in the complexity of all the elements that construct a performance. In site-sensitive performances, for example, the main building element of the performance is the site.

In agential realism, the focus is not on understanding what something is, but rather how it comes into being. The world is being created or becoming through intra-action. The act of being in relation is what creates the future world. The question is not if the materials matter but how the materiality matters. The performative agents are not something that is constant but something created in the process, continuously becoming and being created anew (Juelskjær, 2019). In teaching performance art, we are shaping the future of performance art through our intra-actions, entanglements, and initiatives. As Barad puts it, “The future is radically open at every turn” (Barad, 2003, p. 826).

Performance art, dramaturgy, and pedagogy

Performance art uses diverse dramaturgical strategies and approaches. However, performance art dramaturgy is not exclusively bound to a dramatic text. Rather, it is determined by the artistic process and multiple approaches to how to set things in order. The dominant dramaturgical approach could be, for instance, the site, the audience, the body, the material, or the strategy with which to compose structures and allow for the unpredictable to happen (Gritzner et al., 2009). This relates to agential realism, in which any type of matter can become performative agents. An example of how to compose dramaturgical structures that allow for the unpredictable to happen is described by Lisbeth Bodd, the artistic leader of the performance art group Verdensteateret. Bodd does not want to control what happens in the relationship between image, text, and sound. She would rather let the dramaturgy remain open so that the various components can meet in unexpected ways (Gladsø et al., 2005, p. 149). The theory of agential realism allows for a broad understanding of dramaturgy in which the dramaturgical components or agents can vary by site, material, language, or action. In my artistic practice, I search for agential cuts when the intra-action between various elements transforms the situation or creates a new form (Barad, 2007). To link this concept to pedagogy, these moments could be the moments when learning takes place.

As a teacher, I strive to use an open approach that contributes to my students’ development rather than defining a single truth about the field. This open definition of performance art as a field in constant change establishes a certain premise regarding how to teach the subject and find ways of opening up possibilities within the field. It also situates this study within performative art didactics, an art didactic based on the idea that art is in constant change (Aure, 2013). Elizabeth Ellsworth (2005) argues that pedagogy must be in the making and that the design of mediated learning environments and the embodied experience is essential in facilitating a space of continuing experience. According to Ellsworth, “It must do this so that those who have not participated in its history – in making the knowledges already arrived at – may participate in making its future” (Ellsworth, 2005, p. 166). This is in line with how I, in the present study, investigate how exercises can serve as a tool in performance art education to recreate the potential future of performance art.

Diffractive research methodology

In the present study, I engage in a diffractive analysis, searching for agential cuts in line with Barad’s agential realism, in which I, as a researcher, intra-act and intertwine with the material. In the diffractive analysis, I not only observe but also produce phenomena and knowledge. In a similar way, I not only observe what the students do but also create the knowledge through the intra-action with the students and the material-discursive environment. My knowledge as an artist, teacher, and researcher is produced in the making.

The empirical material for this study includes notes, images, and videos from the course, my prewritten plan for the exercises applied during the course, and interviews conducted with eleven students before and after the course. In the diffractive reading of this material, the data do not represent stable knowledge but elements that intra-act with one another, the theory and with me (Koro-Ljungberg et al., 2017).

In my analysis, I look for moments of diffraction and agential cuts; what the exercises do as agents and how they create possibilities, rather than their meaning (Scott, 2015). The focus is on the material effects of difference and how to study the relationship and co-creation between humans and non-humans. Barad defines it as “accounting for how practices matter” (Barad, 2007, p. 88). Diffraction is a concept borrowed from physics that describes how waves change direction as they pass through openings or around a corner (Henderson, 2020). In the diffractive analysis, I look for moments in which the exercises have the agency to cut and create diffraction. This is a specific intra-action in which an agential cut is enacted. The artist researcher Annette Arlander (2018) uses Barad to argue that it is important for the artist-researcher to “focus on articulating the apparatus used, the specific agential cuts enacted, and especially the marks on the bodies generated” (Arlander, 2018, p. 144). This can change within a specific case. According to Arlander, I must not only acknowledge my subjectivity and entanglement with the object of research as a researcher “but also account for the agential cuts within the phenomena at hand – that is, what is included and what is excluded from mattering” (Arlander, 2018, p. 144).

In my double role as a teacher and researcher, I emphasised to the students that participating in the study was voluntarily. I reported the study to the Norwegian Centre for Research Data (NSD) and followed the Guidelines for Research Ethics in the Social Sciences (The Norwegian National Research Ethics Committees, 2016). All of the students in the performance art course gave their written consent regarding the material, including photos of students and situations, to be used in this study. In addition to this, the students who are identifiable in the pictures approved of such prior to the publication of this article. The interview guide did not contain private issues. It all centred on the teaching and the students’ experience of the exercises. However, performance art requires that the students reflect upon identity-related questions. As a teacher and artist, I know that this can be a highly personal process, and I have, as a researcher, been aware of how I deal with the empirical material in order to not reveal any sensitive information.

Another ethical consideration is whether or not the research is trustworthy when it is based on one’s own practice and embodied knowledge. This question is part of a larger discussion concerning artistic and qualitative research methods, in which the subjective voice provides knowledge about something that can be applied to a wider phenomenon. I consequently avoid basing the research on my opinions and, rather, base it on knowledge and experience obtained through practice in constant discussions with the theoretical framework.

In the following analysis, I focus on three exercises from the performance art course. I have chosen these three exercises by searching for moments when the exercises became agents and produced change. Another guide in making this choice was that I wanted to analyse different kinds of exercises that occurred during different dramaturgical stages in the course. The voices of the students, the material encounters, the images as physical manifestations of the situation, the discourse of the university, and my own experience all have a non-hierarchical relationship in this reading. I analyse these voices with a diffractive reading, and I search for what the exercises consisted of and how they worked as performative agents and matter in producing specific situations.

Marking our bodies

Change clothes with another person in the class

It was a shock to change clothes with another person in our class, to see someone else in my clothes, and to observe how much it affects your identity… I thought I was very casual and relaxed. It was an out-of-my-body experience! Clothes matter a lot. (Student, quote from interview)

On the second day of the course, I asked the students to pair up, leave the room, change clothes with one other, and come back. One by one, the students re-entered the room. From the outside, the change did not seem tremendous. Some clothes are a bit too small or very baggy, and they looked somewhat awkward and different. The atmosphere in the class also changed. The students had a new energy; they were laughing, commenting on one another’s looks, taking pictures, and talked about how their feeling about themselves had changed immediately.

In the classroom, the conversation automatically turned toward the core issues of performance art: what it is that forms our identity and how we perform ourselves in everyday life through, for example, our clothes.

According to philosopher and gender theorist Judith Butler, our identity is constructed through language, gestures, and all types of symbolic signs (Butler, 1988, pp. 519–520). In relation to Barad’s agential realism, in which material also has constitutive power, we can say that clothes are not separate from who we are, but are producing and being produced by a complex network of active and equal agents (Barad, 2003). The embodied understanding of the agency of the material, specifically the clothes, was further confirmed in my interviews with the students.

“Since different agential cuts materialize different phenomena – different marks on bodies – our intra-actions […] contribute to differential mattering of the world” (Barad, 2007, p. 178). The students changed through the act of completing the exercise, and the clothes themselves also changed when different people wore them. The most obvious visual change can be seen in the image of a male and female student. On the right, the male is wearing clothes that are too small for him. He is unable to close his jeans; the shirt is so short that it seems like he has just grown out of it. On the left, the female looks as if she is wearing clothes that would be good to hide in, like the large hoodie. Apart from that, the clothes are not particularly gendered, because the style of the clothes could be worn by both genders.

In this exercise, the materiality of the clothes intra-acted with the self-image of the students, the embodied feeling of wearing different clothes, and the different discursive understandings of what clothes seems proper for one to wear. This relates to the aim of the course – to provide a practical understanding of how to create performance art and participate in the ongoing discussion of what performance art has been, is, and will be.

These intra-actions attune us to the materiality of human and non-human relationships. From a Baradian point of view, the students and the clothes are not separate. Bodies are made of and entangled with the world. We form what we wear, but the clothes also form us and “work” differently when worn by others. Our bodies are marked. This exercise gave the students a personal experience of performance art being about the embodied feeling of a performer going through a transformation. It also address the invisible, how it feels to act as a performance artist, what it means to work with your own identity, and how this is portrayed in the work.

Clothes relate to personal identity, and this exercise queers the sense of student identity as a stable subject. To quote Barad (2014, p. 171): “Diffraction queers binaries and calls out for a rethinking of the notions of identity and difference.” The exercise is an exploration of how we can work against the dichotomies of the identity question in order to explore how we can be many things at once and how we are not the opposite of one another but rather a part of one another. The exercise provides an embodied and materialistic understanding of how identity is performative.

Half of the students I interviewed mentioned this exercise spontaneously. Some of them expressed that this exercise was an eye-opener regarding what it means to perform yourself. At least three students used the act of undressing and dressing as part of their independent work later. The exercise had a slightly shocking effect because the agential cut deliberately destabilized the teaching situation. This destabilization allowed for new possibilities and ways of doing.

Material agency

Try out different actions you can do with paper. Write a list of actions and make a composition in five minutes

I think the exercise with the paper was very good. It made me aware of how there are infinite possibilities in a sheet of paper. And then, when I had cleaned it all up, someone came to kick it, and it transformed once again. (Student, quote from interview)

The intention of the second exercise was to give a short introduction to working with material and time. It was a seemingly “boring” exercise. However, many of the students talked about this exercise, and I recall how the exercise created a flow in the class. Here is a quote from a student about how the experience of doing the exercise was liberating:

It was very nice and fun to play with the paper without having to create meaning. I like that there is no prototype in performance art. Normally, I am interested in subjects like maths and science; I love when there is one right answer, but it was liberating to do this because, sometimes, there is not only one solution. And then, it was not so that you got more credit if you were original. Everyone just did it. I understood that we don’t need to analyse in the act but just be in the situation. Everyone was moving the paper around. Someone was tearing it; others were pealing them. There were so many ways to use the paper. (Student, quote from interview)

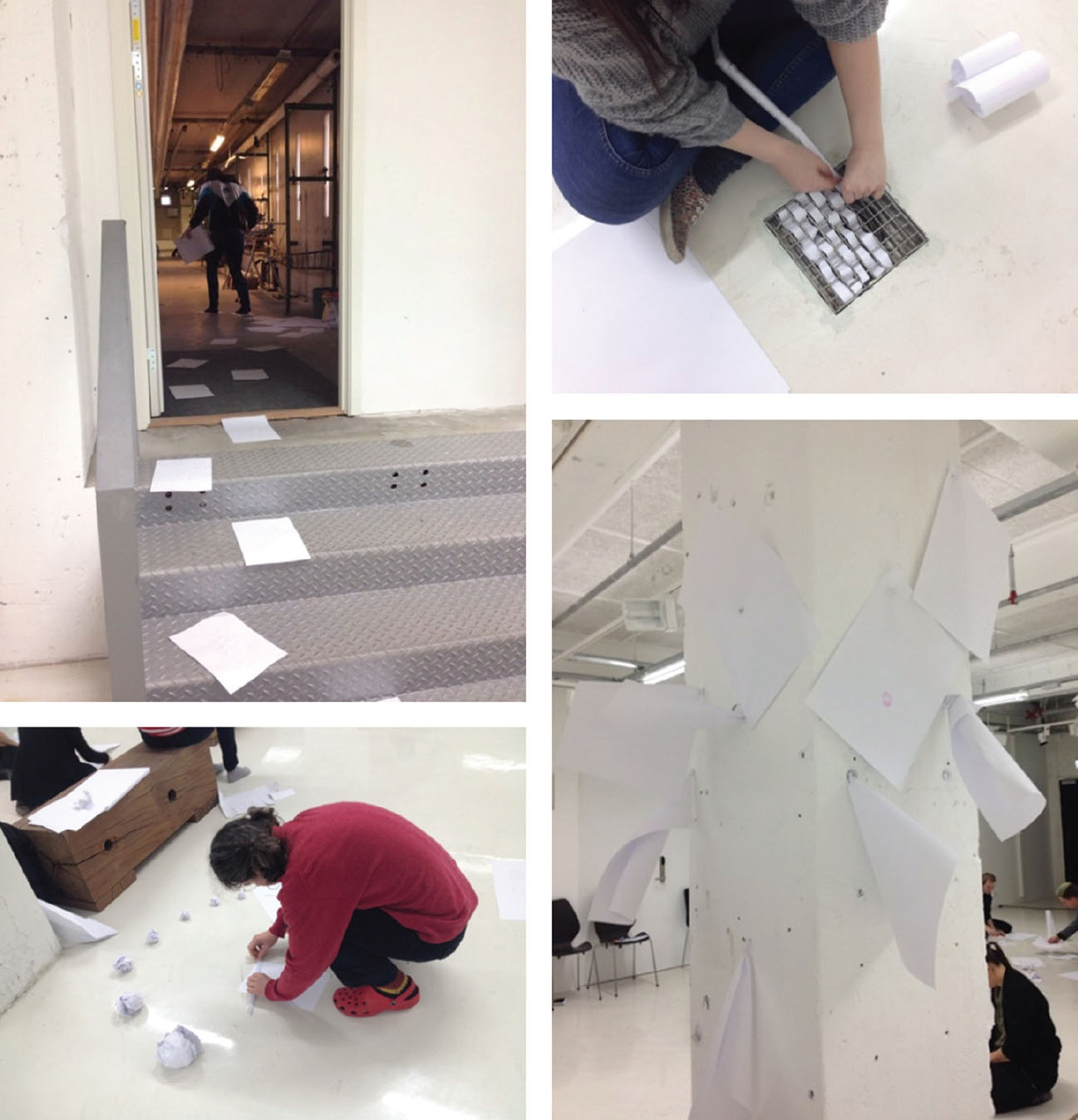

This exercise made it possible for the students to go through many transformations and, as follows, perform actions they could not have imagined. Perhaps because they were told to concentrate on the possibilities of the material, they allowed themselves to go with the flow and be surprised by the potential variations (see Images 3–5). The actions occurred simultaneously, and the actions of others around them inspired them to continue exploring the directions in which this simple exercise could take them.

This exercise mattered by allowing experimentation and exploration. The acts and visual images the students created could not have been planned for without the action and experimentation. The material, the paper, was the driving force and intra-acted with each student differently. The material allowed for indefinite usage. One of the reasons I chose this material was because it was cheap and easily accessible. It also became apparent that using such a common material in new ways was destabilizing the normative use of the material in the discursive environment of the university. The agential cut emerged through intra-actions between each individual student and the paper and their various actions revealed the many possibilities of one agential cut.

The composition part of the exercise, in which students were supposed to create a five-minute composition based on the actions they took, did not turn out to be very interesting. It was far more interesting to observe the images, actions, and multiple answers that were created during the flow of energy, and perhaps, the second part of the exercise was too complicated at that particular moment. The simple exercise, the everyday usage of paper in intra-action with the exploratory approach, led to a deeper understanding for the students on how simple actions can be important in the creation of performance art.

Site matters

Do an action that adds something to a chosen public place

The third exercise can be considered a series of exercises because it consisted of several steps. First, the students were asked to walk with either a blindfold or hearing protection and observe a nearby area. The next day, they were asked to think about an action that could add something new to a place they had noticed during the observation exercise. They presented their ideas to one another in small groups, gave one another feedback, and prepared to perform their ideas. At the end of the day, we watched 15 different actions at different sites and provided immediate feedback.

One important reason this exercise led to an agential cut and created actions and possibilities, was the dramaturgy and timing of the exercise. Because we spent a great deal of time on this exercise, I expected it would lead to new insights. When asked if any of the exercises made a particular impression, one student responded: “What I remember best is when we were standing quietly in the park looking towards the art hall. It was very interesting” (Student, quote from interview). All the students I interviewed talked about this exercise at length, and they confirmed my expectations about how the mediation of this exercise mattered.

The exercise succeeded in balancing the students’ freedom to develop their own ideas with enough structure to support them in encountering new methods and expressions. Furthermore, the way the exercise was mediated emphasised looking for the potential of the various sites, rather than looking back on places or ideas that were not interesting.

For me, it felt like it was the first time we tried out an idea for a performance. It was the second gathering, and then, we were supposed to do something so scary all by ourselves. It was very nice to have the group there, to discuss and get feedback about your ideas. And then, it was inspiring to be able to partake in someone else’s process and to be pulled into all the performances through watching or participating. (Student, quote from interview)

It was essential for the students to have the chance to discuss their ideas in relation to those of others, especially because they were mostly used to working collectively in the creation of new works but now had to defend their own ideas. However, they also experienced the way in which, even as a solo artist, one is still in relation to others.

An important agent in this exercise was the chosen public sites and the fact that we were working outside of designated art spaces. The students expressed how meaningful it was for them to experience how much the site affects the performance. They appreciated the fact that they could really make a difference in the real world. One of the actions most mentioned by the students in the interviews was when everyone in the class stood spread out on a large field, facing toward the local art hall. We stood still for quite some time, until the student who had initiated the action said that it was over. Several mentioned that the performance became interesting when many passers-by reacted to us standing still and looking, and some of them even took pictures of us. This exercise, especially this framing, raised awareness of how much performance art is about choosing a frame to watch from. And also, how the frame chooses the performance and the performers. The site and the audience intra-act with the creation of the performance and can even be the protagonist in the performance.

Some students changed or developed their ideas while they were participating, as the audience, inspired by the performances their fellow students initiated. One student mentioned that, when she was standing in front of the art hall, she came to think that the same thing could be done in front of a more controversial site; the police station. This experiment was very different from the one with the art hall, and it raised awareness of how the site matters for the experience of performing:

I did my exercise outside the police station. I was really happy that nobody came out of the door. First, it was the three of us standing there, and then, more and more people came to watch us from the outside. I hate to get into trouble, but it would have been cool if they came to talk to us. Because we were standing somewhere it is allowed to stand, and it is just a matter of what they feel comfortable with. And then, I feel we were brave that we dared to do this. The police station is a charged building with many secrets. We stood for maybe ten minutes, and it felt like ages. Time feels different when you do something that is uncomfortable. I think it is a matter of time before they would have asked us to leave. (Student, quote from interview)

Another student who asked all her fellow students to cross a road blindfolded changed to a less dangerous crossing area when she recognized how risky it could be to perform in public places. This exercise prompted the students to take risks and try something new in a public place, using the site as the main component to create something.

Discussion

The purpose of this study was to explore how exercises in performance art education may matter as a dramaturgical approach so that they can become active agents in the recreation of performance art. In the diffractive analyses of three specific exercises, I focused on three aspects that intra-acted and mattered within the exercises: the body in the clothes exercise, the materiality in the paper exercise, and the site in the last exercise. These aspects mattered and intra-acted in these chosen exercises, and if I had analysed other exercises, different aspects of those exercises would have come to the fore. The focus, in the analysis, has been on accounting for how materiality matters and what specificity generates (Arlander, 2018, p. 144). These specific intra-actions show that in the planning of the specific exercises, there must be a conscious attempt to include the material-discursive environment. Additionally, in the execution of the exercises, one must allow the material-discursive environment to play and not control it as a teacher.

The dramaturgy of the way in which the exercises were structured influenced the students’ approach to each subsequent exercise. The dominant dramaturgical approach for structuring the course was the exercises, and I wanted to create an open dramaturgy so that the various components could meet in unexpected ways (Gladsø et al., 2005). Each exercise had an exploratory approach and taught the students how to open up to new ways of doing. The unpredictable appeared in the ways in which each student embodied the exercises in their own singular and unrepeatable ways within the given frames. This study suggests that the framing of exercises as the main component in designing a course in performance art, initiates action and give the students opportunities to experience and experiment. Further, it suggests that how the exercises are facilitated matters. The exercises that were analysed as creating change, did not have inherent meanings. Rather, they facilitated the students own exploration of the materiality. The exercises, in intra-action with the surroundings (Barad, 2003, 2007), accommodated the unknown and initiated an event-based experimental pedagogy that involved an unpredictable intra-action between students, material, and teacher (Atkinson, 2011; Garoian, 2014).

The exercises were part of a complex landscape that was interdependent with the context. The way the exercises intra-acted with the students’ past experience was important. In order to adjust and guide the students, the teacher requires her own practical understanding of the field. There is, however, a risk for the teacher to initially suggest how she would have solved an exercise based on her own experience as an artist, which does not necessarily inspire potential variations. This double role of artist and teacher, as well as the double role of being teacher and researcher, has ethical implications. These ethical implications strengthen the argument for keeping performance art and its teaching as a field with multiple methods, aesthetic complexity, and important subjective knowledge. Today, each student will have different understanding of performance art and contribute to the development of the field in multiple, individual ways.

The exercises were encounters that made one see reality in different ways. The exercise that involved changing clothes queered the sense of identity as a stable subject, the exercise with the paper destabilised the normative use of the material in the discursive environment of the university, and the exercise with the sites prompted the students to take risks and be aware of the context. The exercises in intra-action with the material-discursive environment are interlinked with the critique of norms and institutions, which is central in performance art and its pedagogy (Nauha, 2017). It would be interesting for future research to further explore how exercises matter in creating counterculture.

Conclusion

In this article, I have argued that in order to facilitate carefully planned practical exercises, a teacher can potentially initiate the recreation of performance art. The role of the teacher is here to frame an event and design a curriculum in a way that engages and prompts students to redefine what the ever-changing field of performance art can be. This could be referred to as an emancipatory process, in which students take responsibility for their own creativity. In this way, education in performance art can contribute to the development of the field instead of defining truths about the field. In this study, I wanted to highlight how each exercise, also the small ones, matter and can become agents for learning. Through focusing on how exercises matter and intra-act in producing a performance art pedagogy, we see how learning happens in the making (Ellsworth, 2005), and how unpredictability, exploration and experimenting is an important part of this. The practical and tactical exercises are active in themselves and they produce movement, destabilisation, reactions, and actions, which again produce a potential future of performance art.

References

- Arlander, A. (2018). Agential cuts and performance as research. In A. Arlander, B. Barton, M. Dreyer-Lude, & B. Spatz (Eds.), Performance as research: Knowledge, methods, impact (pp. 132–151). Routledge.

- Atkinson, D. (2011). Art, equality and learning: Pedagogies against the state. Sense Publisher.

- Aure, V. (2013). Didaktikk – i spennet mellom klassisk formidling og performativ praksis. INFormation. Nordic Journal of Art and Research, 2(1), 1–24. https://doi.org/10.7577/if.v2i1.611

- Barad, K. (2003). Posthumanist performativity: Toward an understanding of how matter comes to matter. Signs: Journal of Women in Culture and Society, 28(3), 801–831. https://doi.org/10.1086/345321

- Barad, K. (2007). Meeting the universe halfway: Quantum physics and the entanglement of matter and meaning. Duke University Press.

- Barad, K. (2014). Diffracting diffraction: Cutting together-apart. Parallax, 20(3), 168–187. https://doi.org/10.1080/13534645.2014.927623

- Butler, J. (1988). Performative acts and gender constitution: An essay in phenomenology and feminist theory. Theatre Journal, 40(4), 519–531. https://doi.org/10.2307/3207893

- Ellsworth, E. (2005). Places of learning: Media, architecture, pedagogy. Taylor & Francis. https://doi.org/10.4324/9780203020920

- Garoian, C. R. (2014). In “the event” that art and teaching encounter. Studies in Art Education: A Journal of Issues and Research in Art Education, 56(1), 384–396. https://doi.org/10.1080/00393541.2014.11518947

- Gladsø, S., Gjervan, E. K., Hovik, L., & Skagen, A. (2005). Dramaturgi: Forestillinger om teater. Universitetsforlaget.

- Goldberg, R. (1998). Performance: Live art since the 60s. Thames & Hudson.

- Gritzner, K., Primavesi, P., & Roms, H. (2009). On dramaturgy. Performance Research, 14(3), 1–2. https://doi.org/10.1080/13528160903519450

- Gómez-Peña, G., Sifuentes, R., & Roger, R. (2011). Exercises for rebel artists: Radical performance pedagogy. Routledge.

- Heathfield, A. E. (2004). Live art and performance. Routledge.

- Henderson, T. (2020). Vibrations and waves – Lesson 3 – Behavior of waves, reflection, refraction, and diffraction. Physicsclassroom.com. Retrieved 25.08.2020 from https://www.physicsclassroom.com/class/waves/Lesson-3/Reflection,-Refraction,-and-Diffraction

- Hickey-Moody, A., & Page, T. (2016). Arts, pedagogy and cultural resistance: New materialisms. Rowman & Littlefield International.

- Howell, A. (1999). The analysis of performance art: A guide to its theory and practice (Vol. 32). Harwood Academic.

- Juelskjær, M. (2019). At tænke med agential realisme. Nyt fra Samfundsvidenskaberne.

- Lucie, S. (2020). Acting objects: Staging new materialism, posthumanism and the ecocritical crisis in contemporary performance [Ph.D., City University of New York]. CUNY. https://academicworks.cuny.edu/gc_etds/3828/

- Koro-Ljungberg, M., Löytönen, T., & Tesar, M. (Eds.). (2017). Disrupting data in qualitative inquiry. Entanglements with the post-critical and post-anthropocentric. Peter Lang Publishing.

- Nauha, T. (2017). “Performance art can’t be taught”. In P. Porkola (Ed.), Performance artist’s workbook: On teaching and learning performance art – essays and exercises. University of the Arts.

- The Norwegian National Research Ethics Committees. (2016). Guidelines for research ethics in the social sciences, law and humanities. https://www.forskningsetikk.no/ressurser/publikasjoner/guidelines-social-sciences-humanities-law-and-theology/

- Porkola, P. (Ed.). (2017). Performance artist’s workbook. On teaching and learning performance art – Essays and exercises (Vol. 61). University of the Arts Helsinki, Theatre Academy and New Performance Turku.

- Scott, J. (2015). Matter mattering: “Intra-activity” in live media performance. Body, Space and Technology, 14. http://doi.org/10.16995/bst.33

- Taguchi, H. L. (2011). Investigating, learning, participation and becoming in early childhood practices with a relational materialist approach. Global Studies of Childhood, 1(1), 36–50. https://doi.org/10.2304/gsch.2011.1.1.36